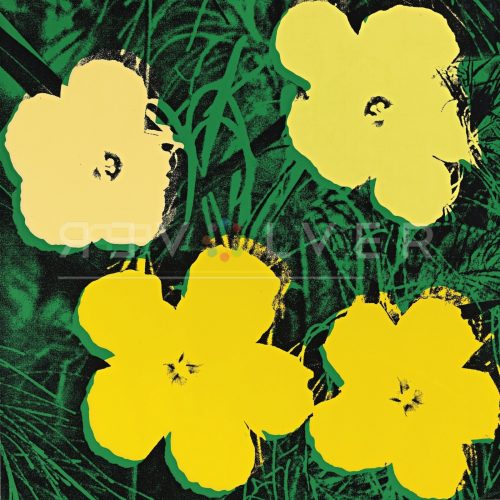

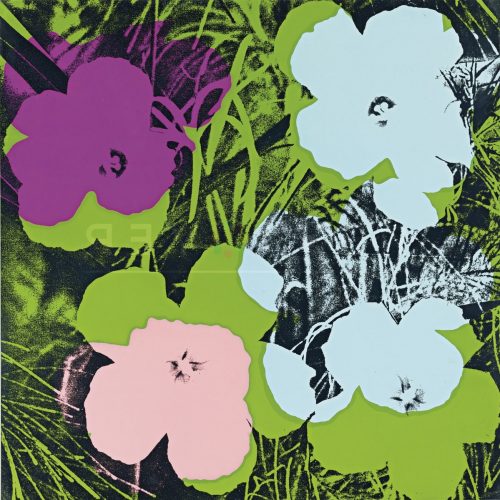

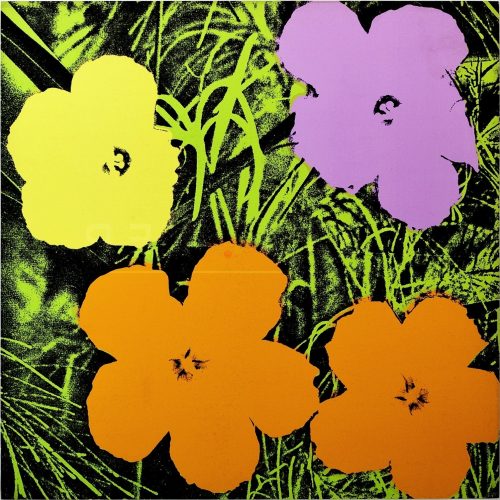

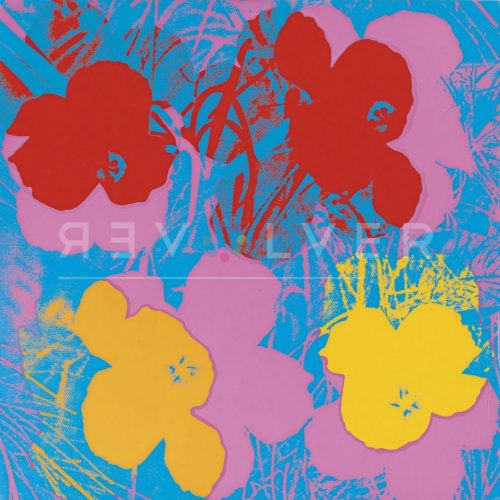

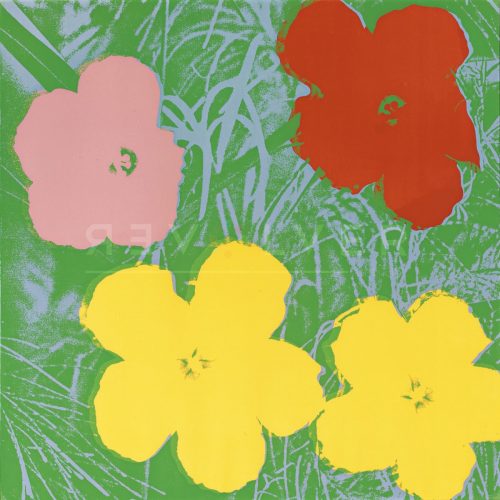

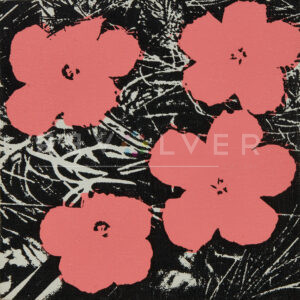

The Flowers complete portfolio by Andy Warhol contains ten psychedelic screenprints of flowers, printed in 1970 by Aetna Silkscreen Products, Inc. The images in the portfolio are based on a photograph by nature photographer Patricia Caulfield. The subject is the Mandrinette flower, which is known for its vibrant pink color and ethereal silhouette.

In the summer of 1964, Warhol was busy deciding what to paint for his first opening at the Leo Castelli Gallery. The move from Stable Gallery to Castelli indicated a pivotal moment in Warhol’s career, not to mention the rise of Pop itself. The gallery owner (once described as “the acknowledged dean of contemporary art dealers”) moved beyond Abstract Expressionism, featuring artists like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg as early as the mid-1950’s. It was time for a new wave, and Pop—with its unapologetic consumerism and mass appeal—wholly represented the current moment.

Directly before Flowers, Warhol chose to feature macabre subjects in a body of work called Death and Disaster. Henry Geldzahler, art curator and close acquaintance of Warhol, influenced this period. One afternoon while the two ate lunch at Serendipity, he showed Warhol a newspaper headline titled “129 Die in Jet.” Death and violence fascinated Warhol, especially the constant rate at which they were doled out in the media. When Geldzahler stopped by the Factory in 1964, he made another fateful suggestion that steered Warhol in a new direction.

“…I looked around the studio and it was all Marilyn and disasters and death,” Geldzahler recalled. “Andy, maybe it’s enough death now.’ He said, ‘What do you mean?’ I said, ‘Well, how about this?’ I opened a magazine to four flowers.” The publication, titled Modern Photography, displayed a photograph of hibiscus flowers taken by Patricia Caulfield.

Warhol took his trusted friend’s advice. Before creating the full portfolio in 1970, Warhol composed a set of large-scale Flowers paintings. At their first showing at the Castelli Gallery in 1964, the entire exhibition sold out. The works went on to become Pop masterpieces and some of Warhol’s most successful and recognizable compositions. Warhol’s Flowers openly ridicules the seriousness of Abstract Expressionism, flattening out details to depict nature itself as mechanical and commoditized rather than romantic. At the same time, his use of contrast and brilliant Day-Glo hues gives the flowers a striking effect and the prints remain easily marketable due to their classic subject matter.

Though the flowers appears bright and jocund, they are not without their shadows. By 1963—one year prior to their debut—Marilyn Monroe had committed suicide, President Kennedy had been assassinated, and police were clashing with Civil Rights protestors across the nation. As these violent events unfolded, Warhol worked on pieces like Electric Chair, Race Riot, and Ambulance Disaster. While Geldzahler succeeded in persuading Warhol to shift subjects, echoes of darker realities still exist in the Flowers.

“Lou Reed, Silver George Milloway, Ondine, and me – we all knew the dark side of those Flowers,” recalled Warhol’s assistant, Ronnie Cutrone. “Don’t forget, at that time, there was flower power and flower children. We were the roots, the dark roots of that whole movement. None of us were hippies or flower children. Instead, we used to goof on it. We were into black leather and vinyl and whips and S&M and shooting up and speed. There was nothing flower power about that. So when Warhol and that whole scene made Flowers, it reflected the urban, dark, death side of that whole movement.”

In 1966, Patricia Caulfield sued Warhol for appropriating her original photograph and won her case. Though the trial upset Warhol, it also drove him to start experimenting with a new medium. “He opted to start taking his own photographs,” Gerard Malanga explained. “His entry into photography vis-á-vis his creation of silkscreen paintings was done out of necessity.”

The Flowers series marks a transformational time in Warhol’s career as well as art itself. It also displays Warhol at his best, accentuating his uncanny ability to bring hidden cultural intersections to the foreground. In the Flowers complete portfolio, there is nature versus industry, tradition versus modernity, light versus dark, death versus life. Through the juxtaposition present in his artwork, Warhol shows us where these opposing forces connect, thus piecing together a greater whole.

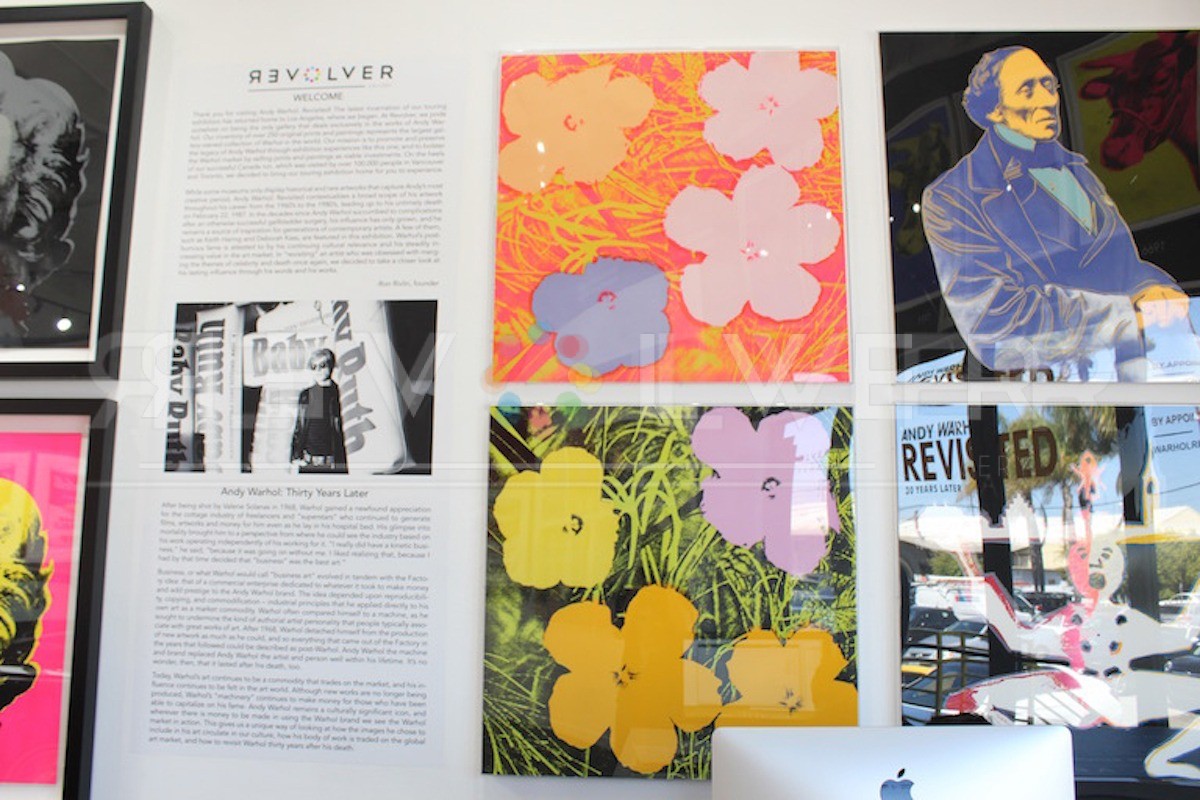

Flowers Portfolio as Part of Andy Warhol’s Larger Body of Work

Among Warhol’s work, the Flowers prints are notable for their delicacy. Borrowing from magazines and a wallpaper catalogue, Andy Warhol first cropped and abstracted the images. Then, with characteristic inversion, he personalizes the flower prints, adding by hand delicate washes of Dr. Martin’s aniline watercolor dyes.

Warhol published these works in 1970, years after he originally conceived his Flowers concept. He first created seven monumental-scale paintings from the famous Flowers series, which the artist showed at a sell-out exhibition at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York in 1964 and with Galerie Sonnabend in Paris in May 1965. The two shows included densely hung canvases of flowers in various sizes and brilliant Day-Glow hues.

Photo credits:

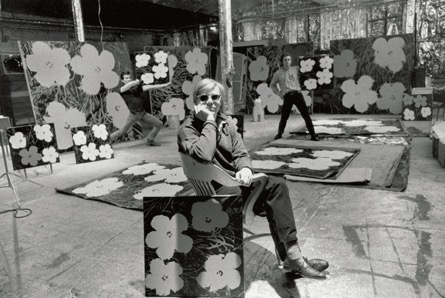

1- Andy Warhol with ‘Flowers’ at The Factory, 1964. Photo by Ugo Mulas.

2- Andy Warhol silk-screening Flowers, 1965-7. Photo by © Stephen Shore.