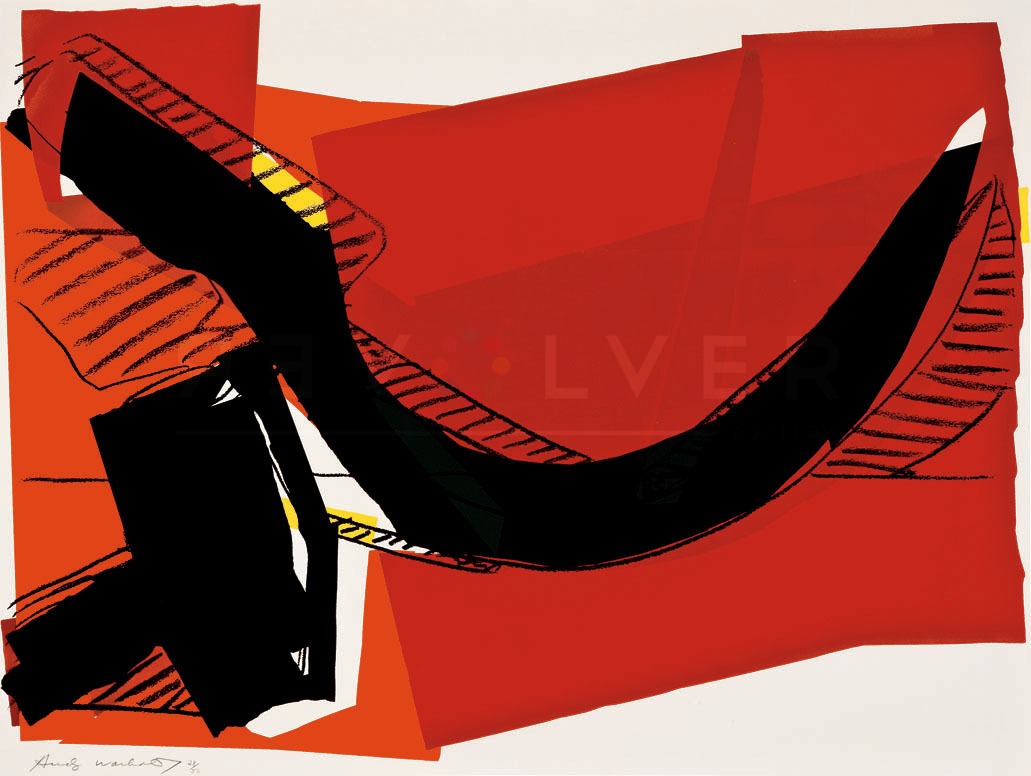

Andy Warhol’s Hammer and Sickle 163 is one of four screenprints from his 1977 Hammer and Sickle portfolio. Warhol created the series in 1976 after a trip to Italy the year prior. There, he noticed the omnipresent hammer and sickle graffiti that symbolized the proletariat union of industrial and agricultural workers. For obvious reasons, the portfolio became somewhat controversial, with some believing the work to be an outright political statement. However, Warhol’s intentions relate to the sensationalism of the iconography (especially during heightened cold war tensions) rather than an affirmation the political ideology inherent to the symbol.

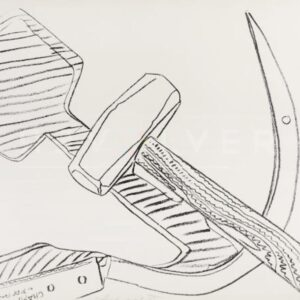

Hammer and Sickle 163, along with other prints from the full series, restructure the infamous symbol while maintaining the basic visual components and meaning of the original. Upon returning from Italy, Warhol asked his assistant Ronnie Cutrone to purchase and photograph a hammer and sickle. Cutrone’s photos formed the basis of the prints, offering an alternate perspective on the universally-recognized symbol.

Rather than placing the hammer and sickle diagonally across each other as depicted in the communist flag, Warhol portrays the tools either alongside each other or only features parts of the objects. He used various shades of red throughout the portfolio, which further alludes to the imagery of the communist flag. In Hammer and Sickle 163, the strong red hues form the background while the tools themselves are blacked-out.

Faced with questions regarding the portfolios political message, Warhol sardonically replied: “we went off to the store and bought a hammer and sickle. Bob (editor of Interview Magazine) has a lawn to cut.” He chose the feared symbol of communism and contrasted it with the lighthearted nature of the Pop Art feel, in order to evoke satire as a personal commentary on the Cold War. Warhol’s bold approach to addressing the political issues of the time showed that he was cognizant of political unrest and the importance of creating a statement through art. Ultimately, Hammer and Sickle 163 shows Warhol’s consistent ability to re-contextualize popular symbols and reimagine them from an aesthetic point of view. This method is one of the basic principals of Pop Art, and Warhol’s firm grasp on this conceptual technique empowers his work—specifically, his ability to expose the blurred line between propaganda and art.

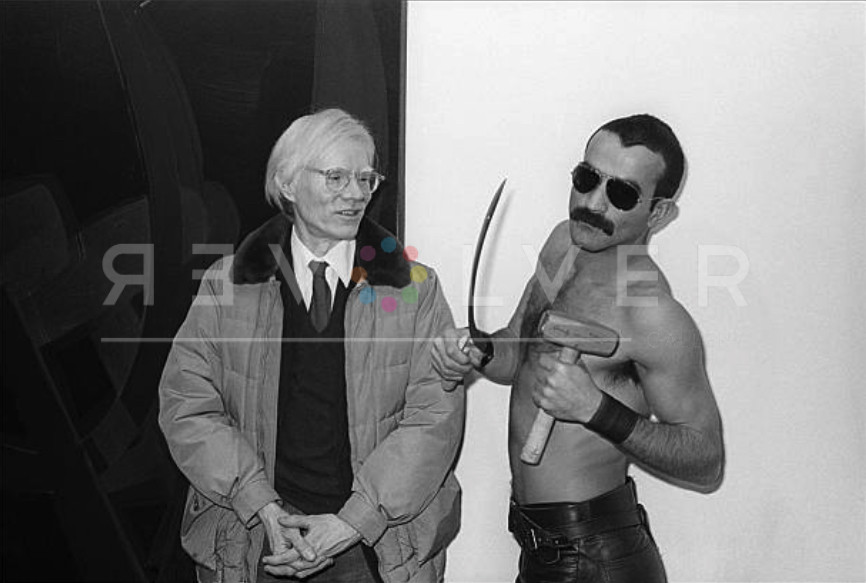

Photo credit: Andy Warhol poses with Victor Hugo, who holds the original hammer and sickle artist used in the works, at the opening of his “Hammer & Sickle” show at the Castelli Gallery, New York, New York, January 11, 1977. Photo by Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images.