By Aneesa Williams and Mason Rogers

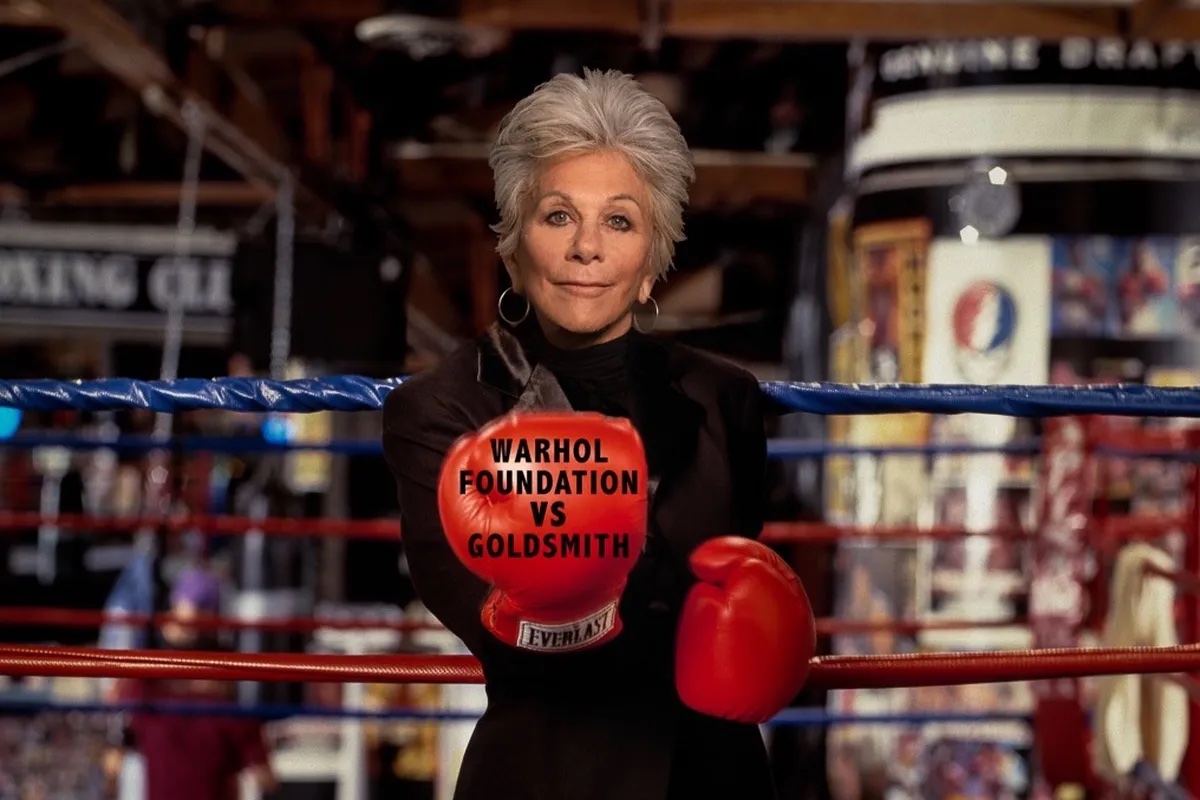

After a long-time legal battle between the Andy Warhol Foundation and Lynn Goldsmith, the case debating the fair use of Andy Warhol’s Prince series has finally been closed. The case, which came to an end on May 18th, had sparked debates about the limits and importance of copyright law amongst artists, entertainment professionals, lawmakers, and anyone concerned with fair use. How much change must be applied to an existing artwork to “transform” it enough to create an original? To what extent can any effort to recreate a work of art be labeled as copyright infringement? A plethora of questions like these have always been relevant, and the distinguishable case between Lynn Goldsmith and the Andy Warhol Foundation brings the conversation to a head with a new ruling that will set new precedent for future disagreements. There’s one answer to the latter: while art is meant to be a vast, enchanting portal of possibilities, the law remains exactly that: the law. In this scenario, the justices ruled 7-2 in favor of Lynn Goldsmith, and here’s why.

Lynn Goldsmith, Andy Warhol, and Prince

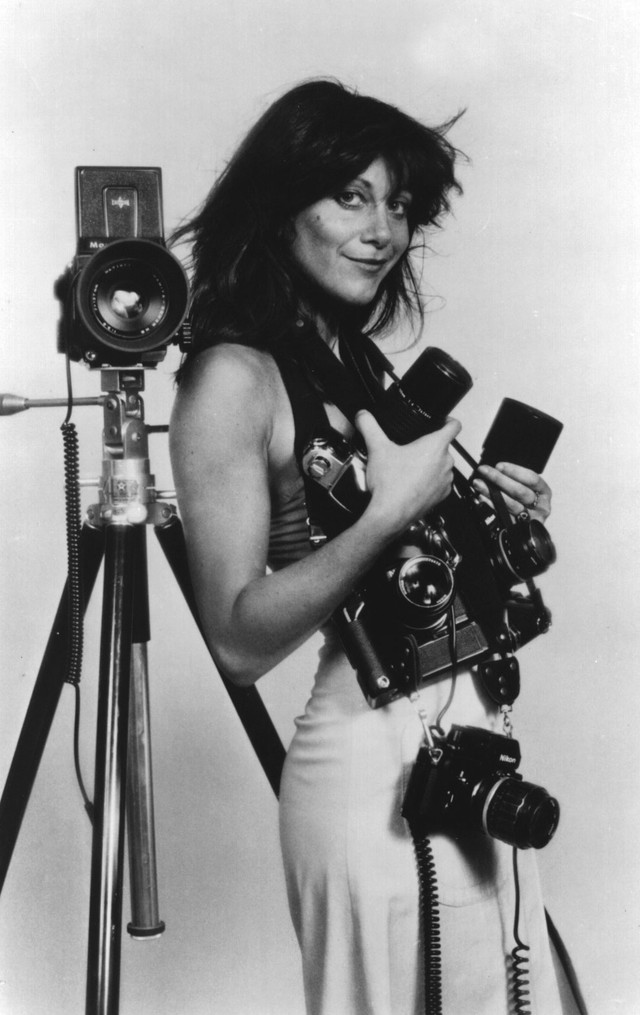

Lynn Goldsmith is an award-winning photographer whose portraits appeared on the covers of Rolling Stone, People, Life, Elle, Time, and more. Lynn has a keen eye that was able to capture the essence of celebrities like Tina Turner, Stevie Nicks, Mick Jagger, Stevie Wonder, and of course, Prince. In 1981, Lynn Goldsmith photographed the great Prince while on assignment for Newsweek, creating an image that, almost 4 decades later, would carry more gravity than she ever thought.

Three years later, in 1984: queue the entrance of Mr. Andy Warhol, a man who had no creative limits and shared his (often controversial) talents with the world. It was in 1984 when Vanity Fair commissioned the artist to create an image of Prince for a magazine spread. By that time, Warhol was remarkably well-known, albeit controversial, and had cemented his legacy as a producer, visual artist, film director, and a leading figure in the pop art movement. He was also a friend and close admirer of Prince himself; Warhol attended many of Prince’s concerts and spent time with him at parties, and Prince’s likeness graced the pages of Warhol’s Interview magazine numerous times throughout the 1980s.

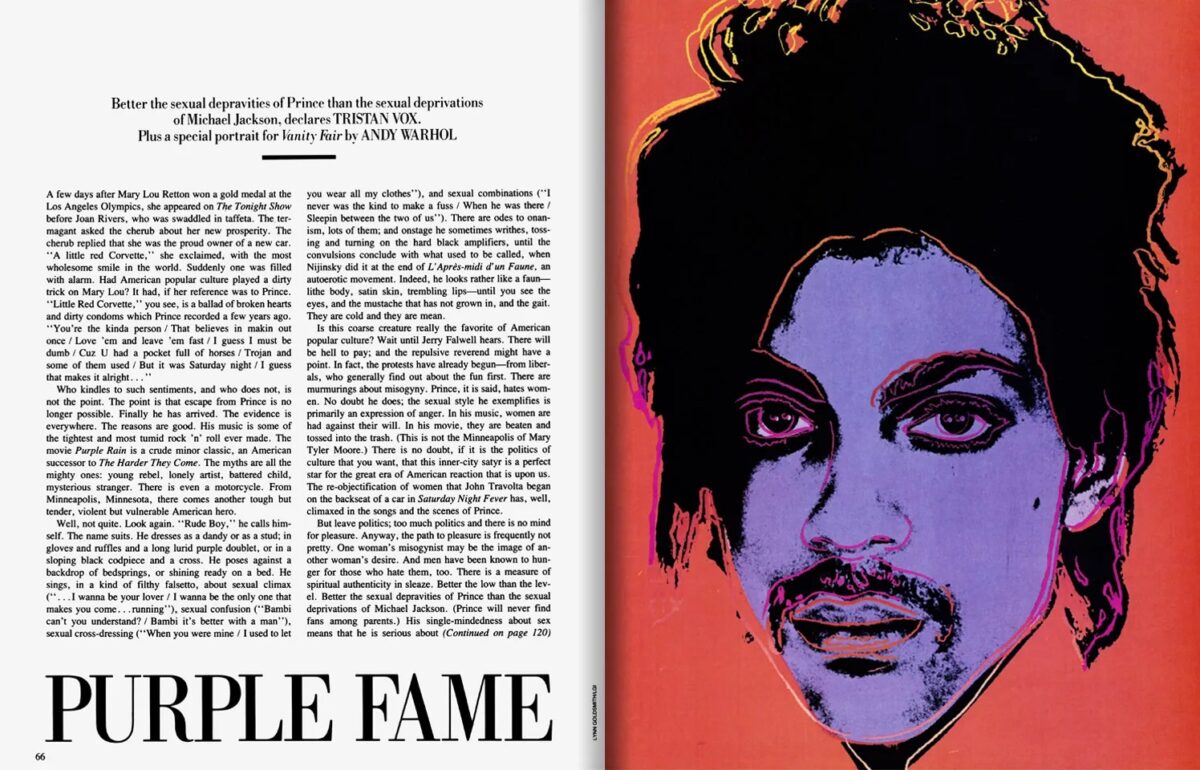

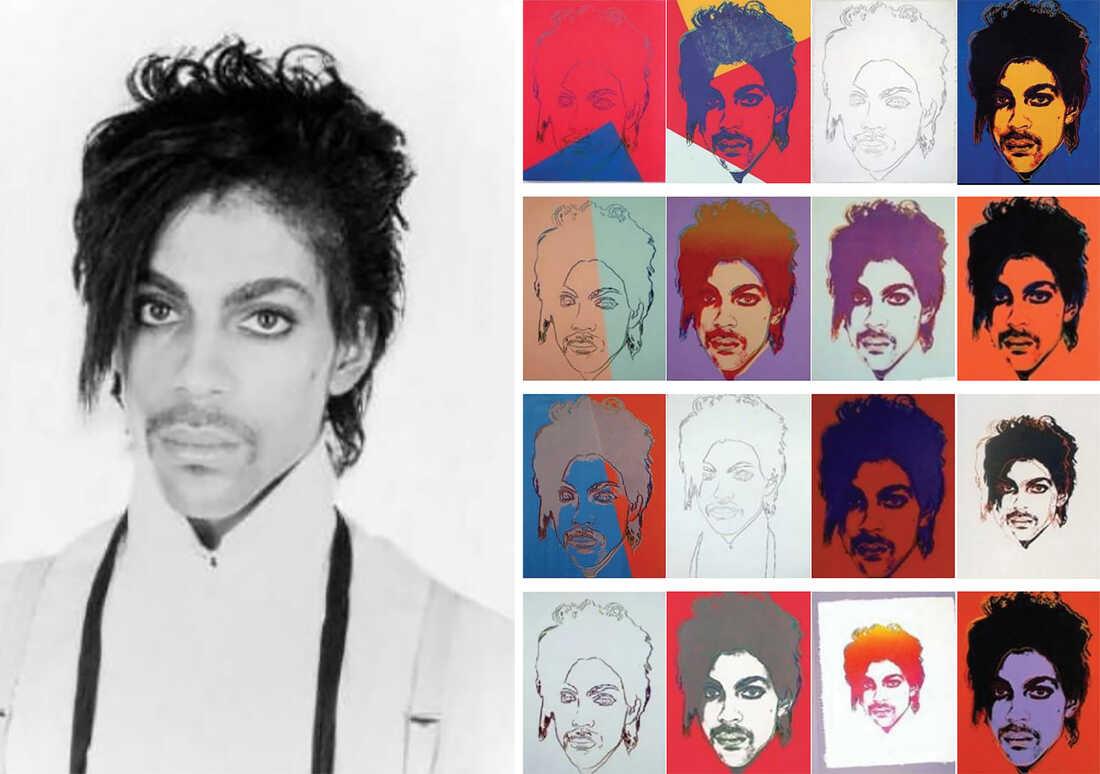

Goldsmith’s photo captured Prince’s piercing expression—his glamorous persona, prominent doe-like eyes, and iconic hairdo—and Vanity Fair wanted Warhol to use her creation for their magazine. Goldsmith permitted a limited license for her Prince photo to be used as “artist reference for an illustration,” and noted specifically that her original photo was to be used “one time only.” Vanity Fair paid Goldsmith $400, and Warhol used her photograph to create a “purple Prince” screenprint that adorned an entire page next to Vanity Fair’s feature in November 1984, appropriately titled “Purple Fame.”

Credit was given where credit was due, Goldsmith was paid and was given credits as the original author of the source photograph in the magazine. Behind the scenes, though, Warhol did more than create a single image for Vanity Fair. Being such a huge fan of the artist, and naturally working within a framework of mechanized serial production, Warhol created a total of 16 Prince artworks (12 paintings on canvas, and four other works on paper) in various colorways, known colloquially as his Prince series. Only one was commissioned, and the rest were forever left in Warhol’s personal creation—that is, until 1987, when Warhol passed away and the Foundation acquired the entirety of the Prince series.

32 Years Later – The Case

The show did not stop there. Many years later, in 2016, following the devastating death of Prince, Vanity Fairs’ parent company Condé Nast asked the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) about recycling the previous 1984 Vanity Fair image to implement in a “special edition” magazine that would honor the life of Prince. Condé Nast learned about the Prince series images, and pursued a license from the AWF to publish.

The major downfall began when Goldsmith became aware of the Foundation’s efforts, realizing that she was completely unaware of the other works in Warhol’s Prince series until that point. Moreover, the AWF had previously sold 12 of Warhol’s Prince artworks to private collectors. Goldsmith informed the AWF of her certainty that they had infringed her copyright, and in response to Goldsmith’s accusations, the Andy Warhol Foundation sued Ms. Goldsmith for, “declaratory judgement of non-infringement, or fair use.” Goldsmith counterclaimed the former for infringement.

The intensely detailed legal language and documentation about the limitations on exclusive rights, and the perceptions of this language, became the center of this debate, one that is now a hallmark for the future ins-and-outs of how and what artists can use in the future.

The District Court took note of the four fair use factors in 17 U.S.C. §107, and allowed the AWF summary judgment on their defense of fair use. In opposition, the Court of Appeals reversed the decision to find that all four fair use factors were in favor of Goldsmith. Lawyer Simon J. Frankel exclaims that the decision, “left uncertain whether museums or collectors may be potentially liable for infringement for displaying or publishing Warhol’s works.” The lone question remained as to whether the first fair use factor, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes,” §107(1) is in overall favor of AWF’s recent licensing to Condé Nast. Goldsmith’s original work is entitled to copyright protection, no matter how iconic, accepted, and easily recognizable Warhol’s work is.

The predominant problem was the first of four factors within the fair use defense under copyright law: “the purpose and character” which references Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph. Subjectively, Warhol’s Prince Series was “transformative”- a term that carries plenty of weight in the discourse of fair-use defense. If this were the case, the Prince series would be categorized under fair use, and not that of copyright infringement. The Andy Warhol Foundation put up a solid argument that the character of Warhol’s silkscreened images was transformative enough to be labeled as an original artwork.

In the court dissent, Justice Elena Kagan, in agreement with Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr,. stated that the verdict “will impede new art and music and literature… It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.”

This ongoing legal debate that originated in 2016 was finally put to an end, but at what expense? What does this court decision mean for the generations of artists to come? Will a shadow be placed on the freedom associated with creating art, or will the decision further reinforce what is appropriate when using inspiration from other artists? Did Warhol alter his piece enough to distinguish it enough from Lynn Goldsmith’s work? Assuming that Andy “ripped off” Goldsmith’s work, and that fair use is an appropriate label for his interaction with her imagery, how will this hinder creativity for artists in the years to come? Perhaps the optimistic few will claim that this decision can only bolster creativity, forcing artists to traverse a more strict concept of “originality” itself. The court gave us our answer, Andy Warhol’s Orange Prince (1984) was not original enough, therefore the work and artist participated in copyright infringement.

This case highlights the importance of artists getting their fair share of meritable and financial credit for the works they’ve offered us. Influential justices like Sonia Sotomayor have noted that in some cases, “borrowing heavily from an original” may be considered fair use, after analyzing Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans. (It’s true. Afterall, Warhol was no stranger to being sued. He got lucky with the Campbell’s Company, who loved that he was appropriating their design).

A Supreme Court case intertwining a musical genius, an astounding artist, and a perceptible photographer is one that stands as a remarkable moment in both art history and the history of copyright law. Although many may feel as though the court ruling should have been determined in a different way, future generations of artists will have no choice but to recognize the ruling as a significant milestone that tightens the reins of fair use. While innumerable arguments were presented to defend the Andy Warhol Foundation, as well as Lynn Goldsmith and her work, the Supreme Court Justices ruled in favor of Lynn Goldsmith on May 18th, 2023. Art, in whatever forms, must continue to allow individuals to exercise creativity, no matter any situation that may be at hand. Andy Warhol was sued multiple times throughout his career, but never acted with much caution considering fair use. Furthermore, Andy was not sued on all occasions for his dismissive nature, and often had the funds to settle any disputes if they did arise. As we see, years after his death, Warhol’s artwork continues to fuel a plethora of important conversations. This time, it happens to be a conversation that will determine artists’ ability to recycle past creations and use the history of visual art as an archeology of ideas and inspirations for their own artworks.

What do you think about the ruling? How do you believe this will shape the world of art in regards to fair use?