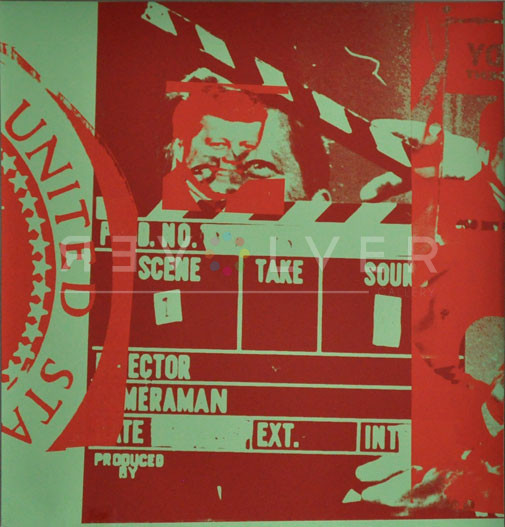

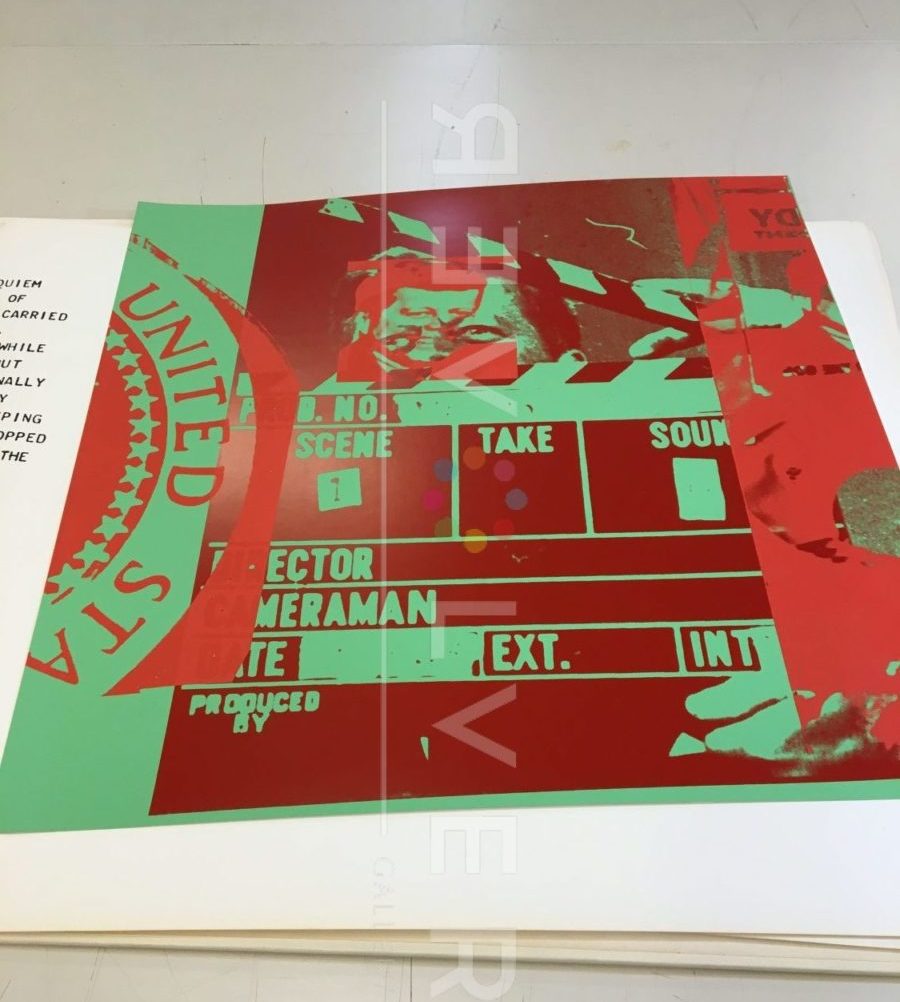

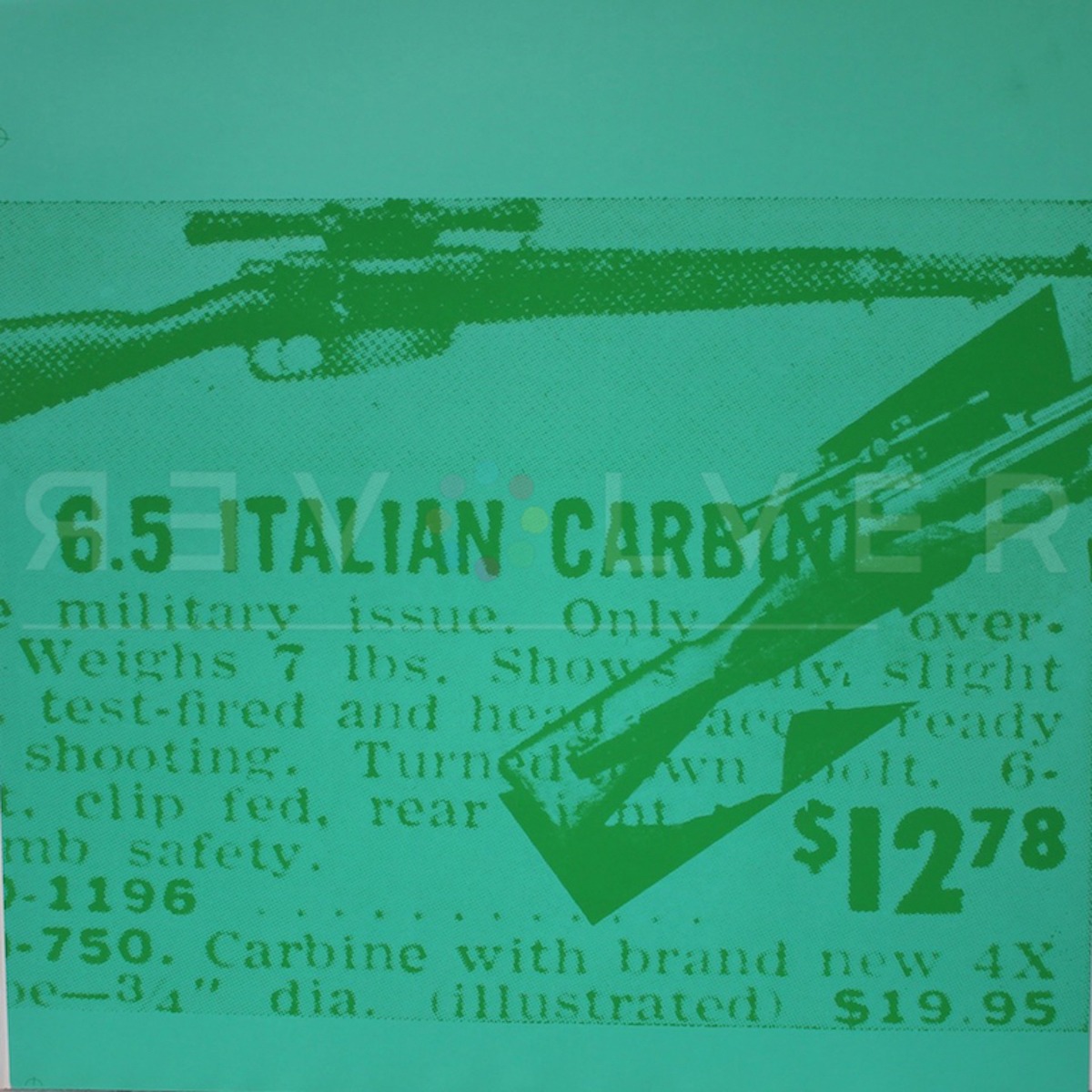

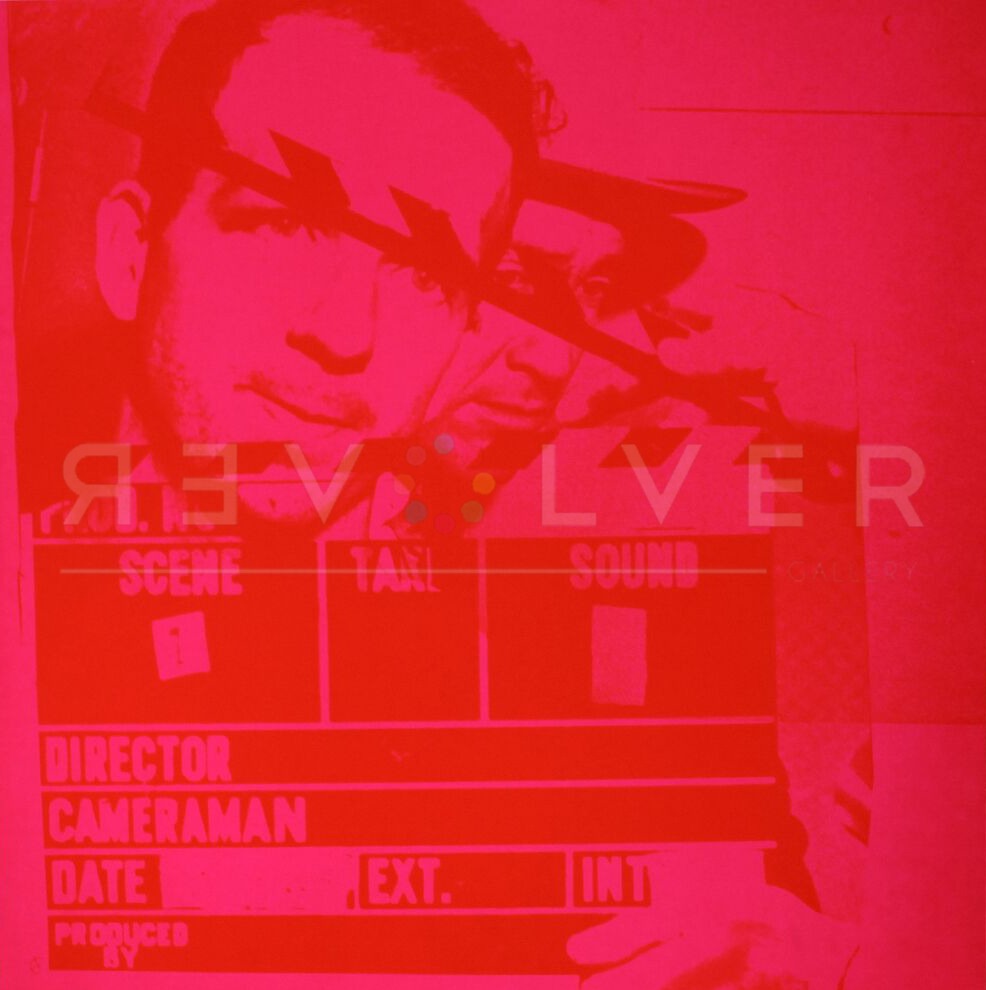

Flash 40 is a screenprint by Andy Warhol included in the artist’s Flash series from 1968. By using imagery from the barrage of media coverage that followed John F. Kennedy’s assassination on November 22nd, 1963, Flash 40 serves to re-contextualize the murder of the President. The print is one of eleven in the series, which Warhol originally presented alongside newswire teletype dramatizing the national tragedy. The series uses various material from newspaper articles, campaign ads, and other mass-media outlets. The use of foreboding imagery in Warhol’s repertoire is frequent. The exploration of tragedy and how the media crafts it is a common theme in Warhol’s canon. For example, the same foreboding aura from the Flash series is present in the Death and Disaster collection, and in individual series such as Electric Chair.

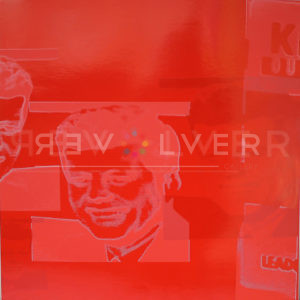

Warhol already maintained an interest in the high-profile Kennedy presidency–particularly relating to Jacqueline Kennedy. In 1966, Warhol produced three different works titled Jacqueline Kennedy (Jackie) ( I, II, & III). They served to bring attention to the first lady and the mythos she developed around the tragedy. The series doesn’t intend to reflect the blitz of headline articles that sensationalized her grief. Instead, Warhol found her defiance to the media’s onslaught impressive. The Flash series then casts our attention to the media’s craftsmanship in regards to how we remember the Kennedy assassination.

According to Warhol, JFK’s death did not initially stir his emotions the same way it did for most Americans. In order to soak up as much viewership as they could, the media emotionally amplified the event. This bothered Warhol, and prompted his muted reaction. “I’d been thrilled having Kennedy as president; he was handsome, young, smart—but it didn’t bother me that much that he was dead” Warhol admits. “What bothered me was the way the television and radio were programming everybody to feel so sad. It seemed like no matter how hard you tried, you couldn’t get away from the thing” (POPism, The Warhol Sixties, 1980). Warhol did not ponder the idea of his own death. Rather, he viewed one’s death as unimaginable, because we are not around to know that it has happened.

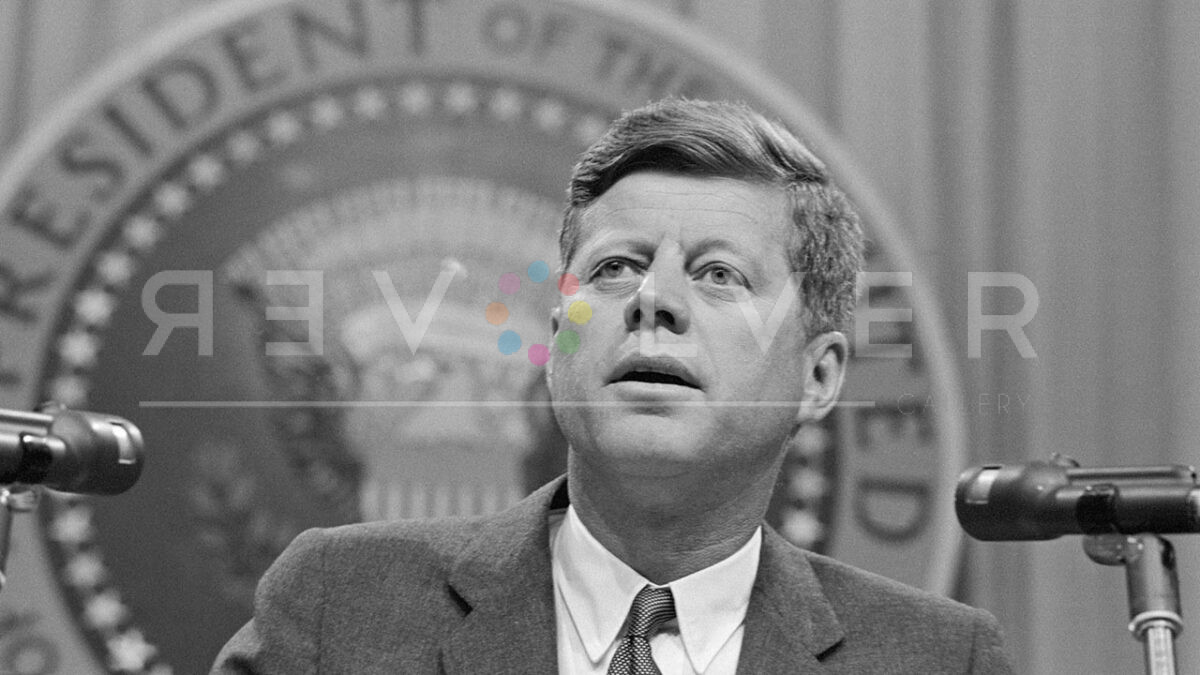

Flash 40 employs the aesthetics of media production by featuring a clapperboard over the face of JFK, whose image was heightened to that of a movie star by the press. Thus, the clapperboard blurs the line between the reality of his death and the media spectacle that became of it. It is no wonder why Warhol chose to depict the Kennedy’s—their charm was akin to that of Mick Jagger or Marilyn Monroe. The Flash series acts like a foreboding warning to the construction of an icon. It explores how the media presents tragedy to the public, as well as our memory of such events. Ultimately, Flash 40 is one of Warhol’s most thought-provoking images, from the more macabre region of the artist’s work.

Photo credit: President John F. Kennedy speaking at a conference on March 29, 1962. (© Bettmann via Getty Images)