Hammer and Sickle (Special Edition) 170 is one of seven prints in Andy Warhol’s 1977 Hammer and Sickle (Special Edition) portfolio. This series illustrates the printing progression of Warhol’s 1977 Hammer and Sickle four-print portfolio. Warhol was inspired to create the original Hammer and Sickle portfolio upon noticing communist graffiti on a trip to Italy. Under communist control, the hammer and sickle represented the union of industrial and agricultural workers, but to Warhol the symbol was apolitical.

In an interview shortly before he completed the original Hammer and Sickle series, Warhol was asked if he was a communist. Though he answered in the negative, later, pondering the question with Bob Colacello, Warhol famously said, “Maybe I should do real Communist paintings next. They would sell a lot in Italy.” In saying this, he demonstrates the separation between imagery and meaning that he aimed for with the series. When Warhol observed the graffiti featuring this symbol in the 70s, he perceived the hammer and sickle as a repeated image of pop culture; a commodified symbol, not a political statement.

For the original series, Warhol instructed his assistant, Ronnie Cutrone, to find appropriate source images to create the pieces. However, Warhol was dissatisfied by the flatness of the reproductions Cutrone found for him in Soviet history books and on flags. Warhol instead had Cutrone purchase a hammer and sickle and photograph them in different positions. From these photographs, Warhol sketched his own reproduction of the hammer and sickle for the Hammer and Sickle portfolio. Intent on de-contextualizing the symbol, Warhol exhibited the portfolio in 1977 under the title Still Lifes at the Castelli Gallery in New York City, purposefully omitting any reference whatsoever to communism or the hammer and sickle.

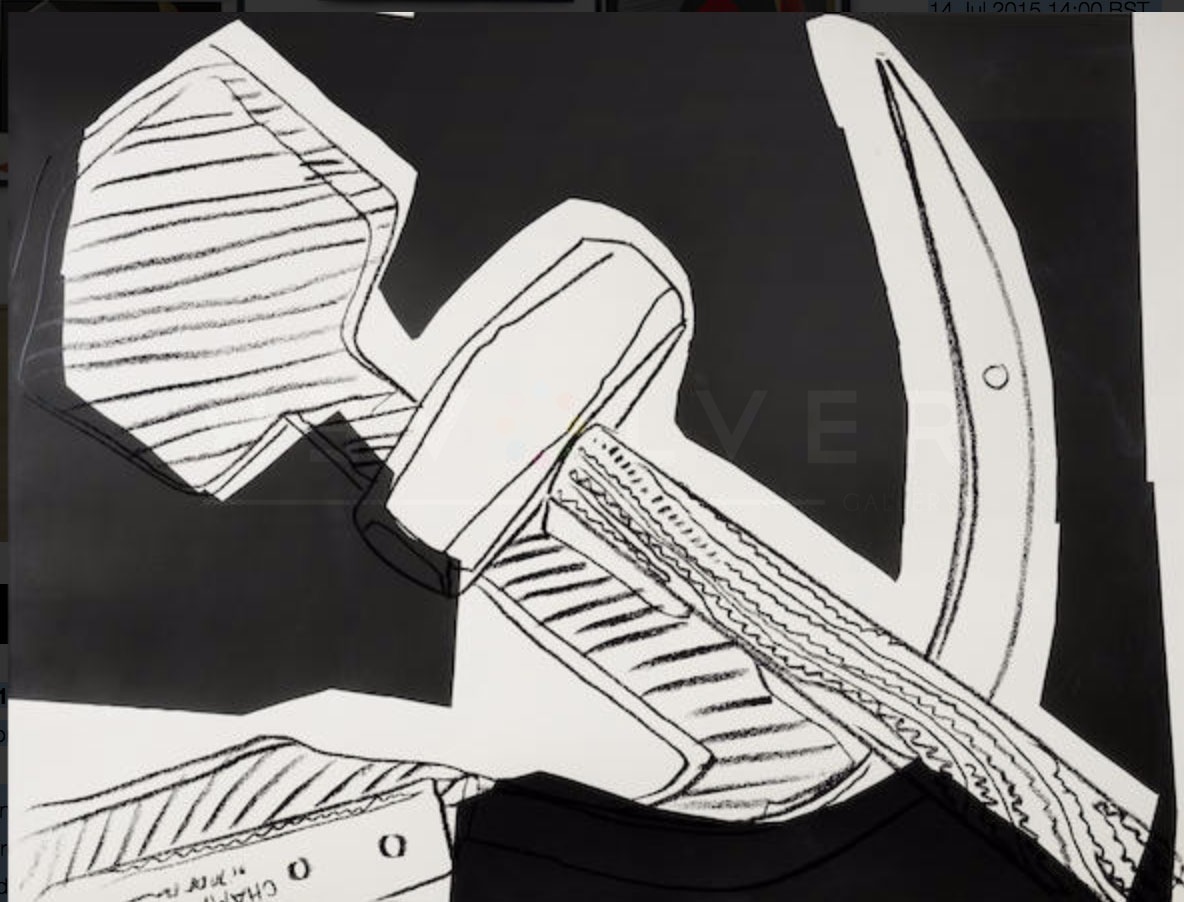

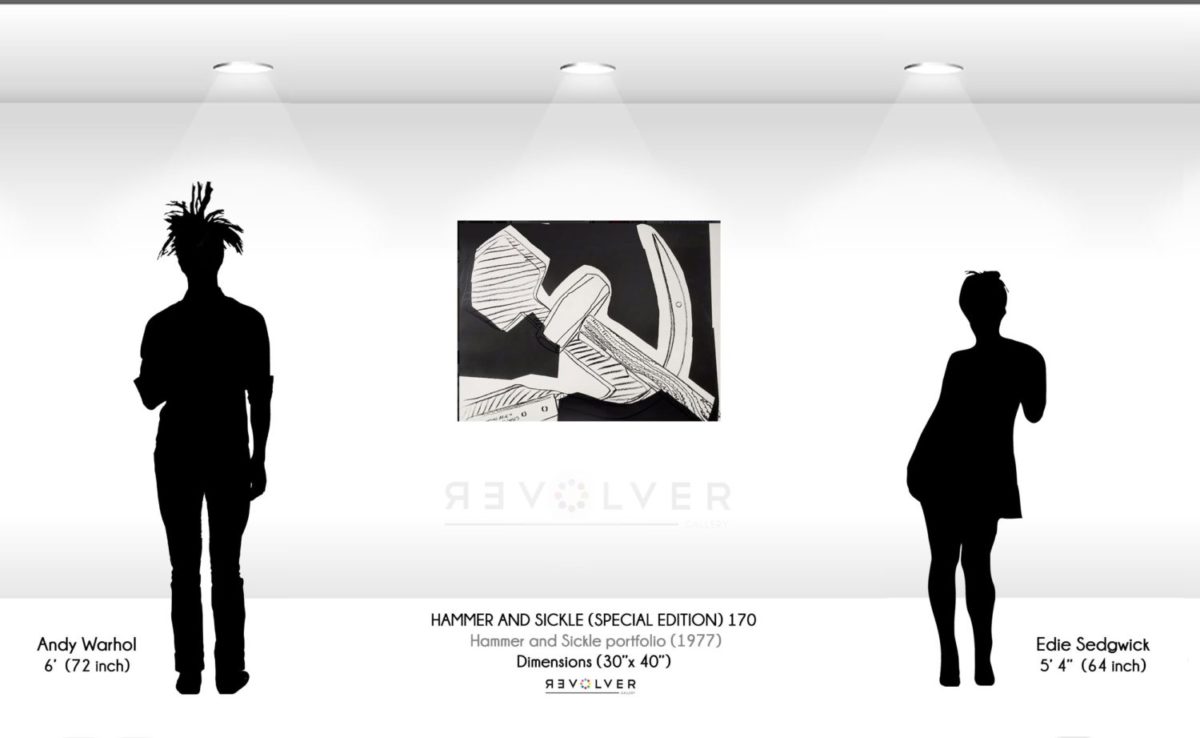

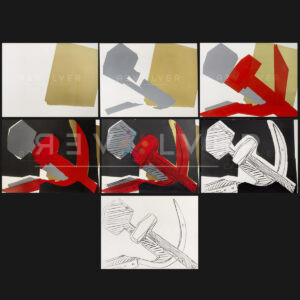

Warhol’s efforts to decontextualize the hammer and sickle are even more apparent in his Hammer and Sickle (Special Edition) portfolio. By illustrating the printing progression of Hammer and Sickle in the Special Edition portfolio, Warhol deconstructs both his artistic process and the symbol of the hammer and sickle itself. In Hammer and Sickle (Special Edition) 170, a sketch of the hammer and sickle appears outlined in black over a rough patch of white. The entire composition lies against a sponge-mopped black background. The background is inexact; in some areas, the black covers the sketched lines of the hammer and sickle, while in others, it leaves a thick white outline separate from the sketched boundaries. The black does not fully extend to all corners of the composition, leaving uneven stripes of white on the right and top sides of the print.

As the sixth print in the portfolio, 170 shows an incomplete version of the final print, depicted in 169. Hammer and Sickle (Special Edition) 165 through 168 each show the layering of color blocks in the screenprinting process. In 169, Warhol includes all color blocks and the sketching to show a complete composition. In 170 and 171, he deconstructs what he constructed, first taking out all color blocking aside from the black background in 170 and finally leaving just the sketch in 171.

In Hammer and Sickle (Special Edition) 170, Warhol demonstrates both the construction and deconstruction of the iconic symbol and successfully de-contextualizes the image. In this piece, Warhol reveals the fine line between art and propaganda and presents not a symbol of communism, but a simple screenprint of a hammer and sickle.

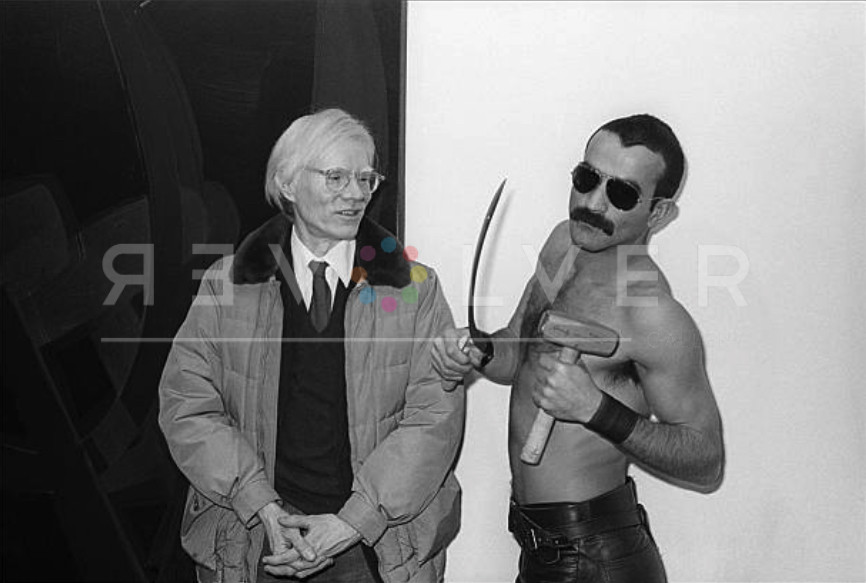

Photo credit: Andy Warhol poses with Victor Hugo, who holds the original hammer and sickle artist used in the works, at the opening of his “Hammer & Sickle” show at the Castelli Gallery, New York, New York, January 11, 1977. Photo by Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images.