Aurora Garrison | November 2017

Few historical figures emerge from the blur of the fast-paced 20th century with single-name recognition and notoriety—Kennedy, Elvis, Nixon, Hitler, Jobs, DiMaggio, Marilyn, Churchill—Warhol. Yet Warhol succeeds where few have gone. Arguably, Warhol’s greatest creation is the icon of himself: aloof, spiked, silver-haired icon, bespectacled and adored today.

Warhol’s art embraces the cultural ambiguities of his times and creates an oeuvre of universal nuance, innuendo and contradiction that teases, delights and befuddles both his contemporaries and the following 21st century audiences.

Already lauded by many as the greatest 20th century artist, Warhol transcends his celebrity status, memorialized in tales of his legendary art studio, The Factory, churning out his prolific silk-screen prints, movies, and photographs, by day; and living an audacious New York nightlife with Studio 54-antics, partying with the social elite, celebrities and stars of music, stage and screen.

Warhol succeeds where others have only attempted and failed: his icon is indelibly stamped on the 1960’s as artist, revolutionary and cult leader of the Pop Art movement.

In the 1970s and 80s, Andy Warhol colorfully and masterfully spun his legendary depictions of celebrities, movie stars, athletes and society figures, while simultaneously mastering the social palate of downtown New York as Warhol created print after print of the cultural icons of his time, all the while constructing his public persona and artistic mystique.

Not only do Warhol’s prints of the cultural icons emanate from the most politically-charged, creative and expressive periods of the 20th century, they also convey a contradictory critique on the themes of popular culture, society, celebrity and consumerism that captivated Warhol’s artistic imagination.

Andy Warhol’s iconic, illustrative depictions of consumerism and celebrities from the 1960s-80s may have had a deeper, more personal meaning for the artist. Warhol dealt with issues surrounding his image from a young age – coming from a poor Pittsburg family, persistent health problems and a perpetual lust for all things beautiful – and felt an insatiable drive to reemerge like a Phoenix in a public persona of his own design and creation.

Warhol lived life on the edge and his life and art were pushed, constantly redefining his personal and public boundaries. So strong was his image of himself as an artist, that he sculpted his own face, undergoing plastic surgery, at a time when the surgical practice was still in its preliminary stage and very experimental. Warhol despised his rounded nose, and sought out cosmetic surgery in 1958 at age 29 in 1958, to re-shape his nose and sharpen his profile. His approach to his life was Pygmalion. And his subject was himself. His face was one of his many canvases.

Warhol’s intense fascination with stardom, immortality through celebrity-status and beauty drew him to iconic figures from the one-of-a-kind Marilyn Monroe to the personalities of the political sphere like Jackie Kennedy. Warhol began producing his Marilyn portraits the day of her death in 1962 and his images of Jackie Kennedy were created just days after the assassination of her husband in 1963. As an artist, he keenly perceived social trends and sorted the extraordinary events and personalities from the ordinary. His art was the filter by which he iconically captured the beautiful. As he famously said, “Pop Art is a way of liking things.”

Indeed, the mesmerizing elements of Warhol’s portraits are that they use outrageous colors and polarizing contrasts that take the art from the surface to iconic and then to sublime.

Warhol’s Marilyn images are some of his most well-known and celebrated works. The piece, Marilyn Monroe 31, is one of a series of ten screen prints he created based on a photo taken by Gene Korman for promotional purposes for her 1953 film Niagara.

Santa Monica, California.

Warhol explains “In August ’62, I started doing silkscreens. I wanted something stronger that gave more of an assembly line effect. With silk screening you pick a photograph, blow it up, transfer it in glue onto silk, and then roll ink across it so the ink goes through the silk but not through the glue. That way you get the same image, slightly different each time. It was all so simple quick and chancy. I was thrilled with it. When Marilyn Monroe happened to die that month, I got the idea to make screens of her beautiful face the first Marilyns.”

Each print from the portfolio is considerably large—bigger than life, so to speak—sized at 36” x 36” with a tight crop of Monroe’s face. Each print is characteristically Warhol—bright blocks of vivid colors that change with each individual print, generating a unique and different feeling for each image. But also, when taken as a whole, showing the depth of the work of art and reflecting the same in the subject herself.

The loud colors bring Marilyn back to life and forever cement her status as a celebrity icon. With the repetitive imagery, Warhol calls attention to her timeless beauty and larger-than-life persona. About repetitions Warhol has said, “The more you look at the same exact thing, the more the meaning goes away, and the better and emptier you feel.”

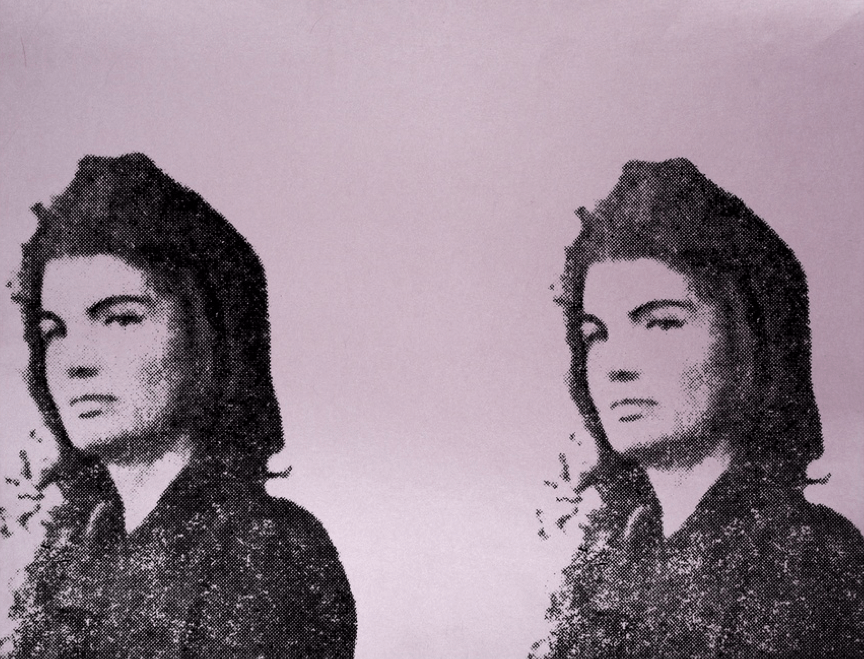

Andy Warhol’s Jaqueline Kennedy II shows a double print of a photograph taken of Jackie during John F. Kennedy’s funeral. Warhol used the images of Jackie, who was world-famous and extremely popular during her husband’s presidency, in a number of different pieces. For Warhol’s generation, the assassination of Kennedy is a key and pivotal point in history. Some have identified Kennedy’s assassination and its aftermath as akin to America losing its innocence in the coming age of violence and cultural upheaval.

In Jaqueline Kennedy II Warhol uses purple paper with the photograph of Jackie in mourning superimposed on the paper, twice. Warhol used a photograph from the December 6, 1963 edition of Life magazine featuring images from President Kennedy’s assassination and funeral.

Taking photographs straight from the popular Life magazine, Warhol draws attention to the media frenzy and the emptiness of the repetitive image. The assassination and Warhol’s following pieces focus on Jackie during the start of the artist’s career, as he was beginning to turn away from his career as a graphic/commercial illustrator to become the most infamous pop artist of his time. The Jacqueline Kennedy series memorialized and iconized the image of Jackie just as the Marilyn prints did, but go beyond celebrity status and becomes a picture of American royalty and loss of innocence. The image immediately conveys the promise of what could have been, then the reality of what was and the resignation as to what was lost.

Santa Monica, California.

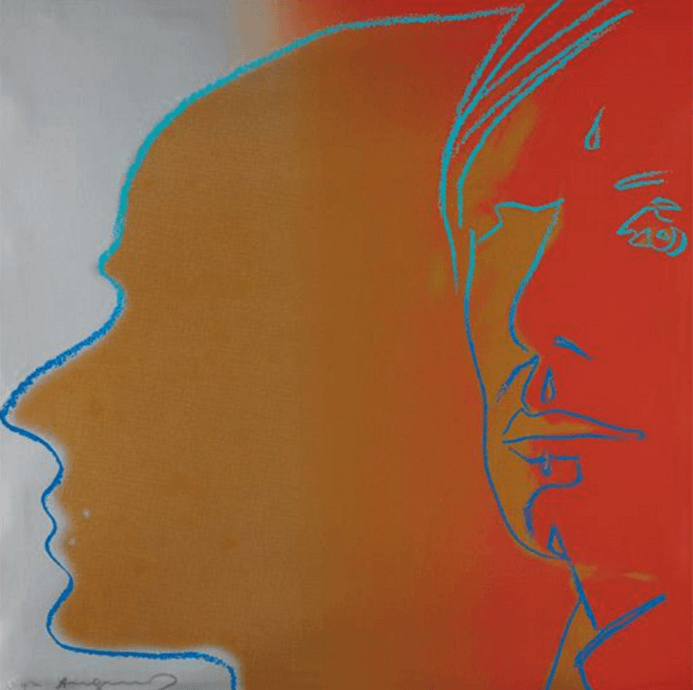

Years before his death in 1987, Warhol produces his Myths series, in which he places himself into a narrative well-known to the American public at the time. In his 1981 Shadow 267, Warhol portrays himself as “The Shadow,” a popular radio crime fighter from the 1930s. The piece is a double portrait, showing Warhol gazing out at the viewer with a Hitchcock-like shadow profile in the background. Through this image, and through his art and his lifestyle, Warhol hoists his icon and achieves his celebrity status with the likes of Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy.

Warhol continues to promote himself and his influential part in American history. The Myths series exemplifies Warhol’s prophetic and forward-thinking nature as the artist places himself amongst popular characters from 1950s television and classic Hollywood films. Displaying fictional American characters, each representing different archetypes of American popular culture, such as Mickey Mouse, The Wicked Witch of the West and Uncle Sam, the artist seems to separate himself from reality.

Warhol sees each of these characters as facets of his personality, and strategically positions himself within the greater narrative of the Myths series to solidify his place in American popular culture. Again, Warhol achieves greatness where few throughout history have even dared to venture.