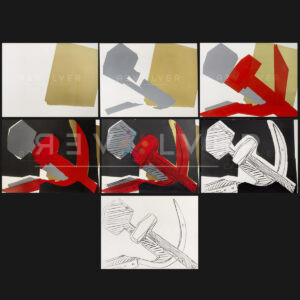

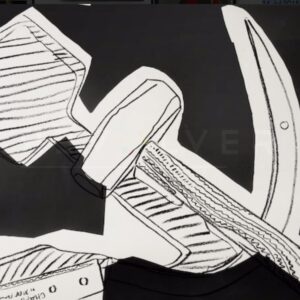

Hammer and Sickle (Special Edition) 169 is a piece created the same year as the original Hammer and Sickle portfolio. The works in the special edition of the portfolio observe the cultural meaning of the symbol, and the global tensions of the Cold War. The special edition series deconstructs the original work’s design and allows for greater interpretation into Warhol’s decision to print the communist symbol.

When Andy Warhol visited Italy in 1976, he saw the communist sigil in graffiti everywhere. The communist emblem, a hammer and sickle criss-crossed with a star above, symbolizes the union of industrial and agricultural workers. Warhol decided to recreate the image when he returned to the states, inspired by it’s ubiquity and persuasive cultural power. He had his assistant Ronnie Cutrone buy a hammer and sickle, which he loosely arranged in a similar fashion and photographed, forming the basis of the screenprints.

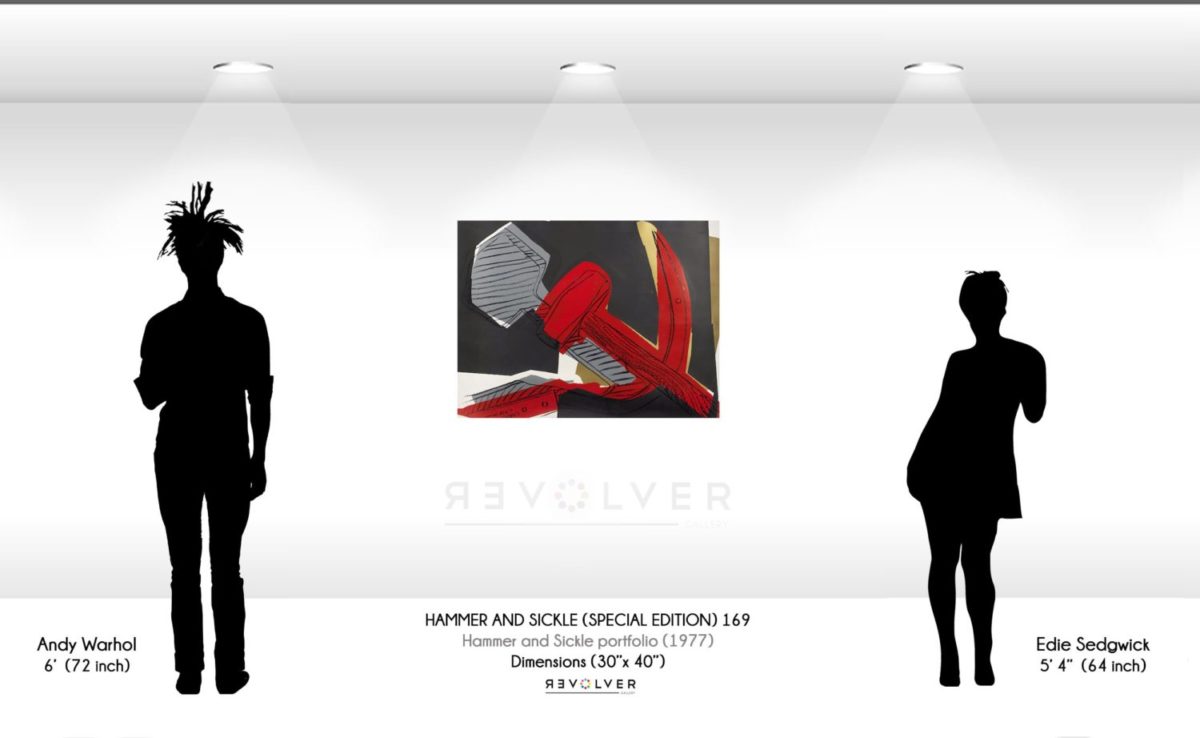

Hammer and Sickle (Special Edition) 169 is a silk screen print with hand drawn elements. It uses lines and directionality to focus on the finer details of the tools, adding realistic earthly texture to the piece. The solid black forms of the background contrast the red of the hammer, but the detail of the wood and metal of the tools allow for better color flow within the composition. This piece emphasizes the individuality of the tools versus their political role they have when placed together; the gray shadows are bigger than the tools themselves and give the appearance that these objects are not innately political symbols, but rather objects placed over one another in the form of an abstract still life.

Unlike the banal gold shape of Hammer and Sickle 165 or limited details of Hammer and Sickle 167, Hammer and Sickle 169 focuses more on function and dimensionality of the tools. Their sketches and directionally create more spatial awareness within the composition and enlivens their function, coming closer to the complete works of the original series.

The communist emblem was greatly feared in America during the Cold War. At one point, it’s supporters (or those accused of supporting it) were blacklisted by Hollywood or imprisoned. The Cold War drew on from the 1940s to the 1980s, and though no battles were fought, the years were full of tension and imminent threats.

Warhol specified that this series had no political leanings, but he did comment once that, “Everybody looks alike and acts alike, and we’re getting more and more that way,” referring to America’s relationship with communism (more accurately, America’s imagination of communism) which raised suspicions about his political tendencies to many.

The abstraction of Hammer and Sickle (Special Edition) 169 reveals that Warhol was not directly alluding to it’s political motif, but rather he was inspired by Italy’s reverence of the motif in public art and it’s social recurrence. By conducting his own version of the symbol, Warhol effectively does the same thing the communism supporters did with graffiti; but, through the efficacy of Pop Art, Warhol detaches the meaning from the symbol, leaving it be admired for its power and relevance, independent of its cultural meaning.

Warhol became admired for his work on this ambivalent series. Through his use of space and articulation of the tools in a representation of the feared symbol, he took a nearly humorous approach to the threatening symbol and reminded us that the tools are neither intrinsically good or bad.

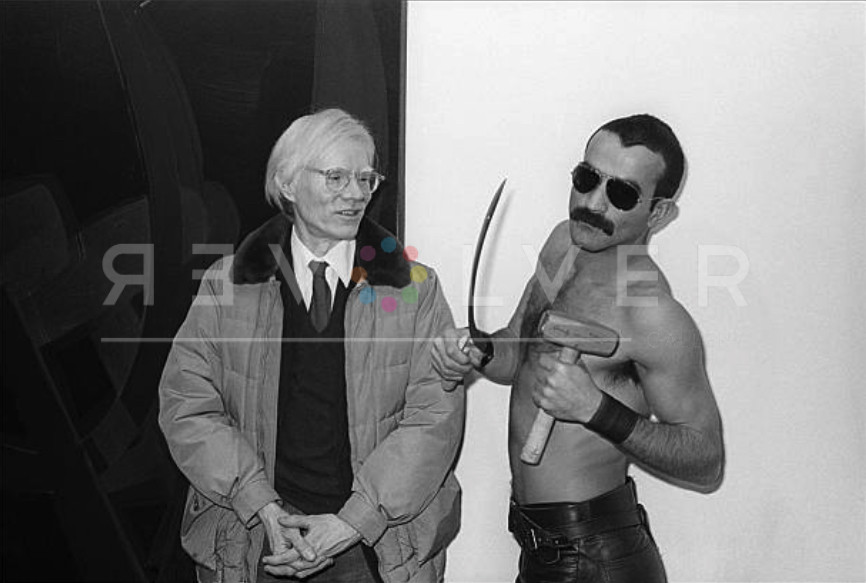

Photo credit: Andy Warhol poses with Victor Hugo, who holds the original hammer and sickle artist used in the works, at the opening of his “Hammer & Sickle” show at the Castelli Gallery, New York, New York, January 11, 1977. Photo by Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images.