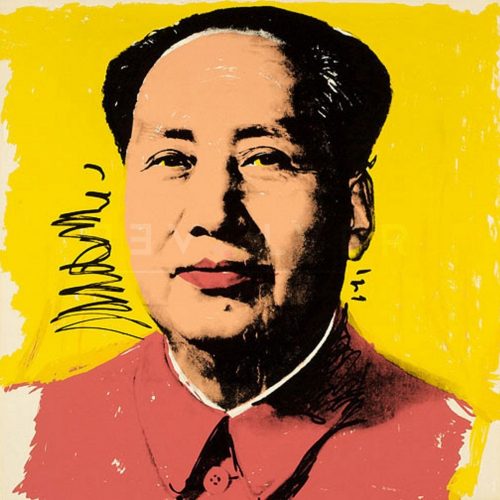

Mao 95 by Andy Warhol is a screenprint from the artist’s Mao (1972)portfolio, one of the artist’s most famous series. This specific version of Mao may be referred to as the “green Mao” in reference to the background, or the “salmon Mao.” Warhol became famous from his portraits of celebrities and consumer objects, although he found inspiration in politics as well. Some of Warhol’s other political imagery includes Alexander the Great, the Lenin prints, and his Jimmy Carter portraits.

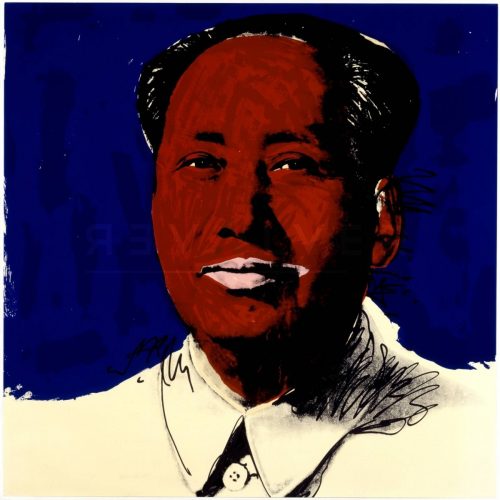

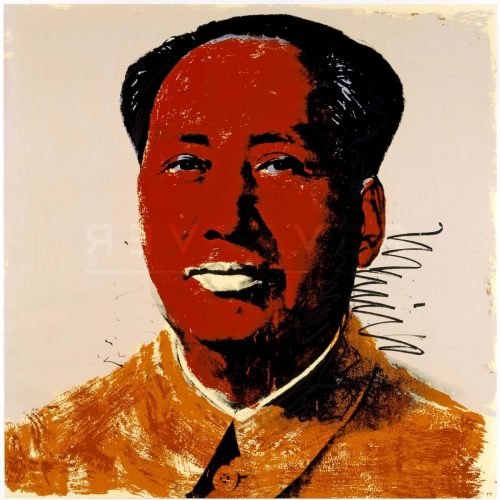

The Mao series, which used Chinese propaganda as the basis for a silkscreen, makes up one of the most notorious series in Andy Warhol’s oeuvre. Warhol’s controversial decision to depict a communist leader is particularly fascinating given his entrepreneurial and individualistic ethos. The culture of Communist China, which shunned individuality and private enterprise, seems antithetical to the consumerist, celebrity-filled culture Warhol espoused. But Warhol, never afraid to employ irony and contradiction, found Communist China fascinating. In a similar manner to his famous celebrity prints, Warhol’s Mao is arguably one of the most important pieces in understanding his philosophy and place in history.

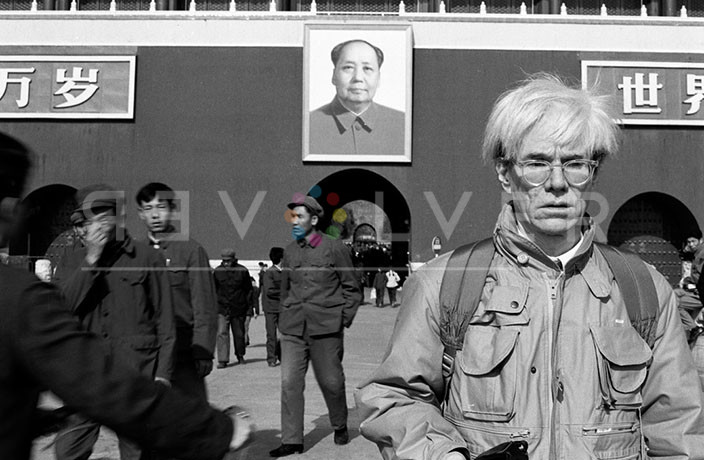

A year before he first started producing silkscreens of Chairman Mao, Andy Warhol said of China, “They don’t believe in creativity. The only picture they ever have is of Mao Zedong. It’s great. It looks like a silkscreen”. One one hand, one might find it surprising that Warhol described the uniformity of imagery in China as “great”. At the same time, Warhol’s observation that Mao’s propaganda was “like a silkscreen” is a recognition of the overlap between two seemingly contradictory philosophies. Like Warhol, the Chinese Communist Party produced many prints of a single subject to glorify its image. In separating the image from its purpose, Warhol has the freedom to engage with it creatively through coloration and manipulation. More importantly, he expresses the irony in the similarity between the representation of an austere anticapitalist leader and the other celebrities and icons Warhol depicts.

The Mao series represents the capacity of Warhol’s philosophy to debase and absorb seemingly contradictory imagery into his body of work. Andy Warhol’s Mao is one of the most striking examples of the idea of “recuperation,” by which radical or anti-capitalist imagery is commodified and re-incorporated into capitalist culture. It presents Warhol’s artistic movement, ultimately, as indomitable. His work becomes so unchallenged that it can reincorporate any counter-ideological imagery as its own.

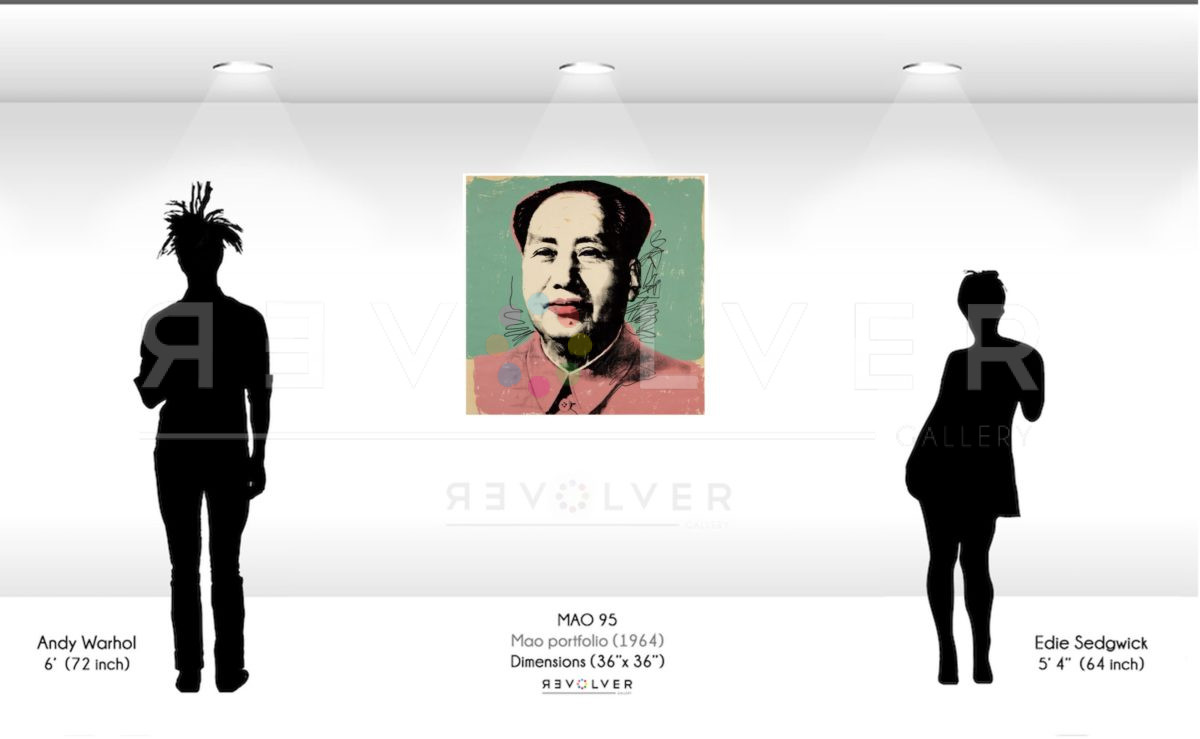

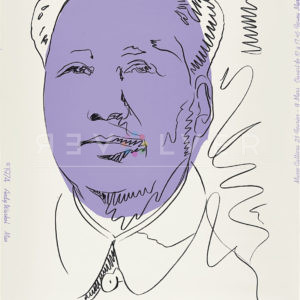

In Mao 95, Warhol colors Chairman Mao’s face with an eye-catching white, which, contrasted with the vibrant red on Mao’s lips, creates the unmistakable appearance of the Chairman in makeup. This is an especially ironic choice, given the Chinese Communist Party’s negative disposition towards individual expression. Warhol colors Mao’s coat and background in unusually subdued pastels–a pinkish red and an engaging yet calm green–which draws the viewer’s eye directly to Mao’s stern face. He also emphasizes Mao’s mole, which may be a reflection of Warhol’s well-known insecurities about his own blemishes. Warhol colors Mao’s eyes a deep purple, giving his stare a penetrating quality, and thus reflecting the intended power of the original propaganda. Ultimately, however, Mao’s portrait now exists in Warhol’s context, and on his terms.