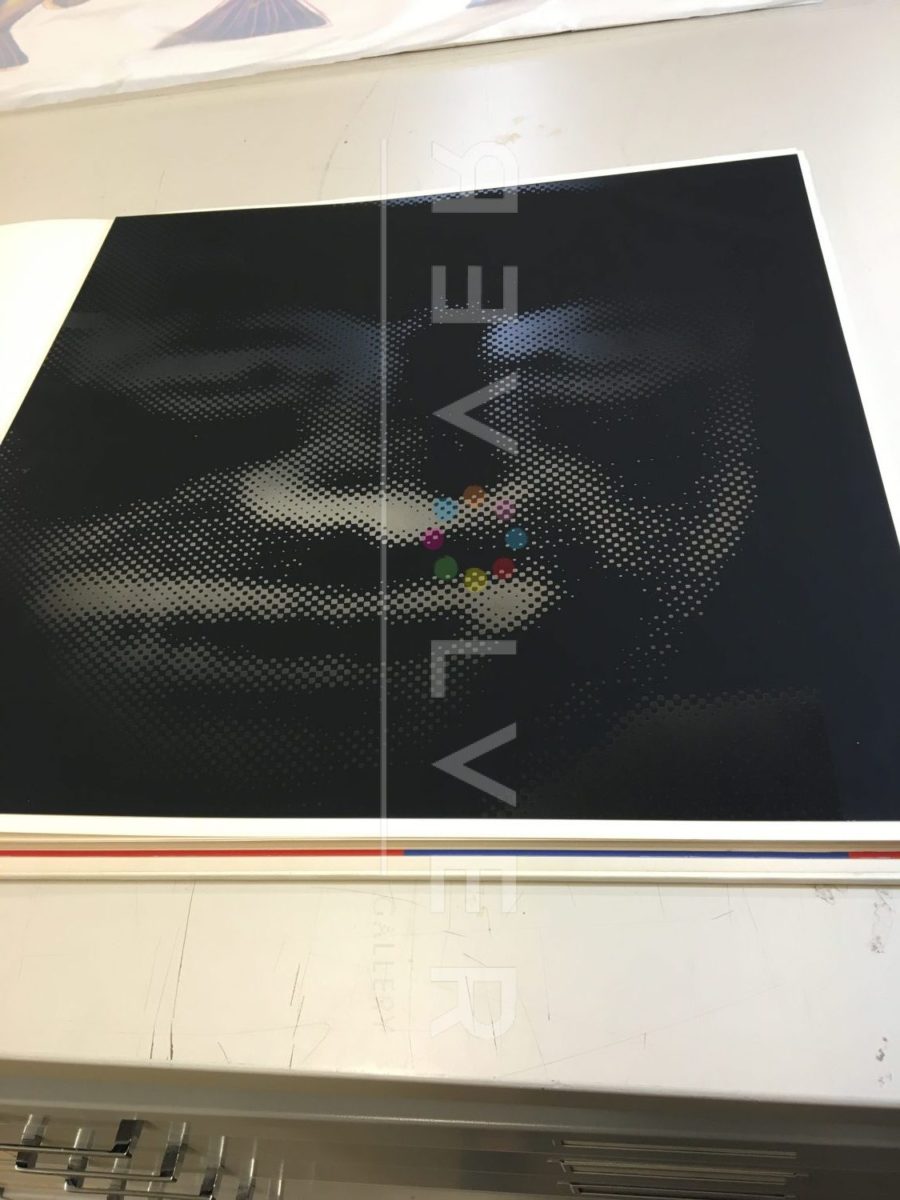

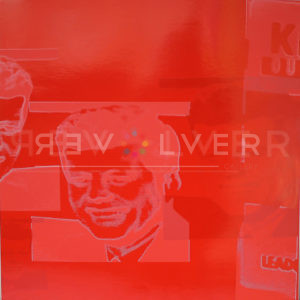

Flash 32 is a screenprint by Andy Warhol from his 1968 portfolio titled Flash – November 22nd, 1963. The controversial project contained 11 screenprints of different mass media images related to the assassination of John F. Kennedy. The prints are distinct from Warhol’s other ventures due to their faded imagery, conservative color schemes, and foreboding tone. These deviations from Warhol’s typical style capture trauma with a remarkable sobriety. With Flash 32, which depicts the late president’s famously charismatic smile, Warhol memorializes the moment by juxtaposing JFK’s liveliness with the series’ grim awareness of the inevitable.

Among many (more positive) aspects of life, the complex relationship between society and tragedy fascinated Warhol. It is likely that he noticed the simultaneous yet opposing feelings of fear and attraction our society has with violence. This is a theme he previously explored with the Death and Disaster, as well as later works like the Skull screenprints. Flash, however, is unique in its depiction of a nationally recognized moment, a distinction which garnered the series much controversy. After all, Warhol released Flash 32 less than five years after the JFK assassination.

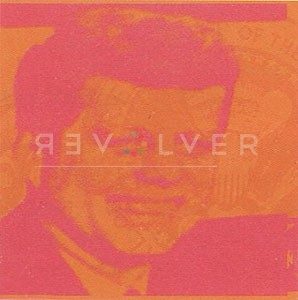

Though Flash 32 is unique in many ways among Warhol’s oeuvre, the base image is not unlike the images Warhol would select for his colorful depictions of celebrities. Warhol’s obsession with fame gave him a unique eye for the recognizable characteristics of a celebrity’s image. The photo he selects for John F. Kennedy is no exception; his boyish good looks and charisma made him a perfect muse for Warhol’s representation of public image. In Flash 32, Kennedy sports his famous charming smile, putting the viewer under his spell. The image captures the iconic “Kennedy Effect” by which the young politician rode into the White House. Additionally, the handsome closeup paired with the knowledge of the president’s impending demise infuses the print with a whole montage of emotions.

If the image Warhol selected perfectly encapsulates JFK’s living persona, then the presentation of Flash 32 is a shocking and profound depiction of the tragedy of his death. Black and gray hues drown out the image, making Kennedy’s face almost unrecognizable against the bleak background. The sharp contrasts that characterize Warhol’s other portraits are absent; Kennedy’s face hangs in the ether, vanishing when the viewer squints at the print. The effect is an intense sense of foreboding–Kennedy’s shining grin shows no understanding of the fate that awaits him. It’s also a decidedly mature meditation on the trauma of the moment; a gray sheet cloaks the once-lively image of Kennedy, demonstrating the brooding mortality that swallowed the entire scene.

Flash 32 is this an undeniably provocative image. By subverting the expectations of his own work, Warhol is able to turn his celebrity-focused style into a commentary on the way society views tragedy and violence. Does this image of Kennedy—widely syndicated and showing him in his last moments—suggest that gravity weighs equally on both tragedy and fame? Or do the subdued hues and faded imagery that separate Flash 32 from so much of Warhol’s work suggest the inevitability of a mortality that renders everything else superficial? Warhol leaves the viewers with no easy answers. Flash 32 stands out as one of the most thought-provoking pieces in his 1960s body of work.

Photo credit: Undated headshot of John F. Kennedy, 35th President of the United States. Washington, DC, USA. Photo by White House via CNP.