November 2018 | Aurora Garrison, Revolver Gallery Curator

Andy Warhol has an intimate relationship with Death. Perhaps so intimate is his relationship with Death, that Warhol’s death has not happened, yet. Each successive artistic generation rediscovers Warhol’s ubiquitous contributions to art, music, film, literature and publishing, and his legacy lives on.

“I don’t believe in death”, Warhol said, “because you’re not around to know that it’s happened. I can’t say anything about it because I’m not prepared for it.”

Somewhere, Warhol must be thinking, “Death where is thy sting?” Because Warhol ain’t feeling his death. Indeed, Warhol’s presence as both an artist and cultural pop icon is as strong today as ever. Warhol’s collectability as the premier artist of the 20th century is undisputed. His artworks are at their highest values.

Exhibit 1: Warhol’s Skull series

By examining the Skull series, created in 1976, we get a better perspective on the indelible Warhol legacy.

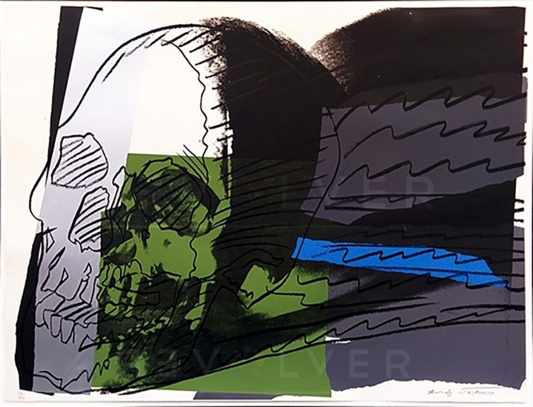

Skull 157 is one of four screen prints we are going to consider here. The work is conceived and created from the original black and white photograph of a human skull resting on a flat surface. The photograph was taken by Warhol’s assistant, Ronnie Cutrone. Reportedly, Warhol purchased the skull at a market in Paris.

Edition: 50, 19 AP – What does this notation mean?

An edition is the controlled number of prints released by a publisher. Between 1976 – 1979, Warhol was his own publisher, under the business name “Andy Warhol Enterprises, Inc., New York”. AP is an abbreviation for “Artist’s Proof”. An artist’s proof is of a quality equal to the edition. This artist’s proof is numbered as AP 19.

Purple, brown and beige are juxtaposed vibrantly with the skull colored in beige and the accent colors of brown and purple underlying the skull, seemingly making the skull move, as if turning, twisting and rotating toward the viewer. Bold wavy black lines run through the colors, with the features of the skull traced with a thinner, more articulate, fine line. Finally, the image is horizontally severed with gray on the bottom and white and black-screened highlights on the top—further popping the skull as if it were a three dimensional image escaping from the work itself.

Based on the photograph taken by Warhol’s assistant, Skull 157 is an example of Warhol’s masterful play with light and shadow, using photography as a way to experiment with light and its relationship to an object. The skull is angled in such a manner to accentuate the forehead and cheekbone. Skull 157 is an example, when compared to the other images in the series, of how brilliantly Warhol animates a static, commonplace object. The individual prints in the entire Skull series vary in the media used (canvas, linen or paper), the color combinations employed by the artist, the sizes of the works in the series and the level of individual vibrancy in each piece.

Warhol’s First Brush With Death in 1968

In 1968 Warhol dies twice on the operating table. After being shot at The Factory, his art studio in New York, by an angry feminist with a revolver, miraculously, Warhol survives. He takes three point-blank shots into his gut, and he lives to talk about the ordeal. But post-shooting Warhol is a changed man. The shooting physically maims him and psychologically scars him, beginning his life-long relationship with death in both his life and art.

“Before I was shot, I always thought that I was more half-there than all-there—I always suspected that I was watching TV instead of living life. Right when I was being shot and ever since, I knew that I was watching television.” Warhol’s Skull series represents an important emotional shift in Warhol’s work, influenced by his 1968 shooting, an event which would profoundly affect his philosophies on both life and art. He attempts to make sense of the shooting, death and his own mortality, by confronting the subject in art.

In 1976, less than 10 years after his brush with death, Warhol painted death in a series of works from the human skull he had picked up while in Europe at a Paris store in 1975. In Warhol’s grappling with death, Death seems to have emerged with the short end of the brush.

Skull 158 is in sharp contrast to the prior rendering of Skull 157. Both reveal Warhol’s indefatigable ability to render and transform an image in a completely different way, with startling and different effects. Here, in Skull 158, the skull has rotated 45 degrees, with the skull’s right side of the face rotated nearest to the viewer. The bold lines in Skull 157 are replaced with fine, artistic lines subtly tracing the outline of the skull and its features of teeth and eye sockets. Wherein Skull 157’s gaze averts the viewer, Skull 158’s face and vacuous eye sockets are staring, confronting the viewer with both its gaze and shocks of mustard, blue, green and rose bursting in a kaleidoscope of color and vibrancy. A menacing shadow runs from the left of the portrait to the right accompanied by a line sketch that abstractly suggests a train track, again giving movement and a dynamic tension to the image.

With both his prized human skull and his near-death experiences in hand, Warhol resurrects the skull image to reinterpret the classical vanitas or vainites genre with a modern day Pop Art twist. Warhol’s hand-held inspirational Skull looks like it is straight out of the Hollywood prop department, invoking Hamlet’s soliloquy on Hamlet’s friend Yorick’s death in the infamous grave yard scene in Act 5: “Alas, poor Yorick, I knew him, Horatio.” But only Warhol can make Art out of a prop, or out of a soup can, for that matter.

Historically, in art, the human skull represented the theme “vanitas”, known as mortality or the shortness of life. Here, the the skull is simply a motif; a part of Warhol’s desire to evoke the human condition.

The third in this four-part series, Skull 159, is a shock. Again, the indefatigable artist Warhol and his human skull have found yet another resting place and positioning of the skull’s face within the context of the 30” x 40” rectangular format. This image is dead center. The skull’s visage is perfectly aligned to the viewers in a full, frontal confrontation by and between the viewer and the skull. Yet, there is a third, invisible face the viewer immediately recognizes though he is not in the frame, he is behind it. Like no other artist in his time, to view a Warhol is to also see the icon behind the work of art itself.

It’s been quipped that the greatest work of art by Warhol is the icon of Warhol.

We all see him—the shock of white hair, the thin pale face, the glasses and the look, the Mona Lisa smile of Warhol that intimates that he knows something we don’t, and that Warhol sees something we can’t. This is the mystery of Warhol, the artist as enigma.

And in Skull 159, the icon behind the canvas is all too visible. Here, Warhol rotates the mask of Death itself and asks us—as he did himself after his shooting in 1968—to confront our own mortality and our deaths. In vanitas, rebooted in 1976, Warhol is asking us to confront the violence of executions in the electric chair, violent airplane and car crashes and the ephemera of life itself. In Skull 159, the full oeuvre of Warhol’s art and our culture of violence and death are staring at us; it’s like looking down the long end of a gun’s barrel. Warhol confronts and shocks with the full face of death and colors of violence spanning from stabs of yellow, and pink-red hues to blood red in the foreground, with ominous blue-grey mountains of death and the afterlife in the background, but also in our not too distant futures.

Warhol taunts us in Skull 159, as if saying, “I confronted and stared down Death. What’s your reaction?” As he writes in his book, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, “Sometimes people let the same problem make them miserable for years when they could just say, “So what.” “My mother didn’t love me.” So what. “My husband won’t ball me.” So what. “I’m a success but I’m still alone.” So what. I don’t know how I made it through all the years before I learned how to do that trick. It took a long time for me to learn it, but once you do, you never forget.”

The Introduction of the Culture of Death in America

Warhol in 1976 is foreshadowing America’s first foray into the American obsession now cryptically referred to as our “culture of death” through his Skull series. Paul McCartney famously wrote “Let It be” as a response to times of trouble and fear of death. “Let It Be” was written in the year Warhol was shot and first performed the following year.

Warhol, predictably adopts, “So what”, as his personal mantra for dealing with trouble, death and life’s fleeting nature. Paintings created in the vanitas style confront us with the transience of life, the futility of pleasure, and the inevitability of death. Warhol resurrects the centuries-old motif in his Skull series with a decidedly Pop Art twist on the old tradition.

The old masters needed a table and a whole box of stuff in their still life paintings to force their contemporaries to contemplate their lives and perhaps make a mid-life course correction by understanding life’s fleetingness. Warhol uses one skull and removes the table, saying, “I never understood why when you died, you didn’t just vanish, everything should just keep going on the way it was only you just wouldn’t be there.” Or, in other words, his final analysis with death is, “So what?”

So Warhol, in his ironic way, confronts Death through his art, and beats Death in his Warhol way by achieving an immortality of sorts in his life after death through his art. We think Warhol would smirk at the idea that his Skull series somehow cheats Death.

Skulls 160 completes the four-part series in a remarkable fashion. But you as viewer should confront this last Warhol visage of death, and draw your own conclusions what the artist behind the work was thinking, and most importantly, what does Skull 160 make you think and feel?

Warhol, in the end, challenges us, “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings . . . and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.” The choice is ours. Do we believe Warhol at his word?

A Warholian Experiment with 11 Warhol Paintings in Chicago

Recently, I conducted an artistic and social experiment. I went to a highly esteemed museum with 10 Warhols in one large room and a single Marilyn hanging in the entry for an exhibition of the works of 20th century artists. And I sat there for a few hours, counting the viewers for each of the 10 works, counting the photographs taken of each of the 10 works of art, and finally, how many selfies were taken standing next to which famous Warhol. Like a naturalist working in the field, I put a hash mark for every time one of the 10 paintings was viewed, photographed and captured in a selfie.

I would say that Warhol is wrong when he says, “There’s nothing behind” his art. Quite the opposite. Thirty years after his death in 1987, Warhol has never been more popular, more loved or more enjoyed. Unlike any other artist in the gallery that day, the Warhol pieces were interactive with the viewers engaging with each painting. And the world is still trying to catch up with the nuances and depth that Warhol has offered the world through his art, his icon and his legacy.

Warhol cryptically has the last word—and last laugh—on his cheating Death both in 1968, 1987 and now, “I always thought I’d like my own tombstone to be blank. No epitaph, and no name. Well, actually, I’d like it to say ‘figment’.”

You can view Andy Warhol’s grave 24/7 on the live video cam of his grave site at: https://www.earthcam.com/usa/pennsylvania/pittsburgh/warhol/ to see if “figment” is carved on his stone.

Perhaps Warhol has cheated Death by outliving and surpassing his own 15 minutes of fame through his art, his iconic fame and his legacy. What would Andy think? Probably, he would deadpan, “So what?”