By Willie Curry

Intro

An old adage allows for the distinction of a certain artistic faux pas, that is, prioritizing “style over substance.” It is asserted that there’s a dichotomy between whatever meaning a piece of art is “meant” to convey and the means or aesthetics by which that meaning is constructed. However, there are some cases in which this approximate rather than universal heuristic fails to do proper artistic justice. Andy Warhol is such a case. Therefore, for the purposes of this article, a more provocative and therefore, more interesting, stance will be adopted; perhaps, in certain circumstances, style IS substance.

This starting point affords a fuller appreciation of the innovations in production and form present throughout Andy Warhol’s surprisingly eclectic but thematically consistent oeuvre. To chart the evolution of Warhol as an artist is to understand simultaneously the underlying ethos of his entire project and the course of 20th century American popular media. Two themes tend to arise when studying Warhol’s evolution as an artist, namely repetition and efficiency. As such, comparisons to Henry Ford, with his pioneering use of the assembly line, are not so farfetched.

Blotting

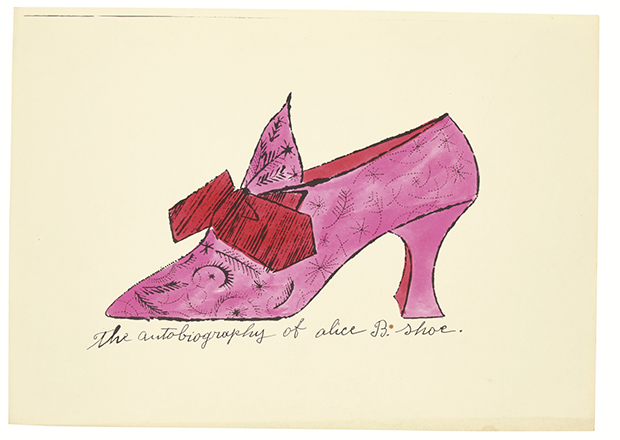

The secret to the special Warhol sauce begins in the early stages of his career, while still a student at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon), where he studied pictorial design. Eminent realist painter, Philip Pearlstein, a fellow CIT alumnus, has suggested that Warhol was heavily influenced by the institution’s course on lithography, lithography being one of the great innovations in printing that allowed for the (relatively) cheap production of images only through the use of a limestone plate, some kind of oil or fat, a series of acid and gum agents, and whatever you wanted to transfer the image onto. This transferring part was particularly important for Warhol, who started to use a “blotted line” or “ink blot” technique for his early illustrations.

This blotted line method consists of first procuring an image – maybe you’re an aficionado of shoes or felines – and tracing it onto another sheet of paper. This traced image is then re-traced in stepwise fashion but with fresh ink, and while the ink is still wet, pressed against a final piece of paper (or whatever medium of choice), blotting the ink in a half-mechanical, half-homemade process. This fulfilled Warhol’s demands of being able to create many copies of the same source image but also being able to do so with a distinct look. This innovative technique is responsible for Warhol’s popularity and success as a commercial illustrator in the 1950s as evidenced by his ads for the I. Miller Shoe Company, work for Glamour magazine and the New York Times, and album covers for the prestigious Blue Note Records. In contradistinction to the above Pearlstein suggestion, Warhol, in his typically blasé and demure fashion, clamed that this use of blotted ink came about partially by accident and partially out of dissatisfaction with his own drawing.

Outside the commercial realm and other methods

Whatever the origin, Warhol would maximize his blotted line output outside of his commercial art illustrations by self-publishing a number of promotional books in collaboration with poet, Ralph Pomeroy, and prominent interior decorator, Suzie Frankfurt, in the early 50s. He would around this time also incorporate the use of handmade rubber stamps to produce easily reproducible shapes such as flowers, possibly to combat the ever-increasing use of photography in advertisements.

Screenprinting and beyond

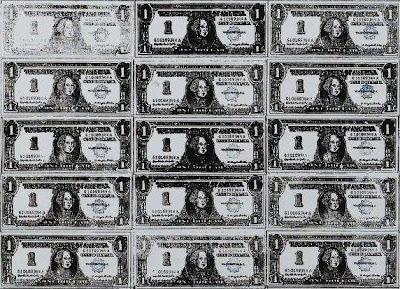

1962 proved to be a revolutionary year for Warhol and the art world at large. Whereas Robert Rauschenberg had previously experimented with transferring photographic imagery onto paper, and artists such as Sylvia Wald and Ben Shahn had similarly experimented with silkscreen printing, no artist had yet to combine these methods in a way like Andy Warhol to eventually create “silkscreen paintings.” Adoption of silkscreen printing, a still relatively new technology that was mostly used in commercial ventures at the time, was the next phase of Warhol’s desire to “become a machine” and further remove marks of the artist such as brush strokes from his work. So, what does screen printing entail?

Ironically, the first step of the process is the one that is the least technical, that is, picking the source image. Warhol had an impressive and incomparable eye for which photos, coming from newspaper headlines, magazine articles, promotional shots for movies, and sometimes stills from movies themselves, to turn into his art. The process then follows, as its name would suggest. On the surface (pun intended!), it’s merely the act of pushing ink with a rubber squeegee through a mesh screen onto a canvas or paper. This mesh screen, interestingly, is covered with a photo-sensitive emulsion, covered with an acetate/transparent version of the source image, and then exposed to light. The light hardens the emulsion and any area not hardened (i.e., not covered by black areas of the transparency) is washed away with a rinse. Ink will only go through the clear portions of the mesh. Warhol’s early forays with the method, in some ways, mirror his blotted line works. His 200 One Dollar Bills from 1962 shows a stunning, machine-like repetition but each bill is distinct from another, resulting from differences in pressure and the amount of ink applied.

Not content to just using the silkscreened images, however, Warhol began to directly paint onto the canvas in high key color palettes prior to screen printing, following the projected contours and negative space of his source images. This resulted in a striking contrast between the dark black hues of the screenprinted image and considerably glitzier splotches and bands of color riding just under certain features of the former. A great early example of this applied is Warhol’s Liz #6 from his Early Colored Liz series, in which a promo image of actress Elizabeth Taylor from her recent film, Butterfield 8, is ensconced in a bright red background, sporting equally red lips, and teal eyeshadow. This combination of acrylic and enamel painting with screenprinted images externally sourced or sourced from photographs by the artist himself or an assistant would become Warhol’s signature method of production as he became more comfortable and assured with it.

Later techniques

Two special series of works should be mentioned before finishing up; one such series is Diamond Dust Shoes from 1980. Warhol (and assistant Ronnie Cutrone) took pictures of shoes obtained from superstar fashion designer, Halston, and gave them the above Warholian screenprinting treatment…. with a twist. The canvases were sprinkled with diamond dust – despite its name, it’s usually comprised of glass or non-gemstone grade diamond analogs – to give the pieces a shiny, glittering appearance, perhaps reminiscent of the gloss the shoes would have in real life. This method was appropriated from Warhol’s master printer at the time, Rupert Jasen Smith, and is a “coming full circle”, returning to the subject matter of shoes which was so crucial to the formation of Warhol’s blotted line technique and therefore, the first major steps in his innovation as an artist.

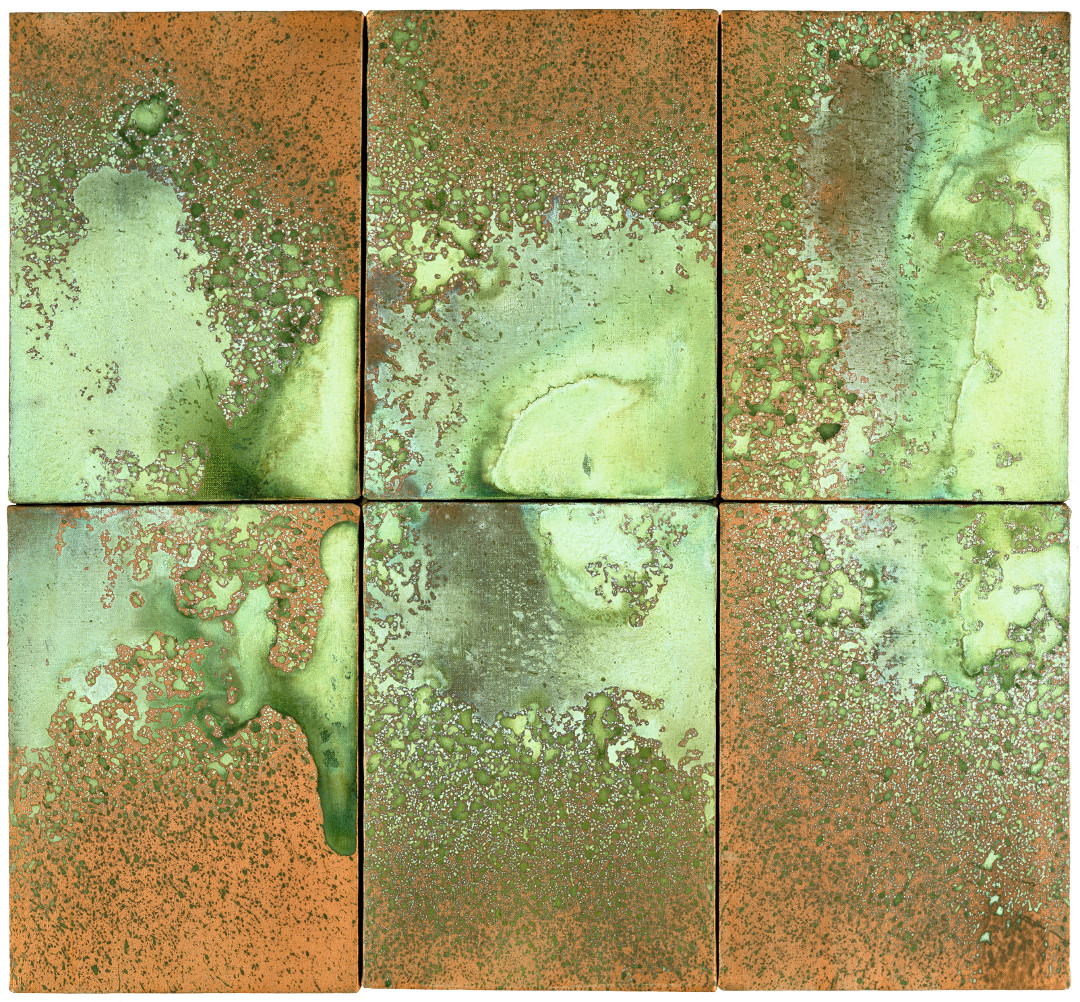

Secondly, it’s worth noting his Oxidation series, completed in 1978. With this rather unorthodox portfolio, Warhol applied a mixture of metallic powder, acrylic medium, and water to canvases he then exposed to urine (from Halston associate, Victor Hugo, and Ronnie Cutrone, among others), essentially oxidizing the surfaces. The result is quite mesmerizing; lavish, coppered and gilded surfaces surround amorphous clouds of jade and dark rust. This approach is admittedly an anomaly in Warhol’s catalogue of work but represents his increasing interest in abstraction throughout the later 70s and 80s.

Outro

We can end here, having explored the trajectory of Andy Warhol’s meta-project. Warhol obviously wasn’t content just soberly replicating the objects and people that represented 50s and 60s America; he also replicated the process by which those objects had come to be. By further removing the presence of the artist from the art, assuming a “businessman and manufacturer as artist” approach, and even incorporating a metaphorical Factory to aid in the production of his work, Warhol himself embodied the ethos that is manifest in his art.

Photo sources:

1) https://artbasel.com/catalog/artwork/19429/Richard-Lindner-Boy-with-Machine

2) https://www.minniemuse.com/articles/musings/the-shoes-of-andy-warhol

3) http://www.moderndesign.org/2009/11/andy-warhol-200-one-dollar-bills.html

4) https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/98.563/

5) https://revolverwarholgallery.com/portfolio/shoes-portfolio/

6) https://magazine.artland.com/stories-of-iconic-artworks-andy-warhols-oxidation-paintings/