By Taylor Moran

Today, the world of digital art has exploded with online galleries and auctions, cryptocurrency trading, and a plethora of artists, both old and new, creating and selling digital artworks as NFTs (non-fungible tokens). This new era of art has quickly become a global sensation; it has proved itself to be unimaginably lucrative, and a powerful cultural force in the democratization (and general transformation) of art itself. This emergence beckons us to consider the origins of non-physical artwork. If we look closely, we’ll find none other than Andy Warhol at the forefront of it all.

Long before words like cryptocurrency and NFT entered the human lexicon, Andy Warhol learned how to make digital art. The year was 1984, and John Lennon and Yoko Ono had invited a slew of stars to their son Sean’s 9th birthday party. Among the esteemed guests were Keith Haring, Warhol and Steve Jobs, who had gifted Sean a Macintosh for his birthday. While Sean played with the new toy on the floor of his bedroom, Warhol and Haring walked in. It wasn’t long before Warhol was on his hands and knees, trying it out himself.

“There was a kid there setting up the Apple computer that Sean had gotten as a present, the Macintosh model,” Warhol recalled in his diary. “I said that once some man had been calling me a lot wanting to give me one, but that I’d never called him back or something, and then the kid looked up and said, ‘Yeah, that was me. I’m Steve Jobs.’ And he looked so young, like a college

guy. And he told me that he would still send me one now. And then he gave me a lesson on drawing with it.”

After Jobs helped him figure out how to use the mouse (which he first attempted to wave in the air), Warhol became transfixed. Moments later, he gasped in excitement as he made his first digital shape. “Look!” He said, beaming at Keith Haring. “I drew a circle!”

While the Macintosh computer may have seemed like little more than a sensational plaything at the time, Warhol’s interaction with the technology expressed something profound. Throughout his career, Warhol’s ethos relied upon concepts like mass-consumerism and a “factory” style work ethic. When he first met street artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, for instance, Warhol remarked with a twinge of jealousy that he could paint faster. Up-and-coming things always fascinated Warhol, especially if they had the potential to transform modern culture. Throughout his life and career, he longed to be “in the know”, at the forefront of whatever was coming next. As early as 1982, he wrote about the latest technology in his diary: “I went to Crazy Eddie’s and looked at computers, got the Atari game to figure out what all that’s about, and that was exciting.”

Though the possibilities of digital technology intrigued Warhol, the Macintosh had one giant limitation: it wasn’t available in color. The Pop Art movement could not have existed without bold, pulsating colors, so this feature was essential to Warhol. One year later, the artist became brand ambassador for Commodore International, a rival company that boasted color technology. “It’s a $3,000 machine that’s like the Apple thing but can do a hundred times more,” Warhol explained in his diary. As part of his partnership with the company, he created some of the first-ever digital artworks.

“The whole day was spent being nervous and telling myself that if I could just get good at stuff like this then I could make money that way and I wouldn’t have to paint…I thought I was going to pass out. I forced myself to think about the next job I could get if I didn’t. Went along and the drawing came out terrible and I called it ‘a masterpiece.’ It was a real mess. I said I wanted to be Walt Disney and that if I’d had this machine ten years ago, I could have made it.”

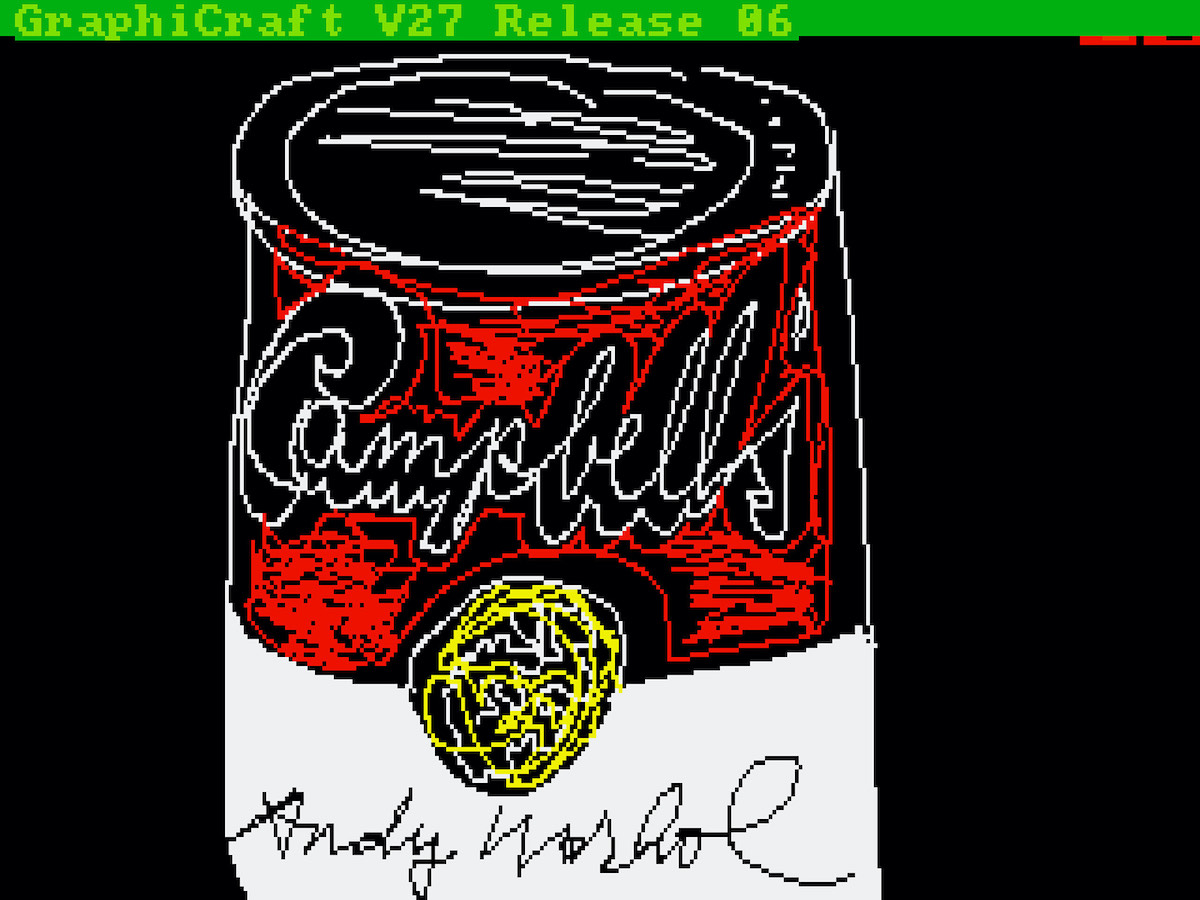

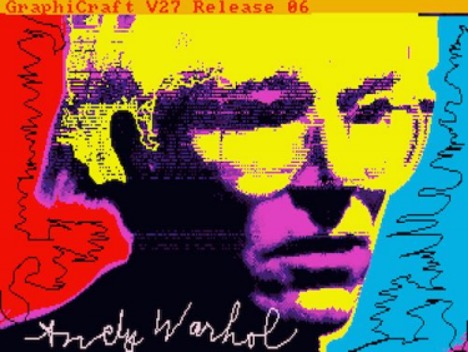

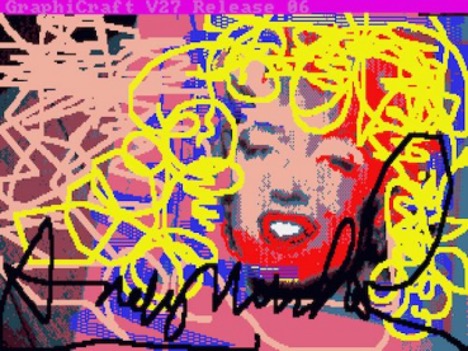

Given the software’s limited capabilities, it is remarkable that the works appear so distinctly Warholian. The artist filled in blocks of color and scribbled line drawings to accentuate his subject’s iconography, just as in his paintings and screenprints. In 2014, a team of archivists led by artist Cory Arcangel unearthed Warhol’s digital paintings. After 25 years, the Andy Warhol Museum made the images available for the first time. One wonders what else Warhol might have accomplished using computers had he lived to see the technology progress.

While Warhol did not put much value in his digital paintings, their significance is profound today. His digital works, whether or not they are the first of their kind, tell a story. Undoubtedly, the images evoke a culture on the brink of transformation. The rise of the Internet and computerized technology shattered boundaries, forever changing the landscape of the art world. Throughout his career, Warhol aimed to make art accessible to all. It is only fitting that he would be somewhere at the helm of this ship in his silver wig and glasses, absorbing its totality.

Warhol’s interaction with the Macintosh signaled a changing of the guard, a shift from one era of art to another. Though he worked with Commodore in 1985, Warhol created a screenprint of the Apple logo that very same year. It would be one of his last works, and a prophetic send-off for Pop, which helped usher in the next generation of revolutionary artists.