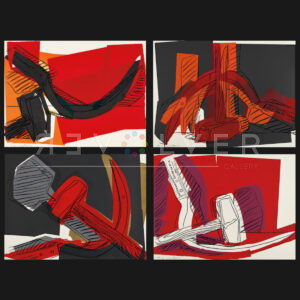

Andy Warhol’s Hammer and Sickle 162 is one of four screenprints from his 1977 Hammer and Sickle portfolio. Warhol became inspired to create Hammer and Sickle upon observing popular communist graffiti during a trip to Italy the year prior. Though these symbols are almost inextricable from the communist ideology, Warhol was fascinated by the sensationalism of the symbol during the heightened cold war tensions of the time. Originally, the hammer and sickle symbolized the proletariat union of industrial workers and farmers. Warhol saw the symbol for its unique cultural position, as well as its importance as a symbolic reflection of the current political climate. He also found inspiration in its repeated use, and the way its meaning shifted over time across its various iterations.

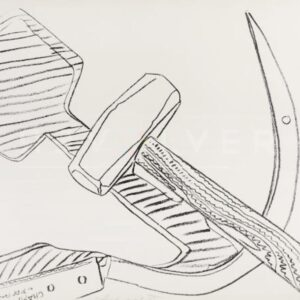

Hammer and Sickle 162 restructures the communist iconography while maintaining its key elements. Upon returning from his trip, Warhol asked his assistant Ronnie Cutrone to create source images for the prints. Cutrone scoured communist bookstores in New York for images of the hammer and sickle, but Warhol rejected them all; he saw the images Cutrone found on flags and in books as flat and lifeless. In the end, Cutrone purchased a hammer and sickle from a hardware store and photographed the tools in a variety of positions. Warhol selected a handful of Cutrone’s photos to sketch, which formed the basis of the Hammer and Sickle prints.

In 1977, Warhol exhibited his Hammer and Sickle portfolio under the title Still Lifes at the Castelli Gallery in New York City. Though this portfolio was laden with meaning, Warhol was determined to use it as an opportunity to deconstruct the symbol that had become inextricably tied to communism. By calling the exhibit Still Lifes, he encouraged his audience to try to divorce the objects from the ideology while simultaneously playing on public perceptions of communism.

In Hammer and Sickle 162, Warhol depicts the tools in white with details sketched in black. The shadows of the hammer and sickle are blocked out in a deep reddish purple with rough black lines for shading. The entire piece appears against a background with inexact blocks of bright red. The brightest print in the series, Hammer and Sickle 162 is the only print in this portfolio to depict the hammer and sickle in white. It is also the only print that does not utilize large swaths of black.

Where Hammer and Sickle 161, 163, and 164, recall violence and bloodshed, 162 takes a different approach. By depicting the hammer and sickle in such a light color palette Warhol illustrates the idealism inherent to communism. The juxtaposition between the bright white symbols and ominously dark shadows may represent the disparities that arose between communist ideals and realities.

Ultimately, in Hammer and Sickle 162, Warhol invites his audience to examine the relationships between art and propaganda. The series exhibits Warhol’s powerful ability to appropriate imagery, re-introduce it within an aesthetic context, and welcome an appreciation for the symbol from the standpoint of its social meaning. This firm grasp on the conceptual utility of Pop Art is one of the reasons Warhol’s art remains so relevant and powerful years later.

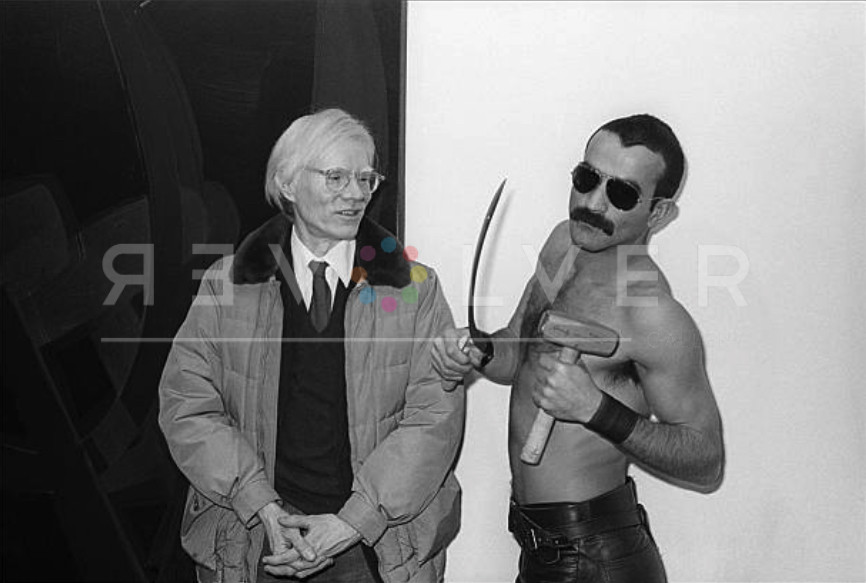

Photo credit: Andy Warhol poses with Victor Hugo, who holds the original hammer and sickle artist used in the works, at the opening of his “Hammer & Sickle” show at the Castelli Gallery, New York, New York, January 11, 1977. Photo by Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images.