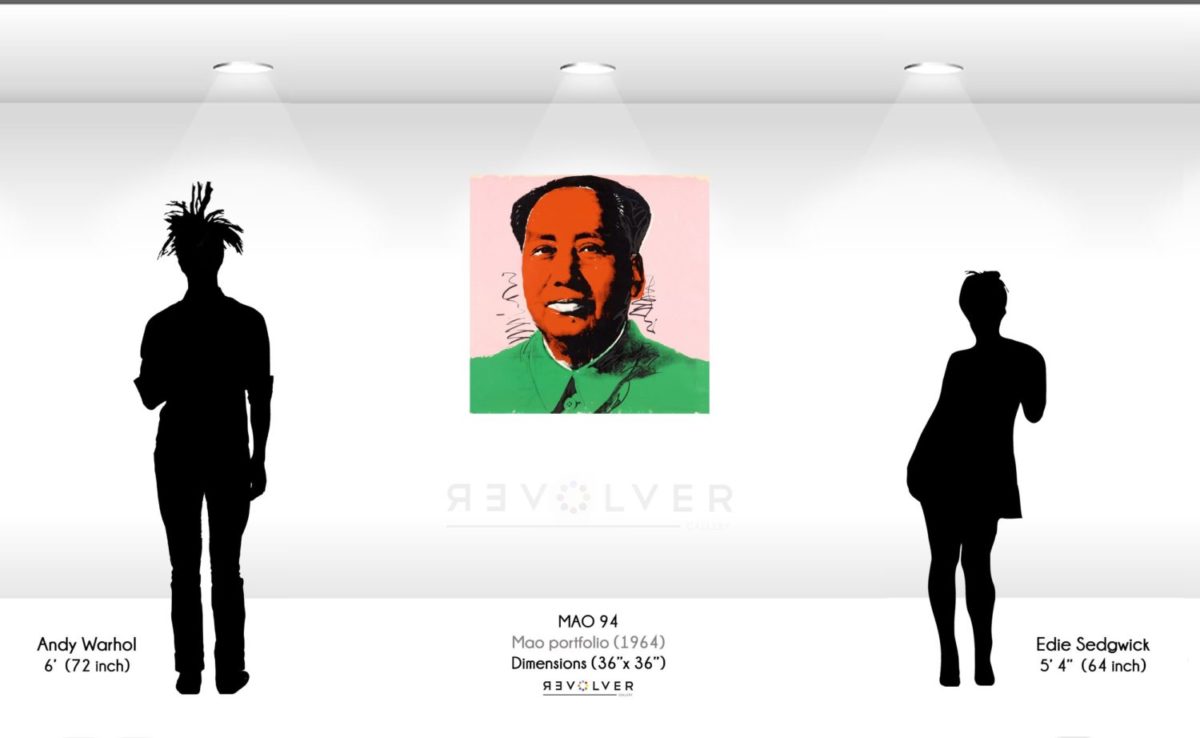

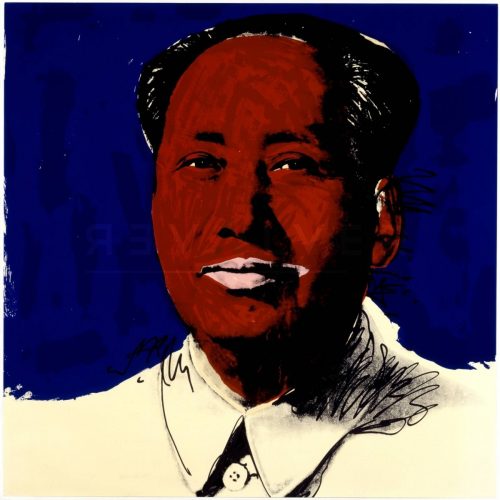

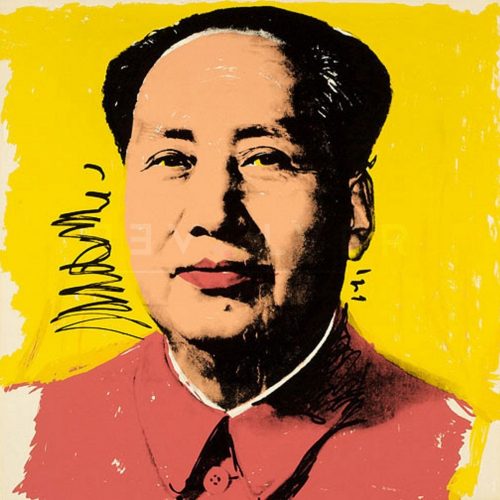

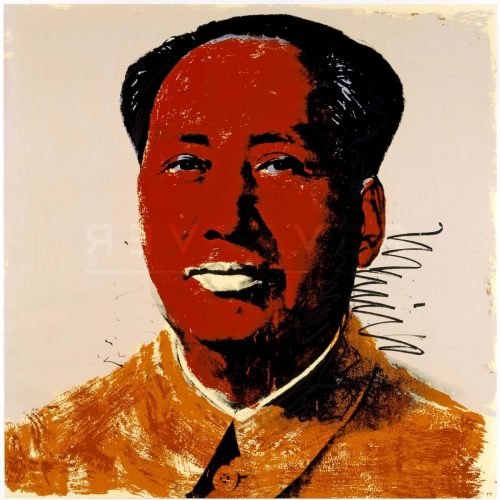

Andy Warhol’s Mao 94 is one of ten screen prints included in his Mao portfolio from 1972. This Mao may be referred to as the red or “pink-red” Mao. As one of his most controversial works of art, Warhol gives the communist leader the Pop-art treatment in this notorious series.

Andy Warhol was fascinated by historical figures, and used images from Alexander the Great to Queen Elizabeth as the bases for his silkscreens. Occasionally, Warhol turned his attention to communist leaders, creating what are some of his most controversial and recognizable pieces. Despite its focus on a leader diametrically opposed to Warhol’s belief that business and capitalism were positive reflections of the human spirit, the Mao series is so quintessentially Warhol that it is often referenced in the same breath as the Campbell’s Soup and Marilyn Monroe series. Mao 94, especially, is an archetypal example of Warhol’s celebration of bright colors, loud contrasts, and obsession with celebrity and great figures.

One of Warhol’s defining traits as an artist was his belief in the symphony of mass production, consumerism, capitalism, and art. Famously, Warhol once said that “being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. During the hippie era people put down the idea of business. They’d say ‘money is bad’ and ‘working is bad.’ But making money is art, and working is art – and good business is the best art”. This sentiment put Warhol at odds with a great number of artists. More importantly, it identified Warhol philosophically with capitalism. Warhol believed that capitalism had the capacity to create good art, and that it rewarded art. This sentiment translated artistically to a focus on consumerism, and a style that took cues from the bright colors of advertisements. It also conjured a method of producing art that followed a factory model of mass-production.

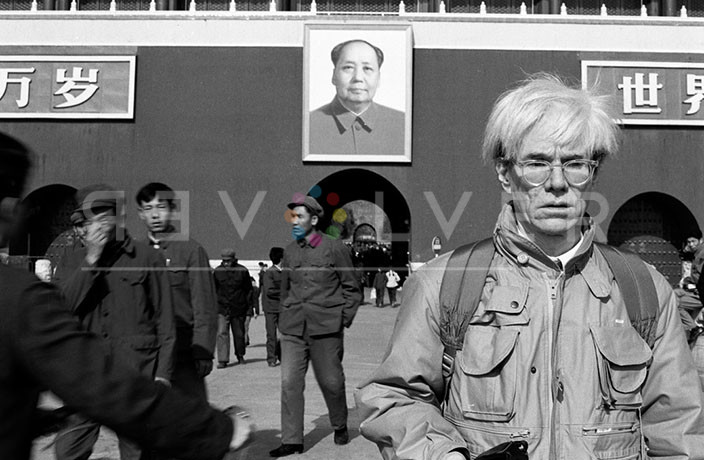

Of course, this celebration of capitalism contradicts the ideology of Mao Zedong, who led the Communist Party of China. But Warhol saw similarities between how he and the Communist Party depicted images. The Communist Party’s glorified portrait of the Chairman paradoxically synergized with Warhol’s colorful celebrations of celebrity. Warhol himself said of the Communist Party’s production of Mao Zedong’s image, “It’s great. It looks like a silkscreen.”

As a result, Mao’s image became a natural fit for Warhol’s artistic depictions of historical figures in creative, consumerist imagery. Though he contradicts the communist ethos, Warhol’s ability to absorb such ethos into his portfolio evidences the relevance enjoyed by his ideology. Moreover, this ideology didn’t end at depictions of consumer goods. Rather, it expanded consumerist imagery to incorporate radically different subjects and ideas.

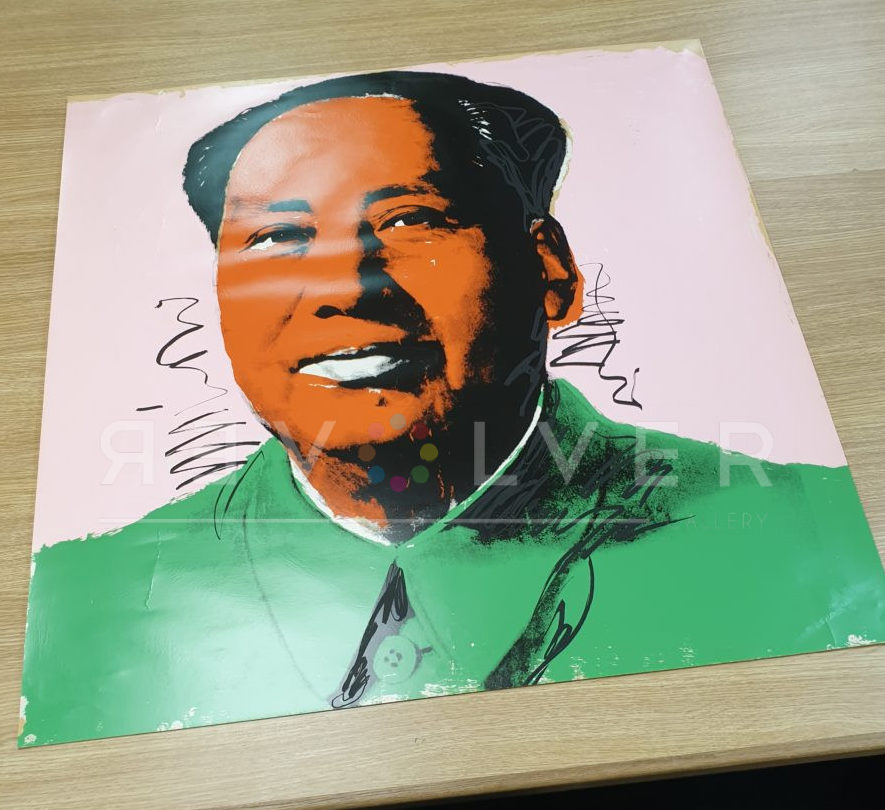

With its bright, vibrant coloration, Mao 94 is one of the most classic Pop-Art prints in the Mao collection. Mao’s neon green coat creates a lively contrast with the bright red covering his face like a layer of make-up. The faded pink background centers our eyes on the bold shading and stark contrasts that illuminate the chairman. Ultimately, we witness the colors and textures that bridge the gap between communist propaganda and Warhol’s playful depictions of celebrities.