By Mia McLaughlin and Mason Rogers

Andy Warhol is remembered as the Prince of Pop Art, and he is especially praised for his classic and most well known works, such as the Campbell’s Soup Cans and his Marilyn portraits. While many of his Pop Art masterpieces carry themes of beauty and glamor, they also retain a neutral objectivity, by which Warhol removes any trace of himself from the final product. However, if we look back at the nascent stage of Warhol’s career, much of his earlier work deviates in style and method from the images that would make him famous. Moreover, this early work reflects a young Warhol who had not yet abandoned his personality in the art-making process.

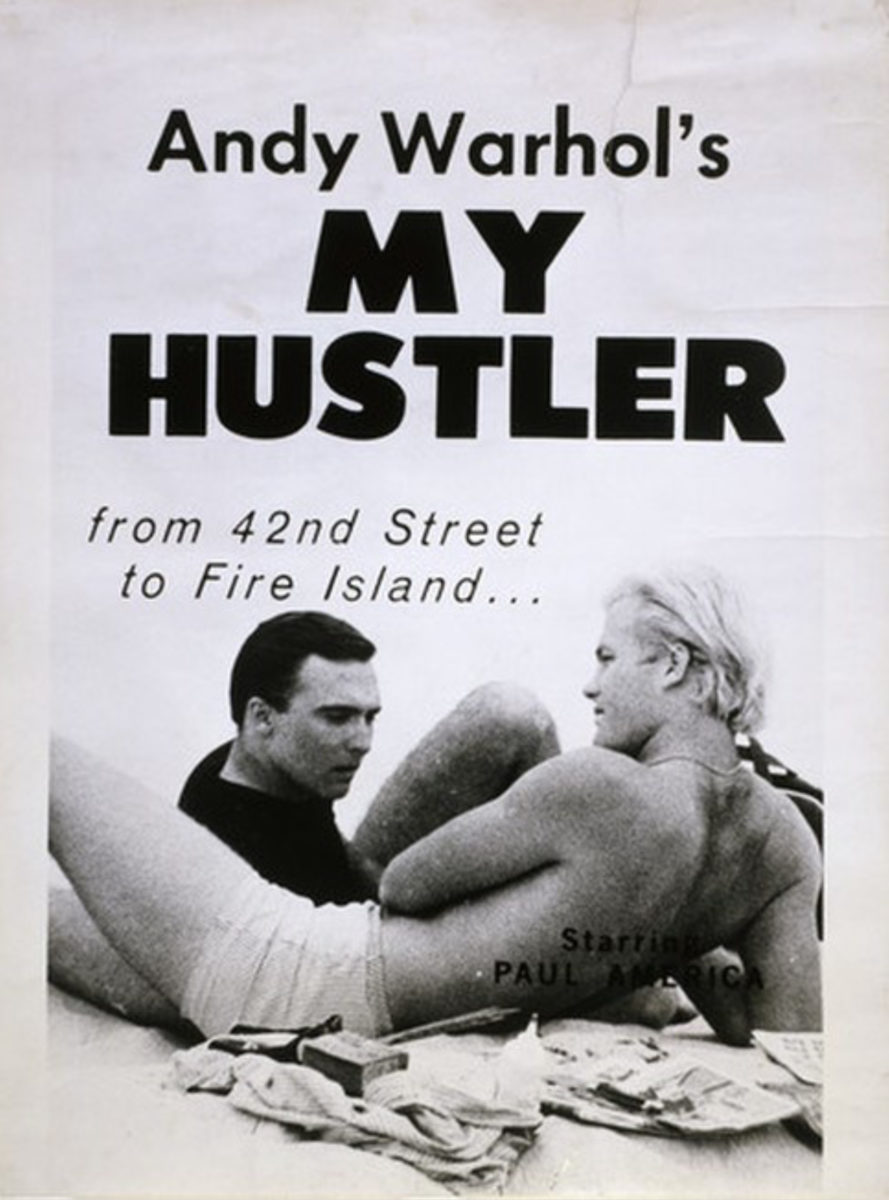

Andy Warhol created several homoerotic sketches in the 1950s. When he began to gain footing in the art world, he submitted multiple works to a fine art gallery. Gallery owners rejected him many times because his work, showing homoerotic drawings of nude men, was considered “too gay.” In the socially conservative environment of the 50s, Warhol’s drawings were far too taboo. But, regardless of his society’s response to homosexuality, his gay identity never truly vanished from his work.

The bulk of Warhol’s homoerotic drawings from the 1950’s are sparsely recognized today. In his early 20s, Warhol created works such as Studies for a Boy Book, Seated Male Nude, Standing Male Nude Torso, Male Nude Lower Torso and Male Couple. In contrast to the bulk of his oeuvre, each of these works contains explicit content that speaks to who Warhol was as a person. It immediately becomes evident that Warhol’s sexuality heavily influenced his artistic output. He seems to be preoccupied with this realm of his personality; this contrasts with his many later claims, in which he expresses his disinterest in sex, love, and dating, and even indicating himself to be a virgin at the age of 52, in an interview from 1980.

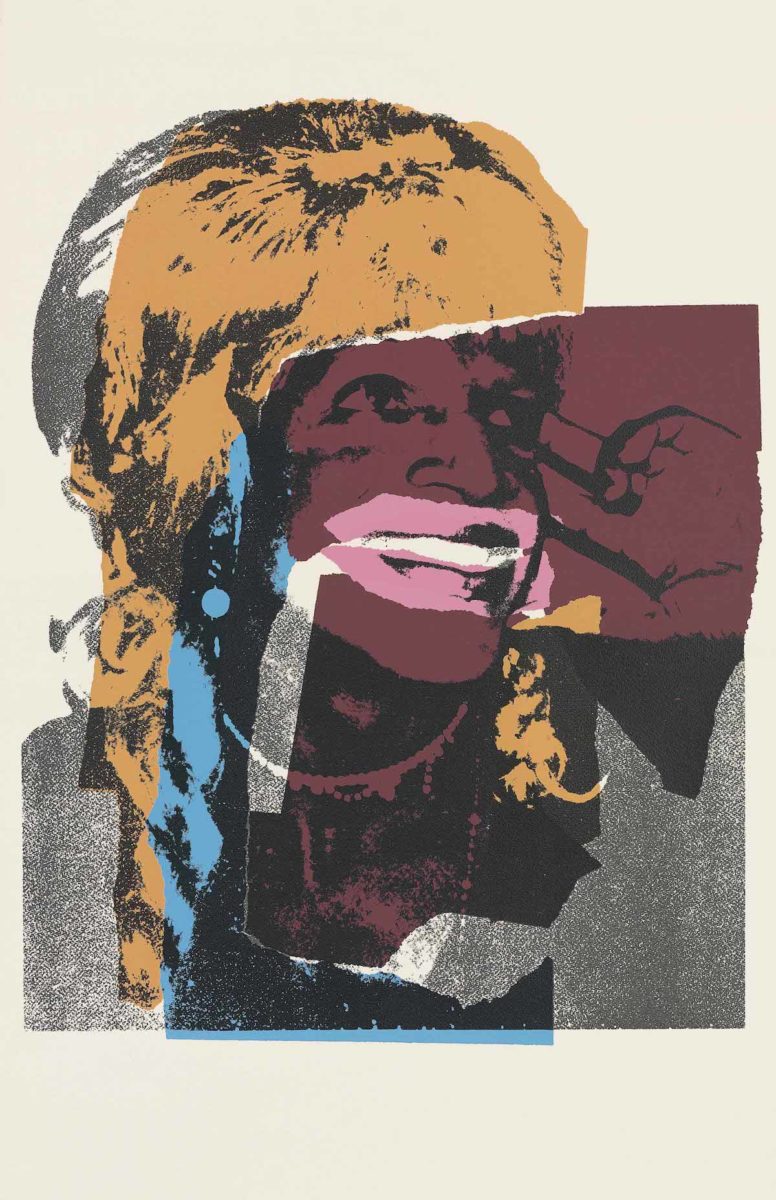

After the release of these films, Warhol allowed his gay identity to be shown in his paintings and photography. In 1975, at the suggestion of Italian art dealer Luciano Anselmino, Warhol released his incredibly successful Ladies and Gentlemen series. The portfolio featured trans women and drag queens from a New York City nightclub called The Gilded Grape. With the help of Bob Colacello and Ronnie Cutrone, who recruited the drag queens from the club, Warhol photographed several models for the series. He took over 500 Polaroid photographs of the club’s patrons, which he would later use to create the portfolio of silkscreen prints.

After the chaos of the Stonewall Riots, in 1970, Johnson and her friend Sylvia Rivera founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), a radical political collective and activist group. STAR helped queer youth and sex workers by providing housing and other support. The same year she founded STAR, Johnson also helped initiate the first Gay Pride Parade. In August 2020, it was announced that a statue of the revolutionary queer icon would be erected in her hometown of Elizabeth, New Jersey. Even though Warhol didn’t show much of an interest in Johnson aside from creating her portrait, he consequently increased awareness of her struggles and tireless work for the queer youth in the United States.

Later on, Warhol presented his own try at drag. In the 1980s, Warhol took several polaroids of himself dressed in drag that are known as Self-Portrait in Drag. Warhol was also known to sometimes dress in drag while attending parties. He wrote in his diary about deciding what to wear to a party in 1978:

“I had to think about what drag to go in to Halston’s party later on, so I sent Robyn out for a wig and he came back with the perfect one—a grey Dolly Parton ($20.51), and I put it on and wore the dress I’d once designed for a Rizzoli art fashion show that was six different designers’ dresses all sewn together.”

Two years after the publication of Ladies and Gentlemen, Warhol began working on two new series called Torsos andSex Parts. Ostensibly, this began after a stranger bragged to Warhol about the size of his penis, to which Warhol responded by taking out his Polaroid and snapping a few pictures. He took these photos and put them in a box labeled Sex Parts. Later that same year, he rediscovered the images, inspiring him to create new works based on the photographs.

For Sex Parts, Warhol produced a series of photographs of male (and some female) models from gay bathhouses and nightclubs (recruited by Victor Hugo). He took close up shots to specifically highlight genitalia and the contours of the human body. Many of the images are highly explicit, allowing the series to test the line between pornography and fine art photography. While similar, his Torsos series is tamer, but maintains a focus on the nude male body, often coming close to the X-rated material in Sex Parts. Warhol also used some of these photographs to create screen prints, such as Torso (Double) (1982), seen below.

These series can be seen as a final affirmation of Andy Warhol’s sexuality, and a possible return to the more “free-spirited,” personal content of some of his work before fame. In the execution and publication of these series, Warhol finds a powerful way to accept, express, and come to terms with his sexual identity. Warhol’s strong Catholic faith was likely a source of his internal struggle, but only alongside other factors in the cultural milieu of his upbringing (reportedly, Warhol used to joke about how Catholics aren’t allowed to be gay). It is fascinating to follow the Warhol timeline while considering his sexuality. One can see how it ebbs and flows in and out of his projects. There is a clear climax in the mid to late 1970s, where Warhol addresses this sector of his personality directly. At the same time, this affirmation passes subtly under the shadow of his greater works of the decade, noticed primarily by those who study Warhol closely.

As for sex itself, in the end, we might never know Warhol’s true opinion on the subject. He was undeniably drawn to the concept, yet he often described it as “boring,” or as demanding too much effort—as something he’d prefer to live without. Perhaps Warhol’s artistic forays into sex are no more significant than his other themes, all a part of his greater wish to document the symbols, artifacts, and human activity of his time. This proposition gives no special consideration to the subject of sex in Warhol’s work, and implies that sex was just one star in a massive constellation of culture that propelled him to replicate his surroundings.

Sex is more exciting on the screen and between the pages than between the sheets anyway. Let the kids read about it and look forward to it, and then right before they’re going to get the reality, break the news to them that they’ve already had the most exciting part, that it’s behind them already.

—Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again), 1975.