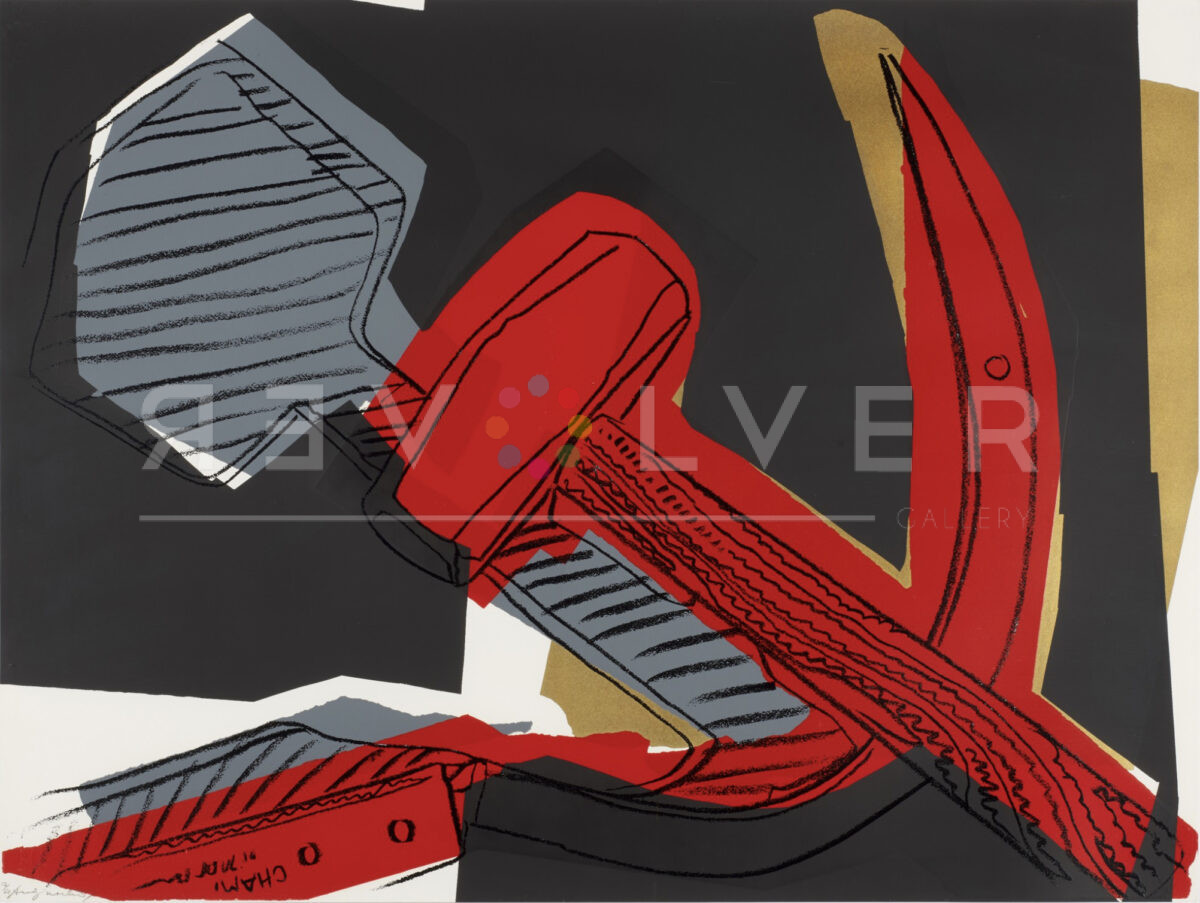

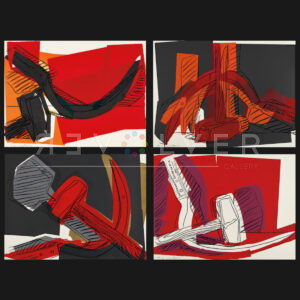

Hammer and Sickle 164 by Andy Warhol is one of four screenprints from the 1977 Hammer and Sickle portfolio. Warhol became inspired to create the series after a trip to Italy the year prior. While in Italy, Warhol took note of common graffiti depicting the hammer and sickle, originally symbolizing the union of industrial workers and farmers during the Russian Revolution. Fascinated by the repetition of the image, and its political significance during heightened cold war tensions, Warhol returned to New York to recreate the communist iconography.

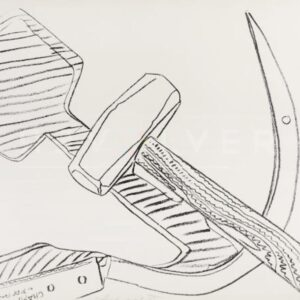

Hammer and Sickle 164 restructures the universally-recognized symbol while maintaining its key elements and symbolic value. Under Warhol’s instruction, Ronnie Cutrone scoured communist bookstores of New York city searching for an appropriate source image for the prints. Warhol found all of the traditional images to be too flat, so Cutrone ended up purchasing a hammer and sickle from a hardware store. “The answer was to go down to Canal Street, into a hardware store, and buy a real hammer and a real sickle. Then I could shoot them, lit with long menacing shadows. And add the drama that was missing from the flat-stenciled book versions” (Ronnie Cutrone, Hammer and Sickle, 2002).

Warhol generates new perspectives of the symbol by depicting the tools in various positions throughout the full series. Hammer and Sickle 164 resembles the original iconography most closely, due to the diagonal positioning and the crossing over of the tools. Warhol maintains his notable style with blocked color swatches and linework shading, while harnessing the infamous red color of the communist flag.

For obvious reasons, Hammer and sickle 164 and its counterparts garnered controversy. When asked about the subject matter and desire to create such a portfolio, Warhol simply responded, “we went off to the store and bought a hammer and sickle. Bob (editor of Interview Magazine) has a lawn to cut.” Though Warhol also created works depicting communist figures Mao Zedong and Lenin, the Hammer and Sickle portfolio doesn’t function as an affirmation of the symbol’s acquired meaning. The portfolio detaches the symbol from its use as a political statement, instead reflecting the sensationalism of the image and its overall potency as a political icon.

Warhol’s bold approach to addressing the political issues of the time showed that he was cognizant of political unrest and the importance of creating a statement through art. He chose the feared symbol of communism and contrasted it with the lighthearted nature of the Pop Art feel, in order to evoke satire as a personal commentary on the Cold War. Warhol’s awareness of the ties and connotations that are attached to the imagery of the hammer and sickle are very much present.

Ultimately, Hammer and Sickle 164 exhibits Warhol’s powerful ability to appropriate popular symbols and invite his audience to view them within an aesthetic framework, where the usual function of the symbol may fall away. At the same time, the bare meaning of the imagery remains, and allows viewers to appreciate the cultural power of the symbol without necessarily affirming its use in reality. With Hammer and Sickle, Warhol reveals the blurred line we often find between propaganda and art.

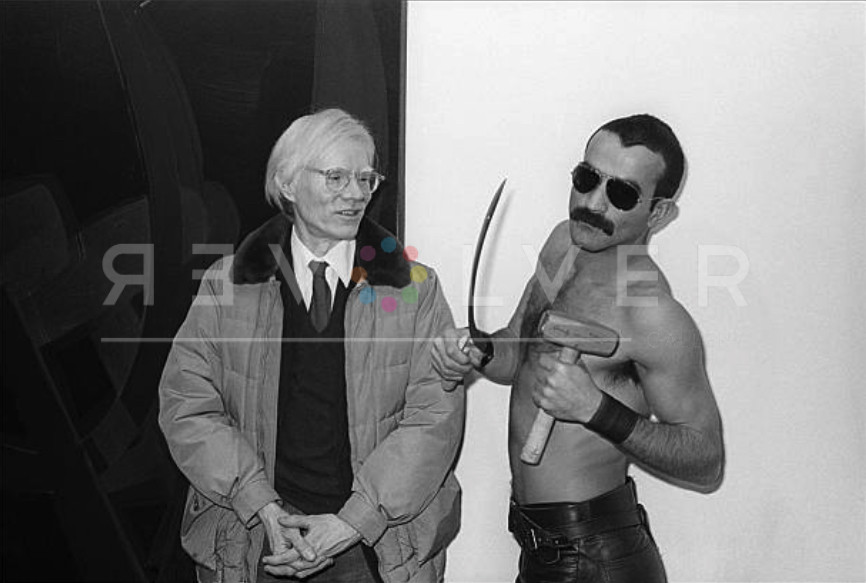

Photo credit: Andy Warhol poses with Victor Hugo, who holds the original hammer and sickle artist used in the works, at the opening of his “Hammer & Sickle” show at the Castelli Gallery, New York, New York, January 11, 1977. Photo by Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images.