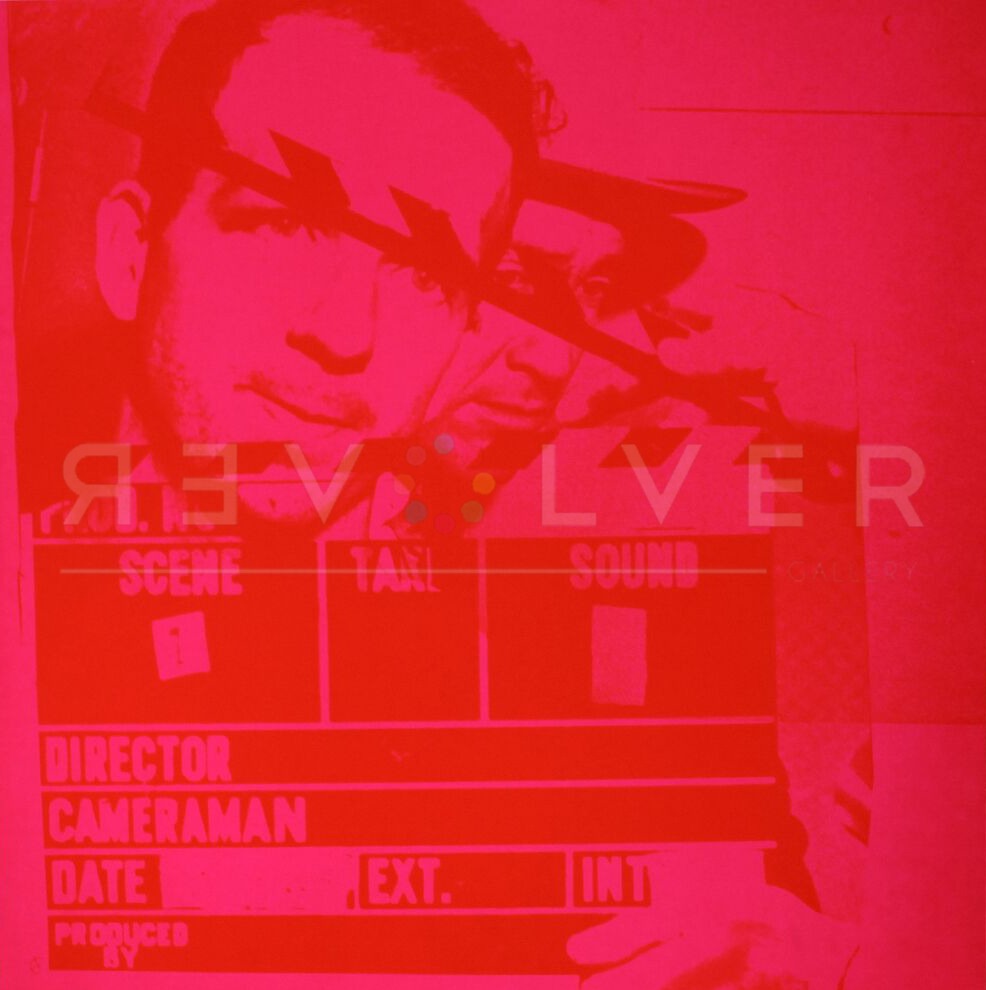

Flash 34 by Andy Warhol is a screenprint from the artist’s Flash series, published in 1968. The portfolio depicts images from the JFK assassination, and the frenzy of media coverage that followed.

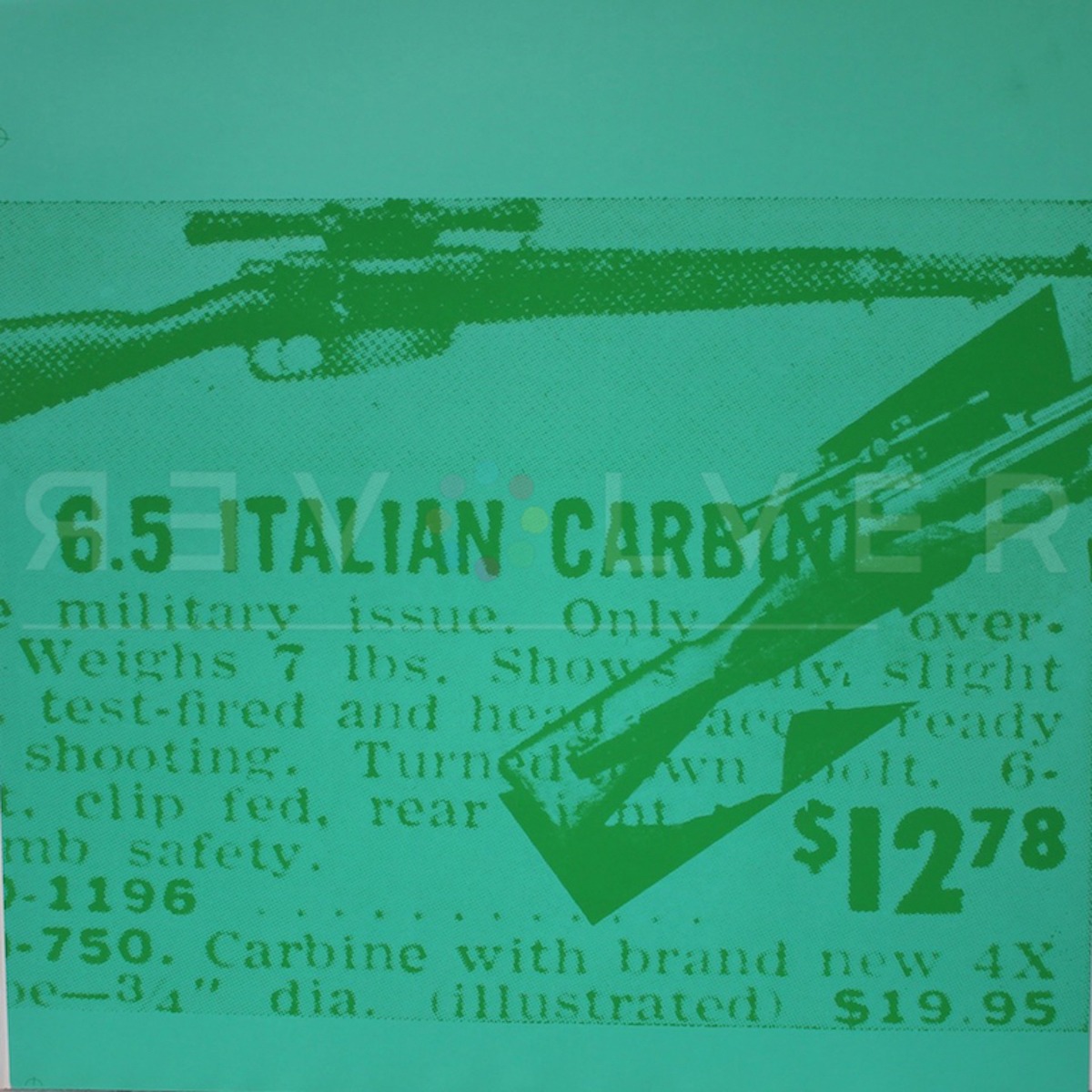

On November 22nd, 1963, President John F Kennedy was shot and killed in Dallas, Texas while riding in a motorcade. A media frenzy ensued for weeks afterward, grainy images flashing over and over again in a dismal cycle of calamity. The assassination of such a beloved president left a permanent scar on the American psyche. As the events unfolded on live television, Warhol watched and absorbed the pandemonium. Five years later, he composed Flash 34. The image is one of eleven prints in Warhol’s series dedicated to the media’s response to the tragedy.

Warhol felt somewhat distanced from the day’s events, but the way the news permeated everything left him deeply disturbed. “I’d been thrilled about having Kennedy as president,” Warhol said. “He was handsome, young, smart, but it didn’t bother me that much that he was dead. What bothered me was the way television and radio were programming everybody to feel so sad. It seemed like no matter how hard you tried, you couldn’t get away from the thing.”

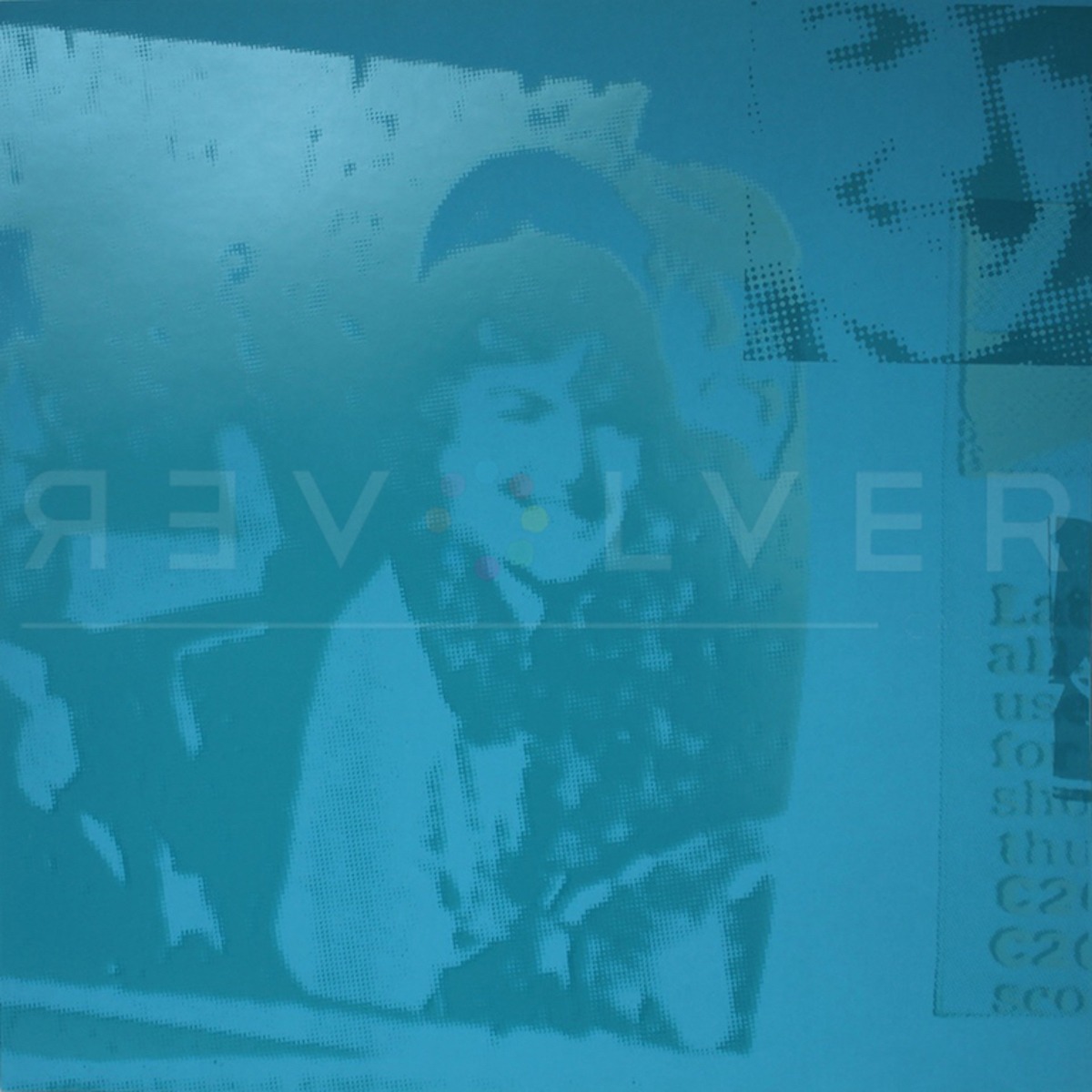

Flash 34 is the only print in the series to showcase first lady Jackie Kennedy Onassis. Warhol places her smiling face front and center while a duplicated close-up of her expression hovers over the upper right-hand corner of the print. Warhol often used repetition to draw extra attention to his overarching ideas. Here, he uses his signature style to convey the media’s replication of the trauma for American audiences. By magnifying Jackie’s smile, Warhol forces the viewer to confront the haunting moments before the murder. The artist washes the scene in shades of blue, giving the image its heavy, somber mood. In addition, the newspaper clipping on the right side of the portrait emphasizes the media circus that surrounded the fallout of JFK’s assassination.

The Flash series was not Warhol’s first exploration into darker themes. Though most know the artist for the intense colors and glamorous celebrity portraits that molded the Pop Art movement, other portfolios like Electric Chair illustrate the depth of Warhol’s curiosity. Without question, the glitz of pop culture enthralled Warhol, but pop culture itself fixated on destruction and tragedy. When anything appealed to the masses on a massive scale, Warhol paid close attention.

Warhol was not the kind of artist to avoid the shadows; instead, he embraced them. For him, this represented a chance to subvert expectations and challenge the art world’s perception of high art. He also wanted to challenge the viewer’s relationship with a murder that played out on live television. In the case of JFK’s assassination, the constant barrage of woeful news coverage appealed to Warhol’s inquisitive nature. He couldn’t help but puzzle over the American media’s infatuation with violence; did catastrophe sell just as well as Campbell’s soup?

Flash 34 is one of the most thought-provoking pieces in Warhol’s series. Throughout the horrific day’s events, the American people had a great deal of compassion for Jackie Kennedy’s suffering. For one fleeting moment she was in the backseat beside her husband on a sunny day, and seconds later she found herself in the middle of a nightmare. Undoubtedly, her smiling portrait taken moments before the killing drives home the heart of the matter. With this print, Warhol captures the upheaval in the days and weeks that followed JFK’s assassination. All the while, he turns a mirror back on the American media, examining the transformative power of its gaze.

Photo credit: Cover of the Chicago Tribune, Friday, November 23, 1965. Courtesy of the Chicago Tribune.