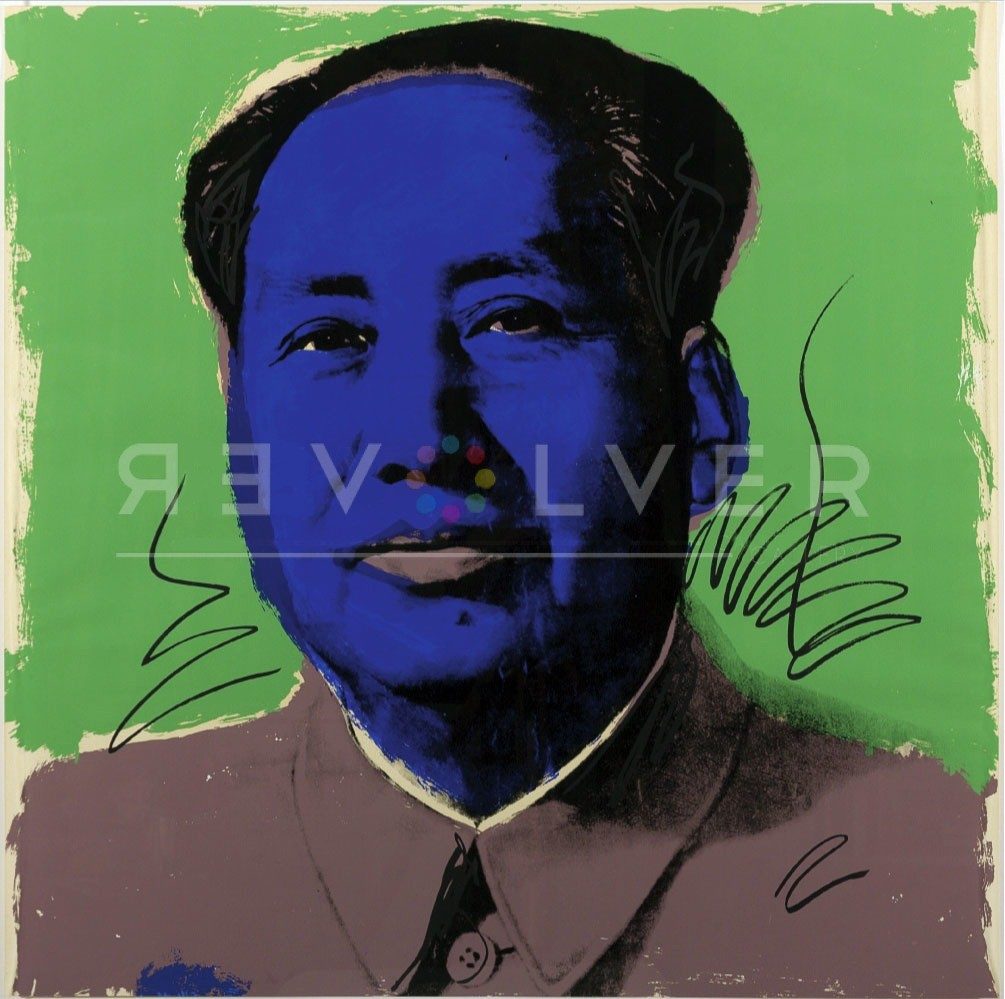

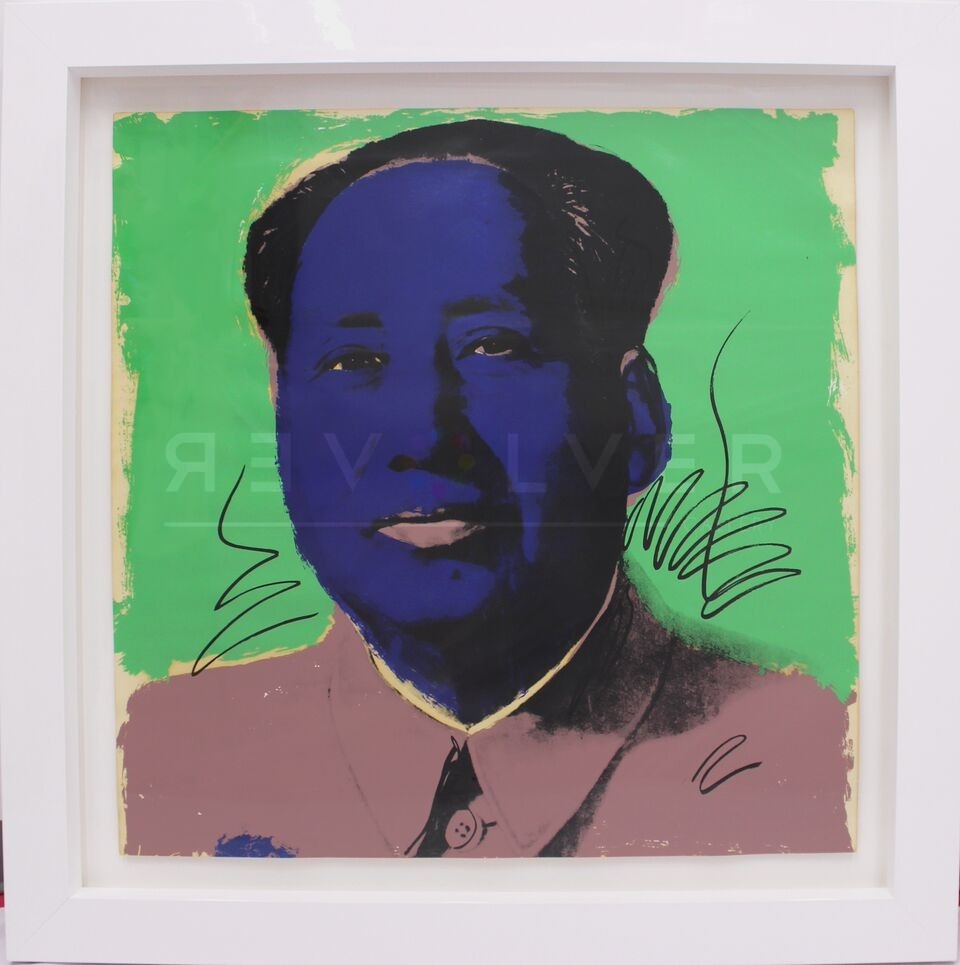

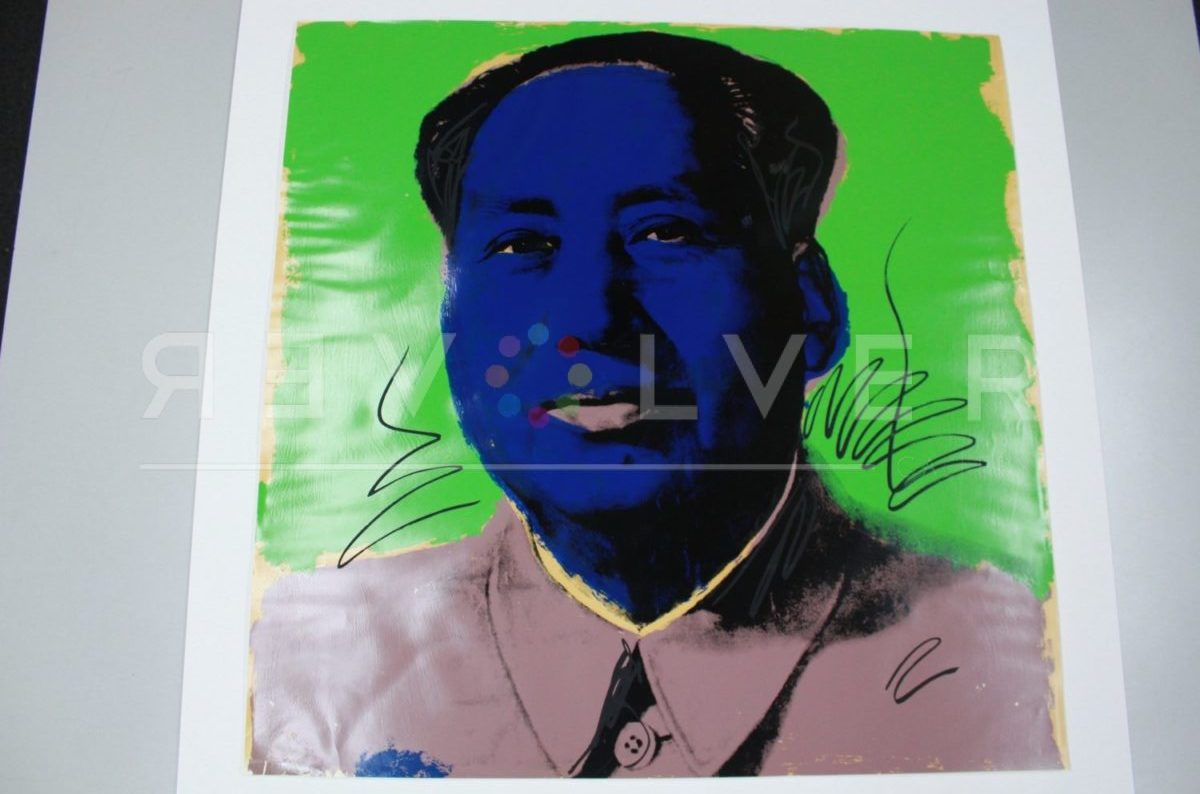

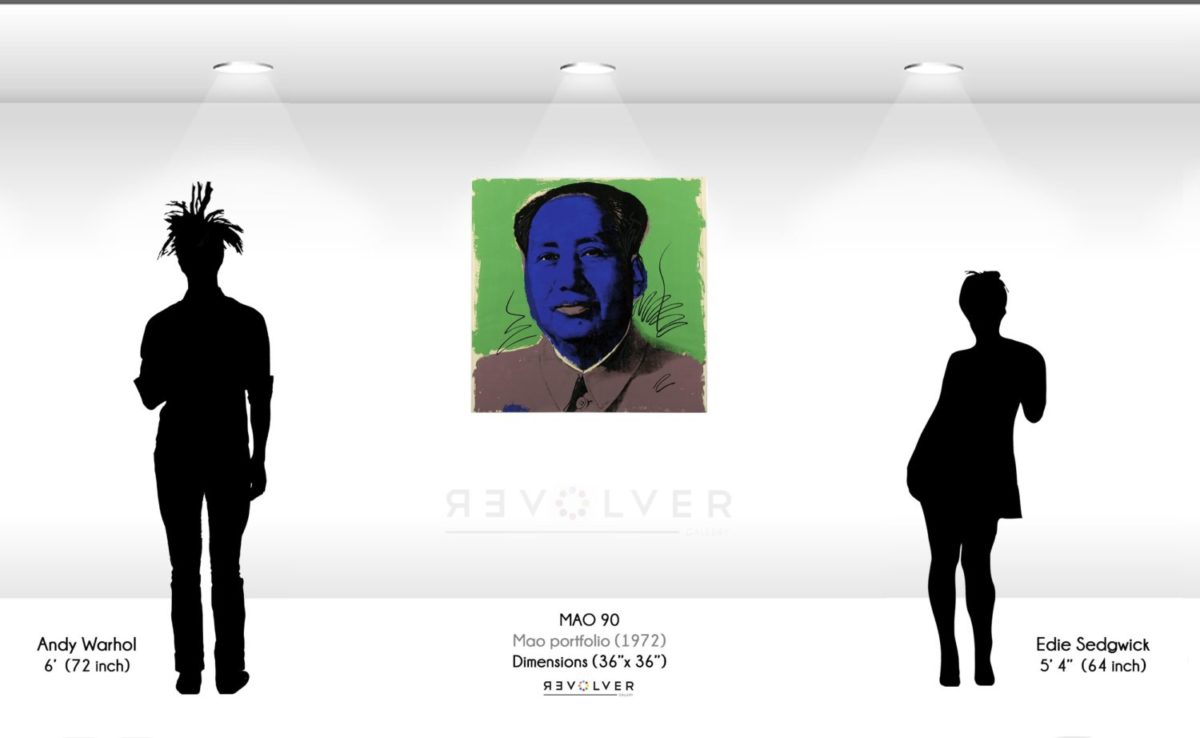

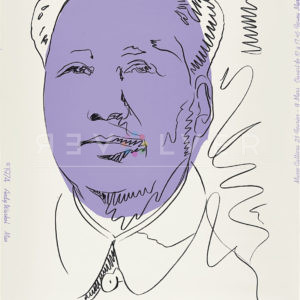

Mao 90 by Andy Warhol is a dazzling pop art portrait from the artist’s 1972 Mao series. It may be referred to as the “blue-green Mao,” or possibly the “blue Mao” in reference to the face alone. The portfolio is among some of Warhol’s most famous works of art, and is perhaps his most controversial. The Pop artist expanded beyond American culture in this 1972 collection, taking on a divisive political subject. Chairman Mao ruled China for nearly thirty years as a dictator, spawning the cult-like ideology known as Maoism. The concept intrigued Warhol, who was no stranger to mass appeal.

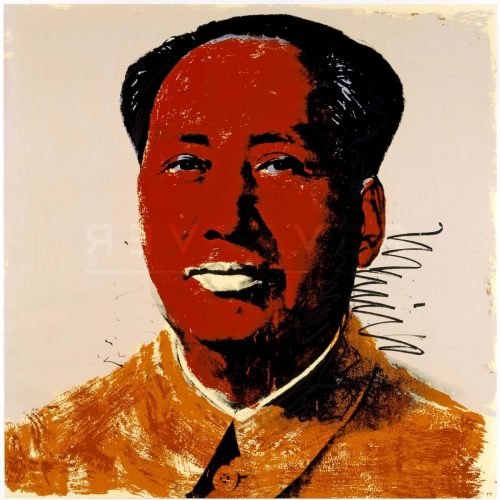

During the 1970’s Warhol completed numerous celebrity portraits including Mick Jagger, Muhammad Ali, and Truman Capote. It could be argued that the decade represents Warhol’s most political era. For instance, Warhol composed a damning screen print of Richard Nixon in the same year as Mao 90. He portrayed the then-presidential candidate with devilish orange eyes, scribbling “Vote McGovern” underneath the portrait. Though he chose to highlight Nixon as his subject, Warhol created the image for the McGovern campaign. It was the first direct political message in his art. Near the end of the ‘70s, Warhol would also portray President Jimmy Carter and explore communist symbols in his Hammer and Sickle series.

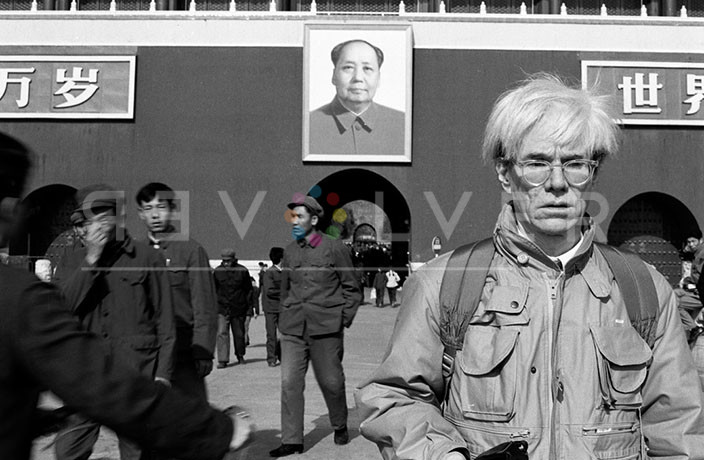

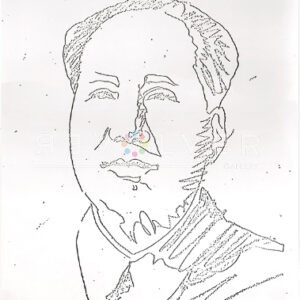

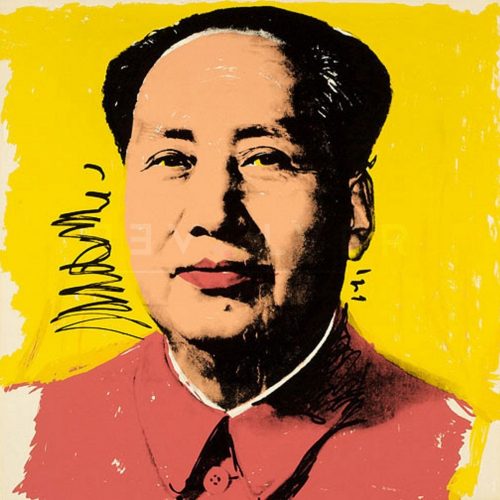

Mao 90 conveys a different kind of message, but one no less powerful. In this portrait Warhol splashes Mao with electric blue and bright green hues, his brush strokes frantic and disordered. The loud colors clash against the very nature of life under communist China. “I’ve been reading so much about China,” Warhol stated. “They don’t believe in creativity. The only picture they ever have is of Mao Zedong. It’s great. It looks like a silkscreen.” Warhol was utterly American in his love for capitalism and consumer culture. While the communist country’s condemnation of individualistic artwork outside the realm of state-approved propaganda baffled him, Warhol was also awed by Mao’s iconography. The culture relied on repetitive, mass-produced images of the ruler, making him something of a star.

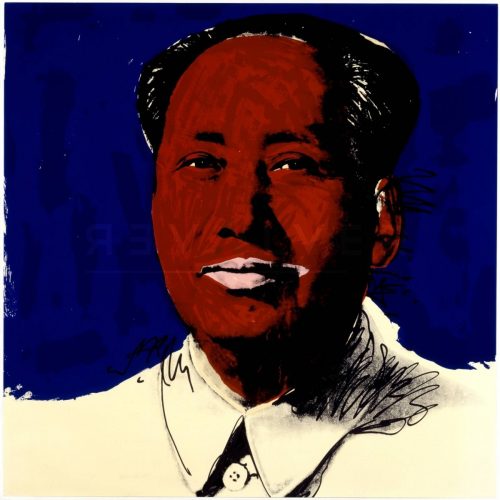

By placing Mao through the lens of Pop, Warhol mashed together two opposing cultures. Yet in doing so, he displayed their uncanny similarities. The Mao series leads the viewer to wonder if America’s worship of celebrity idols is so different than fanatical support for political leaders and vice versa. Furthermore, in the collection Warhol explores both Mao’s international fame through the historical context of the Cold War and his anti-individualistic worldview. In giving Mao the same Pop art treatment as Mick Jagger or Muhammad Ali, he personalizes the leader and challenges his strongman image. Warhol suggests that ultimately, Mao is an icon who succeeded in selling an idea to the masses.

Mao 90 and the rest of the prints in this collection subvert the relationship between art and political propaganda. In addition, Warhol’s Pop take on politics gave new meaning to his work, allowing him to expand beyond American culture and create art on a grander scale. Art dealer Bruno Bischofberger suggested that Warhol stretch his ambitions by focusing on the greatest figures of the modern age, and the artist went several steps further. Moreover, Warhol’s efforts outlasted the political climate of his time. In 2013, China banned the pieces from appearing in a Warhol retrospective due to Mao’s embellished appearance. Mao 90 and similar works remain thought-provoking to this day.