By Sydney Contreras

With one of the most meticulously documented lives of any artist, it sounds ridiculous to suggest that there is more to Andy Warhol than what we see in one of his Campbell’s Soup cans. In fact, Warhol himself urged the public to look no further than his art, and his body of work is large enough that you could get lost in the archives forever. Maybe that’s what Warhol wanted.

Warhol once said, “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.” This air of honesty is nearly impossible to believe. Warhol pointedly references himself in the third person; this fact alone creates a division between the Andy the public knows and the Andy crafting that exterior. He tells us how to get to know Andy Warhol: the celebrity, artist, public figure, socialite. This subtle move draws a significant line between Warhol and the persona he adopted while in the public eye.

Warhol balanced his candor with secrecy, revealing nearly as much as kept hidden. In interviews, Warhol frequently chose to provide one-word answers to even the trickiest of questions. He cycled between “yes,” “no,” and drawn out pauses or “umms.” When he did choose to answer questions, he often lied. Warhol lied about his age whenever he could—even at the doctor’s office—and although he was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he was known to create fake backstories for himself on a whim.

He volunteered false information regarding his sexuality, too, and the details remain unclear to this day. At age 52, he told a biographer that he was still a virgin—disputing his earlier claim that he had lost his virginity at 25. In an interview from Interview Magazine—a publication that Warhol founded in 1969—one of Warhol’s lovers, John Giorno, poet and star of Warhol’s 1964 film, Sleep, spoke to the contrary, and included explicit details of their time together.

The ephemera of Warhol’s life also supports Giorno’s testimony. In 612 brown boxes, Warhol collected the detritus of his life. Tossing the odds and ends on his desk into these boxes, he created what he called “time capsules.” Among the many artifacts of Warhol’s life collected in these time capsules, biographer Blake Gopnik found evidence to suggest that Warhol was being treated for sexually transmitted diseases at at least two different points in his life.

The muddled stories that Warhol left behind make one thing clear: in his lifetime, the Andy we saw was the one he wanted us to see. His transparency was not honest; he made calculated decisions about how he wanted to present himself to the world. His friends often attested that though he “played dumb” he was far more “analytical, intellectual, and perceptive” than he let on.

His materialistic tendencies meant that his clothing and physical appearance were among the most carefully devised aspects of his public persona. Warhol attempted to cultivate an air of mystery with his style of dress to be sure, but that mystery also contained a painful dimension of insecurity. All his life, Warhol was self-conscious of his looks, and even as he shone in the public eye, he took pains to hide his insecurities.

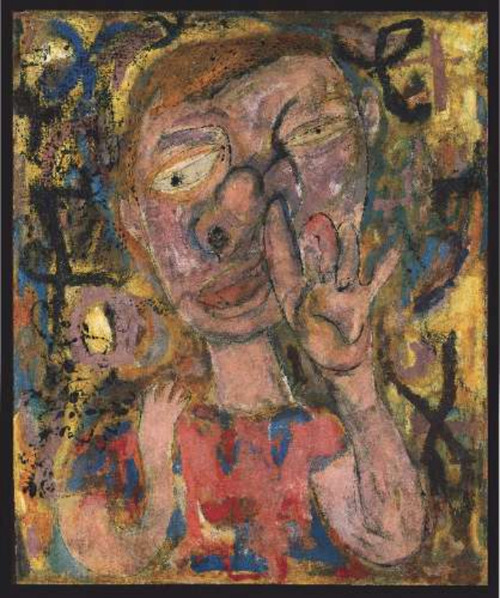

His nose in particular was a source of anguish; he disliked its shape and prominence so much that he got a nose job at the age of 29, which he was ultimately dissatisfied with. In much of his early art from his days at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, Warhol fixated on this perceived imperfection. His 1949 Nose Picker series features a variety of portraits in which he illustrates distorted views of his nose.

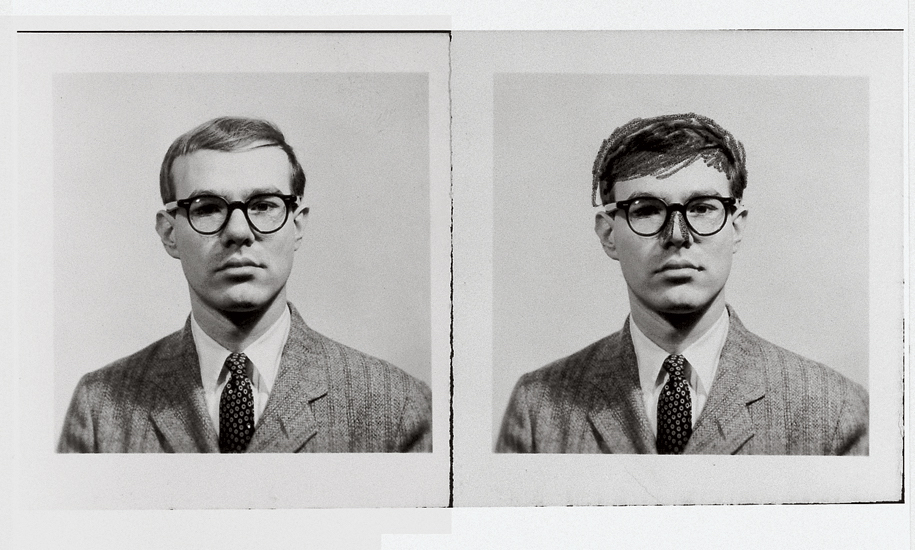

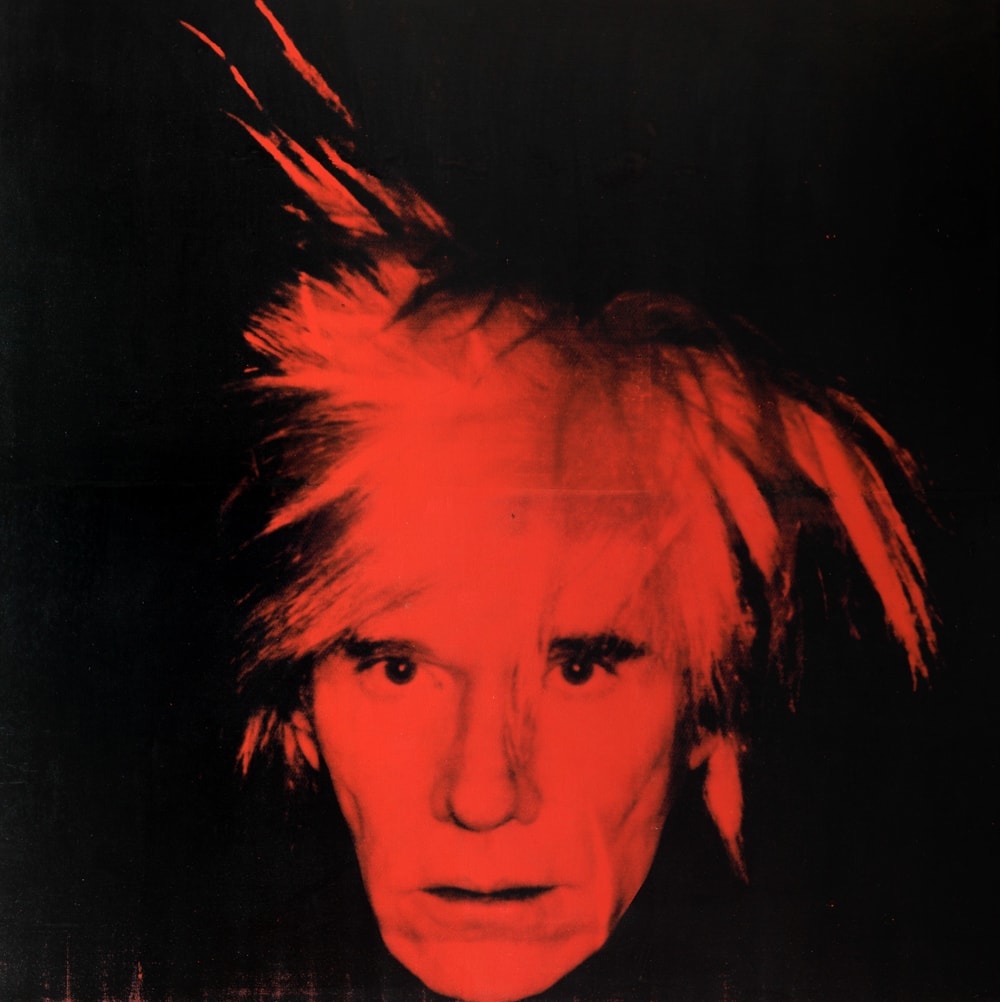

Although Warhol’s wigs were a part of his signature look, this also came from a place of deep insecurity. In his early 20s, Warhol began balding; he wore wigs for the rest of his life in an attempt to hide it. With his early wigs, Warhol attempted to match the synthetic hair to his mousy brown color. With his signature wig—the silver “fright” wig for which he is best known—Warhol instead strays away from reality. The purposefully outlandish look of his silver wig at once contributed to the eccentric persona Warhol had crafted and allowed Warhol to obscure his early balding. Warhol’s 1956 Passport Photograph with Altered Nose also reflects his dissatisfaction with his looks. In this photo, Warhol sketches over his passport photo in pencil, changing the shape of his nose and filling in his receding hairline.

Warhol’s modest wardrobe was another tactic he used to simultaneously hide his perceived imperfections and build upon his persona. Warhol’s perfectly styled clothing included staples such as leather jackets, long sleeves, turtleneck sweaters, and denim pants: all undeniably fashionable, but also chosen for their ability to hide his body.

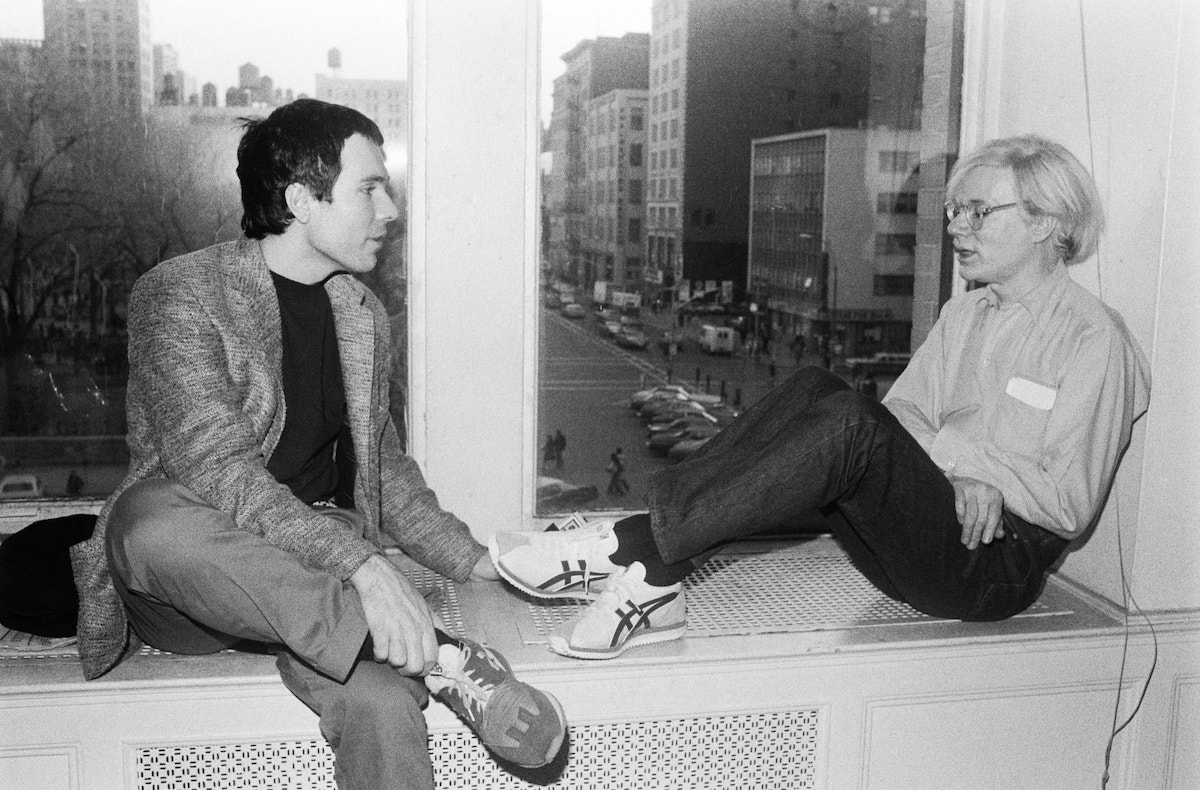

Ex-lover John Giorno, one of the few people to have seen Andy in his entirety, said, “Andy had a beautiful body and all those things that men like, but Andy Warhol’s mind saw his face and body as ugly, and so it negated his beauty.”

So rather than allow himself to be seen as he truly was, Warhol hid himself away in his public persona. Though there are innumerable photographs of Andy Warhol, it is clear that when he allowed himself to be captured on camera, it was a photograph of Warhol the Superstar.

One of Warhol’s most famous self-portraits, his 1986 Self-Portrait (in Fright Wig)illustrates this tendency perfectly. The prints that make up this portfolio all display Warhol as the eccentric, other-worldly man he made himself out to be. His “fright” wig is sticking in a thousand directions; his stare out into the audience is beyond unnerving; above all else, he isolates the portrait to just his head. Though Self-Portrait is certainly a portrait of Andy Warhol, this portrait has an eerie, inorganic feeling; Warhol gives us a portrait of his persona, not himself.

Despite the seemingly unending wealth of information we have about Warhol, there are many things we might never know about the artist; Warhol hid in plain sight throughout his life quite successfully. But perhaps it is the tension between the public and private in Warhol’s work that makes us look a little more closely at it all these years later.