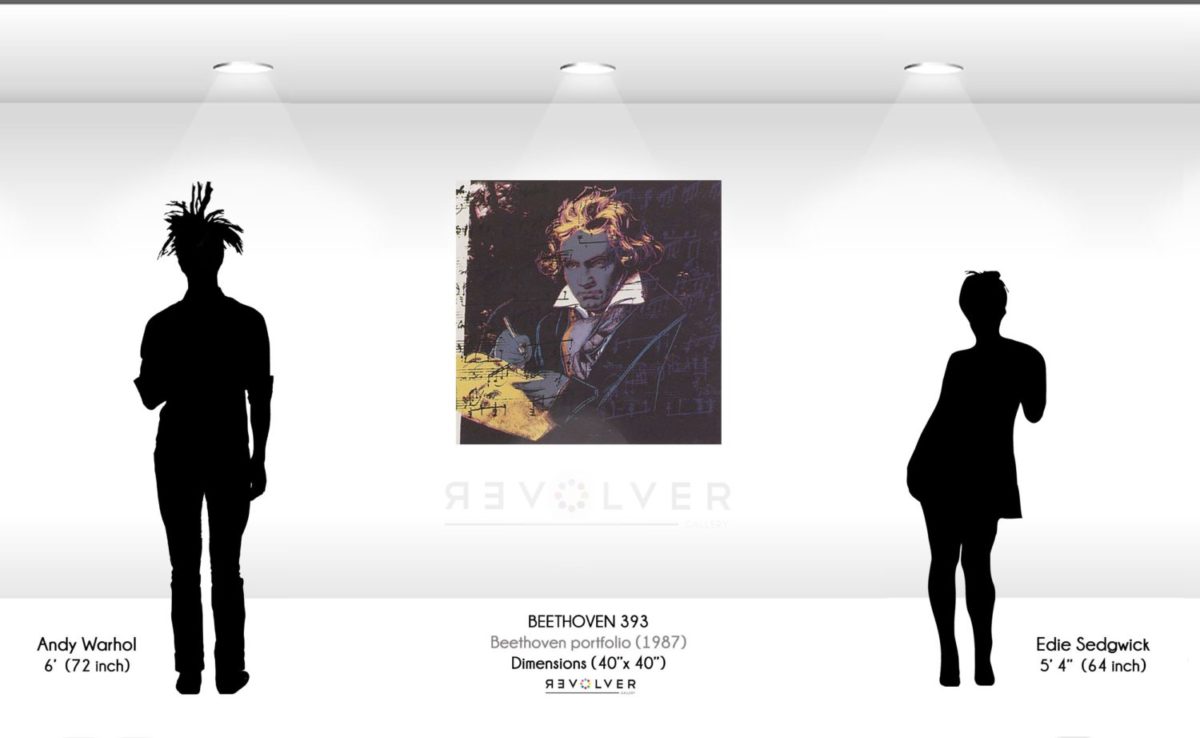

Beethoven 393 by Andy Warhol is one of four screen prints from the 1987 Beethoven series. Whereas much of Warhol’s earlier portraits focused on prominent celebrities, the Beethoven series represents a new direction; although the connection with his earlier works is still clear. During the 1980s, Warhol commented on the similarity between the commodification of historical and political figures and that of celebrities. This commentary extends to other series Warhol published during this time, such as his work on prominent cold war political figures like Mao Zedong and Lenin.

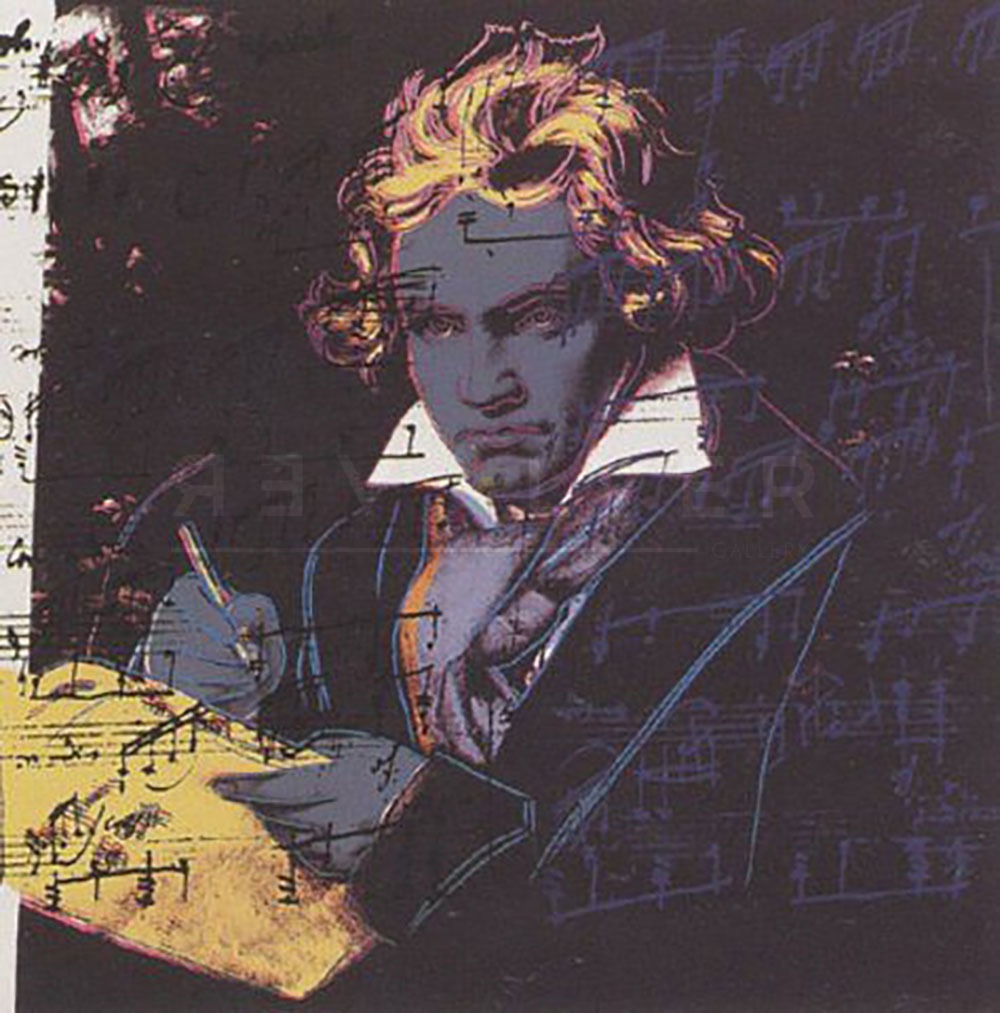

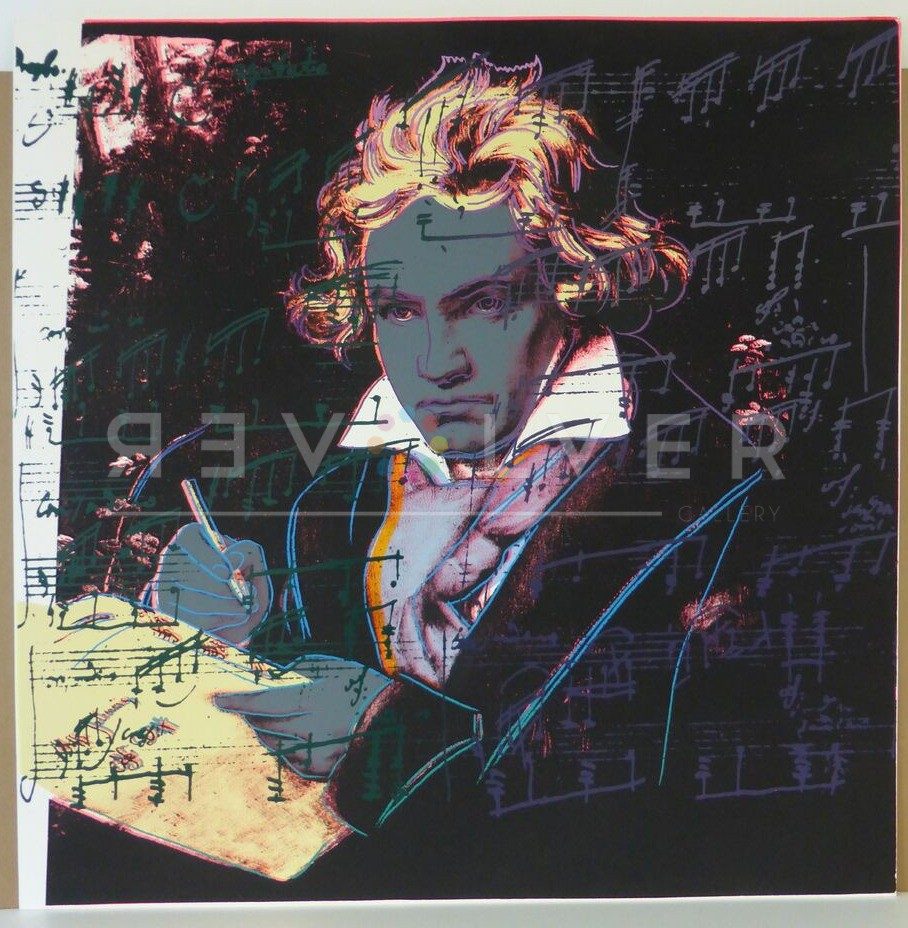

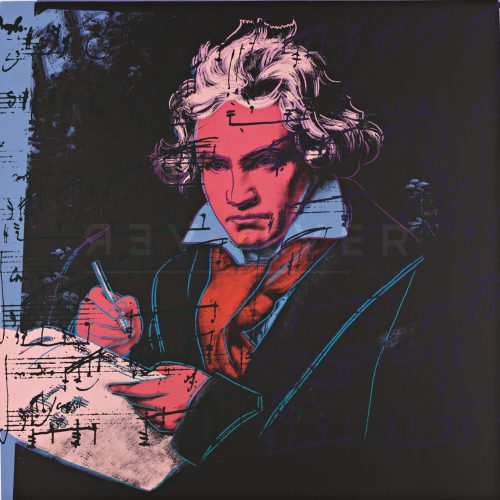

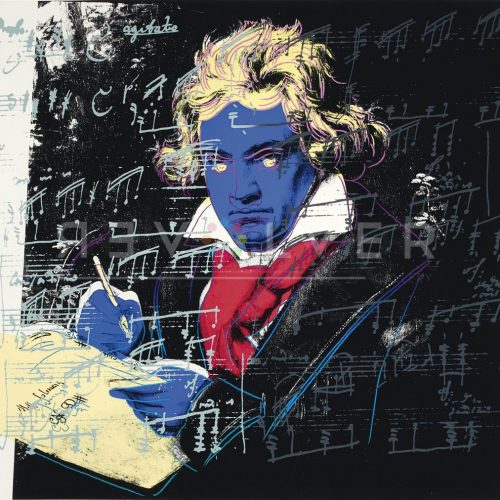

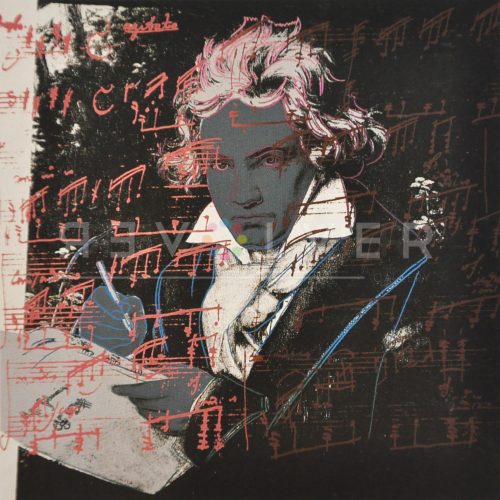

Beethoven 393 is based upon a portrait by neoclassical painter Karl Stieler. While the original painting seemed to suggest an intensity and power reflective of the cultural optimism in Germany at the time, Warhol is more interested in exploring the introspective side of Beethoven. Additionally, he explores how we think of him as an icon of classical music. The musical score and the coloration of Beethoven’s face shift between complimentary and opposing color configurations throughout the series. (See Beethoven 390 and 391). Beethoven 393 in particular suggests a more sickly hue in the mixed greenish grey of Beethoven’s face and hands, lending the series a more ominous tone.

Warhol contextualizes Beethoven’s stare amongst the musical notation of his “Sonata No.14,” one of his most famous works. In Beethoven 393, Beethoven’s face seems to be staring out into the musical notation that will come to define his celebrity status. Is the man disappearing behind the work? Or, is this new context putting the music and the process of musical writing into question, causing us to think twice about the experience of the composition process the next time we listen to a Beethoven work?

The Beethoven series comes at a critical point in Warhol’s career, and thus presents us with an interesting meditation on common ideas about fame and artistic genius for several reasons. Ludwig van Beethoven is undoubtedly one of the most influential composers of all time. Goethe—another artistic giant from 18th century Germany—said of Beethoven that “his talent amazed me; unfortunately he is an utterly untamed personality, who is not altogether wrong in holding the world to be detestable, but surely does not make it any more enjoyable…by his attitude.” (Warhol painted Goethe, as well).

Perhaps Warhol empathized with Beethoven’s cynical worldview as well as his tragic battle with deafness later in life. The fact that Warhol completed Beethoven 393 in the last year of his life while struggling with serious health issues suggests a self-identification with the composer that is particularly poignant. Regardless, there is certainly something defiant in the way Warhol places the musical notation on top of the artist’s portrait.

Beethoven 393 is also highly characteristic of Warhol’s obsession over his own appearance. He brightly illuminates the parchment and Beethoven’s hair, but mutes the skin and the notes, separating them from the rest of the painting. In Warhol’s book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again), Warhol claims that “If someone asked me, ‘What’s your problem?’ I’d have to say, ‘Skin.’” In Beethoven 393, Warhol displays a creative conflict between the creativity of the artist and the packaging of famous figures. This results in a portrait of sensory experience that challenges the monotony of artistic conventions—an achievement that both artists were well known for.

Photo credit: Portrait of Beethoven with the manuscript of the Missa solemnis by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1820.