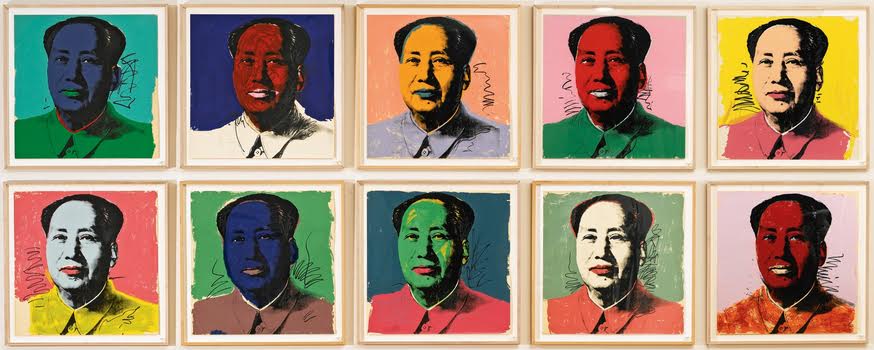

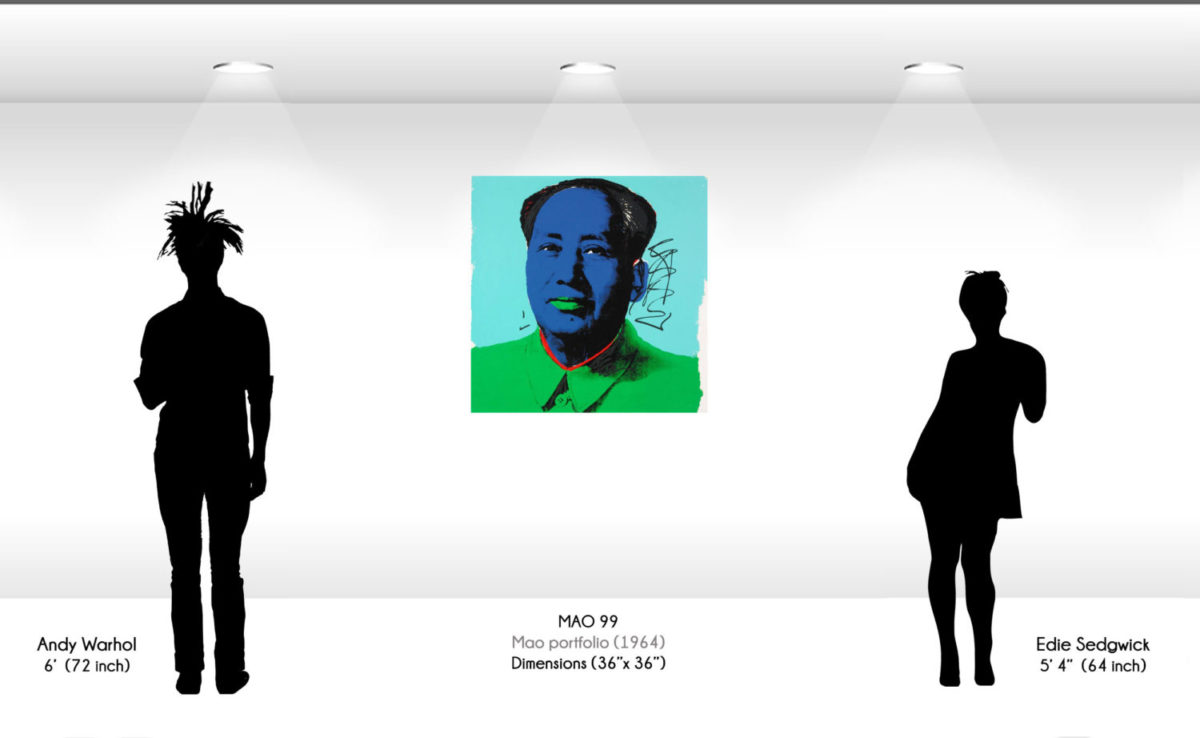

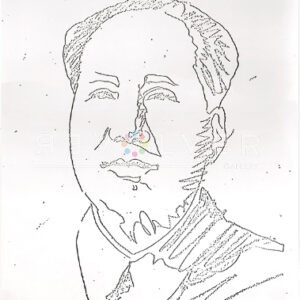

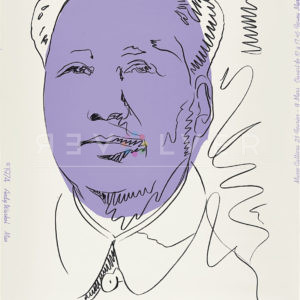

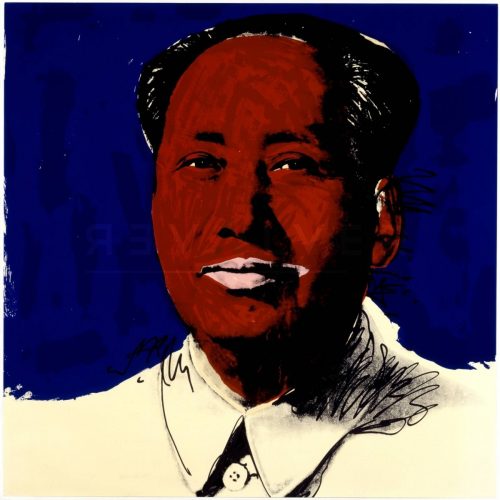

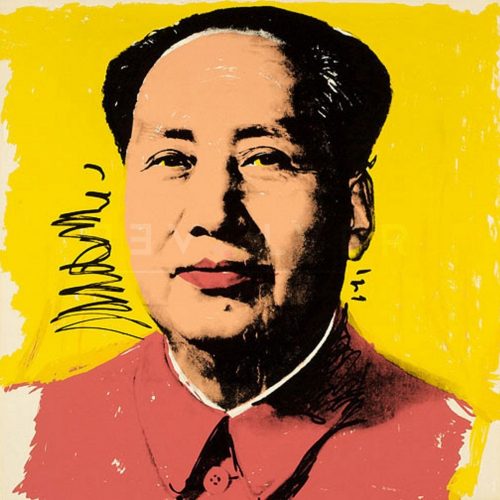

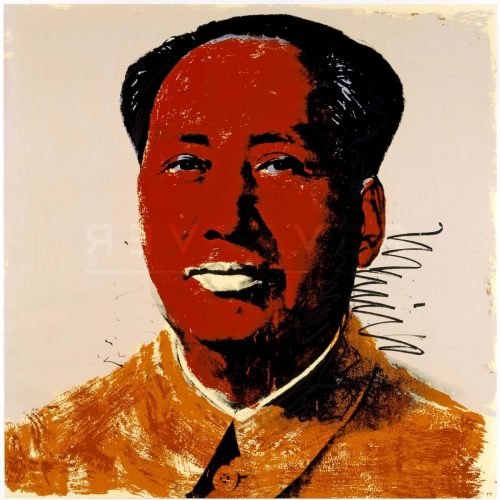

Mao 99 is a print by Andy Warhol included in his Mao portfolio from 1972. Mao 99 (sometimes called the “blue Mao”) and the the nine other silkscreen prints in the series are the culmination of Warhol’s interest in Chinese culture, specifically, Maosim. The prints represent a puzzle of two opposing political ideologies. However, a glaring synthesis between Chinese propaganda and Warhol’s silkscreen printing technique occurs in the repetition of images. Repetition is the most immediate principle in capturing the attention of the masses–and the massively reproduced works of Zedong and Warhol prove this.

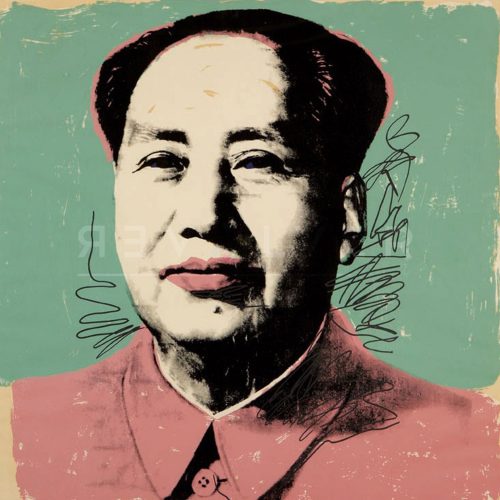

With this series, Warhol transgressed all of the strict and sacred depictions of the communist leader. Unsurprisingly, this caused a good bit of controversy at the time of publication in 1972. In Communist China, archetypal portrayals of Mao should remain serious and angelic, with warm hues. But, the Mao Portfolio transformed the former leader of the People’s Republic of China into a Pop-Art icon. Mao Zedong’s portrait from the cover of his Little Red Book was latent with the potential for artistic manipulation. The choice of imagery resulted in the removal of eight Mao prints from a worldwide retrospective of Warhol’s works after arriving in China in 2013. Chinese officials thought some people may confuse the colorization on Mao’s face with cosmetics.

The Mao Portfolio exposed the political side of Warhol, even though his formal position toward politics remained impartial. However, he did have interest in the political world, mainly as a part of his infatuation with famous people. His affinity for powerful figures shines through his work in portfolios such as Reigning Queens, Lenin, and Alexander the Great. The choice to depict Mao in a style akin to his famous celebrity prints suggests that Warhol wanted to capitalize on the Chairman’s politically charged aura. Just before the portfolio’s debut, the relevance of China in American media peaked. In 1972, Richard Nixon visited the global superpower in an attempt to foster diplomacy against the Soviet threat, inspiring Warhol to create the series.

Not even Warhol could outmatch the mass amount of Maoist iconography produced by the People’s Republic of China. Although, he didn’t need to. Instead, true to his ability to stylistically reintroduce ideas, people, and products back into the public sphere, Warhol created a metaphysical, visual art think-piece.

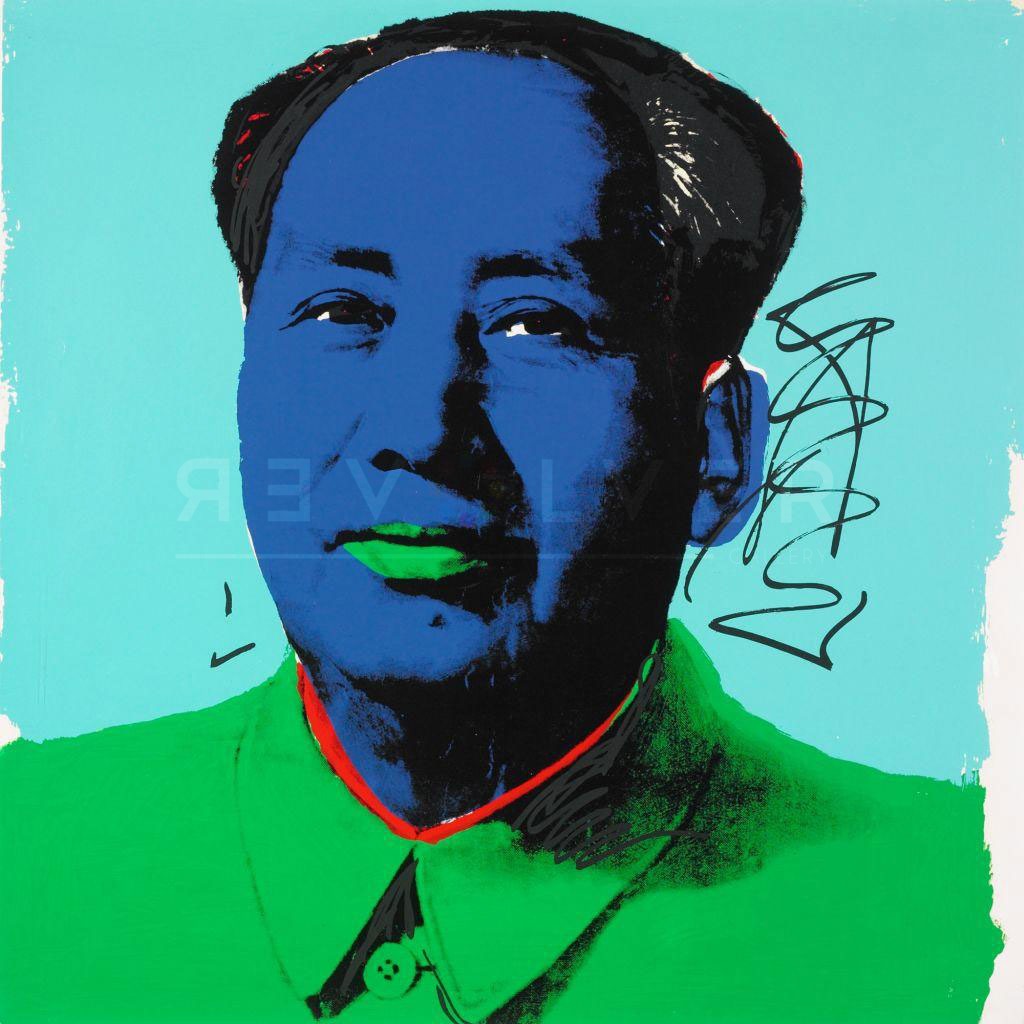

The contrast between the navy blue, bright green, and aqua background in Mao 99 makes for a lively composition. The vibrance of Mao’s green lips transforms his portrait into a fantasy. It is an impossible image; one that would stand 20 feet high if Disney were to reimagine Tiananmen Square. In 1982, Warhol gazed upon the equally famous portrait of Mao at the Tiananmen entrance to the Forbidden City.

The legacy of Mao is forever, by design. The art of designing is based upon organized structures, and Warhol had seized the means of artistic expression. Therefore, the construction of Mao’s god-like image (in the making since the 1940s) was already primed for the reconstruction that Warhol performed on him. Mao 99 is Warhol at his most clever, and his most political. Besides being highly controversial, the ultra famous portfolio is one of the artist’s most coveted creations.