By Dylan Henricksen

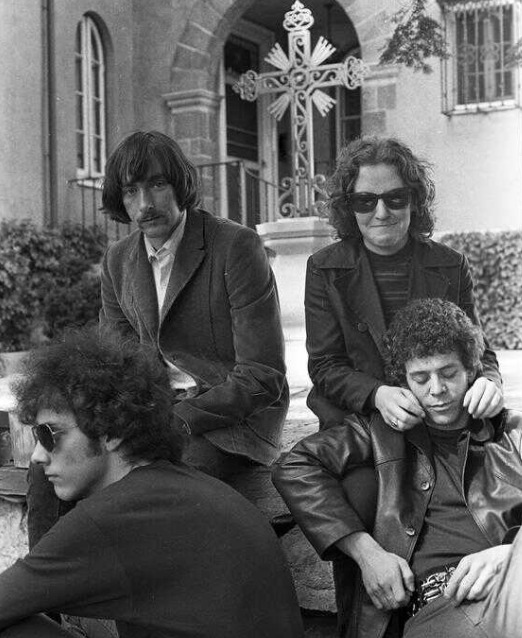

In 1969, Albertson not only followed the VU onto the sacred living quarters of Episcopalian monks (known for their radical hospitality), but into a pivotal time for the band. Their third self-titled album had just been released with the help of Steve Sesnick, their new band manager, and manager of the Boston Tea Party––a Boston nightclub that concentrated the blossoming musical talents of underground and psychedelic rock bands alike. The V.U.’s residency at the 53 Berkeley Street locale of the Tea Party had reached its climax in 69’, evidenced by the massive light show being eclipsed by the band on stage in the photos by Albertson. At a glance, the photos can be easily mistaken for Andy Warhol’s dazzling light show extravaganza, called the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, that he put together for the band while he was their producer and manager from 1966 to 1967.

The Boston Tea Party location had already harnessed a captivating aura before the existence of the nightclub, which would go on to host bands such as the Grateful Dead, the Sun Ra Arkestra, and MC5. The building previously acted as a branch of the Film-Makers Cinematheque, run by the godfather of avant-garde cinema, and Lithuanian-American filmmaker, Jonas Mekas. The Cinematheque embraced the obscure, screening almost anything sent to them. Among the underground filmmakers who had their movies screened at the constantly shifting locales was Andy Warhol. The formation of the Cinematheque took place in 1964, and Warhol’s “News Reel” would be the first presentation on the opening night. It would not be until 1967 when Warhol’s films would begin to be shown at the Boston location of the Cinematheque, the same year of its transition into the Boston Tea Party nightclub.

Between the years of 1965 and 66, Warhol had given up painting to pursue what would be considered a combination of the arts. Having seized the means to artistic expression, the next natural step in Warhol’s craft would be to animate the world around him in the same way his paintings did. His connection with the Cinematheque and Mekas gave him a variety of places to experiment with lights, film, and sound. The art world in New York City at the time was imploding with untamed talent, and everyone was ready to make something happen with their art. In his co-created 1967 book The Medium Is The Message: An Inventory of Effects, Canadian communication theorist Marshall McLuhan captures the ephemeral energy given off in 66’:

“Electric circuitry has overthrown the regime of ‘time’ and ‘space’ and pours upon us instantly and continuously the concerns of all other men. It has reconstituted dialogue on a global scale. Its message is Total Change, ending psychic social economic and political parochialism.”

Free energy was radiating between every soul in New York City, it just had to be creatively redirected into the makers of Total Change.

Then Warhol met The Velvets at the Cafe Bizarre shortly after failing to create a band of his own–the final sonically charged component needed in the merging of the arts. After meeting Andy mere days before being kicked out of the Bizarre for playing “Black Angels Death Song” one too many times, Lou Reed remembers what would become the moment that he knew what Andy was doing with the arts was serious:

“Andy told me that what we were doing with music was the same thing he was doing with painting and writing, i.e., not kidding around. To my mind nobody in music was doing anything that even approximated the real thing, with the exception of us. We were doing a specific thing that was very, very real. It wasn’t slick or a lie in any conceivable way, which was the only way we could work with him. Because the first thing I liked about Andy was that he was very real.”

The first incarnation of Warhol’s multimedia happening was called Andy Warhol, Uptight, and was given a week-long residency at the Cinematheque on 41st Street. Barbara Rubin, filmmaker and counterculture pioneer, pitched the mixed-media idea to Warhol, who did more to publicize and fund the event rather than orchestrate it. Just like at the Factory, many people were involved in helping Warhol maintain his totalizing multimedia happening. The lights were manned by Danny Williams, the music by the Velvet Underground and Nico, slides and film projections by Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey, Billy Linich and Nat Finkelstein took photographs, and Barabra Rubin worked the movie cameras. Rubin was also the person responsible for introducing Andy to The Velvets.

The entire production was based around agitating the audience into a state of bewilderment until all of time and space collapsed onto the scene–the needed combination of lights, sound, and vision that was the result of Total Change. Gerald Malanga, Warhol’s adaptive assistant, recalls the mood: “Uptight meant interesting. Uptight meant something, as opposed to the perennial nothing would happen.” After the heat emitted by Uptight became too hot for the Cinematheque, the amphetamine-fueled entourage were already booked at a film series at Rutgers University, New Jersey, and at the University of Michigan Film Festival. Both shows delivered the intended effect of “leav[ing] them with wanting less,” as was the policy Warhol worked under.

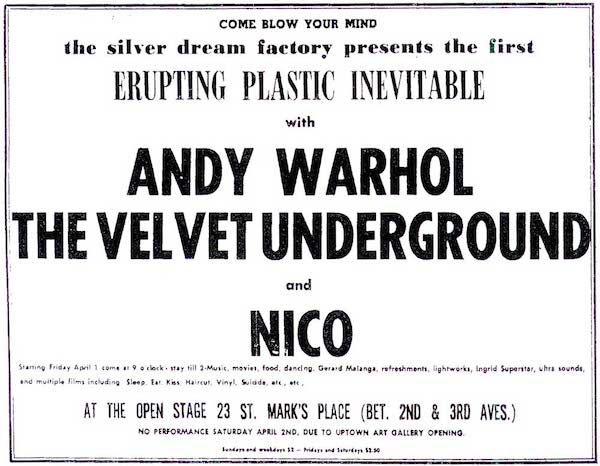

After a few Vox equipment deals, and a month-long lease signed in April of 1966 for a place to present the show on St. Mark’s Place, Uptight would then be called the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. The title was coined after Malanga and Rubin scanned the backside of Bob Dylan’s album “Bringing It All Back Home” and landed upon Dylan’s stream of consciousness liner notes, out of which came the title. The new show space would be called the Dom, and what followed was what Jonas Mekas described in the Village Voice newspaper as:

“The most violent, loudest and most dynamic exploration platform for [Intermedia shows]. Theirs remains the most dramatic expression of the contemporary generation. The place where its needs and desperations are most dramatically split open. At the Plastic Inevitable it is all Here and Now and the Future.”

What was the E.P.I experience like at the Dom?

Well, first you had to hear about it. The show was advertised through an ad in the Village Voice newspaper, the first alternative newsweekly in the U.S. Upon arriving at the Dom, one would quickly find out that the show was actually being held above the Polski Dom Narodowy, or Polish National House. “The Dom” stuck as a recognizable moniker for the show’s locale but instead premiered in the second story hall called the Open Stage, run by “Bob” John Liikala.

When entering the floor of the hall there is a faint buzz made up of the whirling fans of the projectors. The lights dim, the four band members walk out on stage, and a single discordant chord is struck, signalling to everyone involved in the production to conglomerate onto the next wave of sound being pulsed out of the Velvets amps. Any number of Warhol’s films are being projected on either side of the stage. Colored slides are being alternated into spotlights, and each overlapping light fuses and falls away in a dance of colored circles. While cracking a whip, Gerald Malanga oscillates to the intoxicating drone of John Cale’s viola. Ingrid Superstar lies on the floor before she simulates taking a dose of heroin, and rises from the ground like Odette from Black Swan. The cacophony of all the individual moving parts persists, and it is now up to you to synthesize it all into a meaningful moment, or else put up your defences until it’s over.

The inclusion of Warhol’s influence in the evolving history of the Boston Tea Party building would come to an end when the Velvet Underground arrived on May 26th, 1967, following an incident at Steve Paul’s The Scene venue when the audience came onto the stage with the E.P.I. performers. An incident that would foreshadow the end of the E.P.I, thus leaving the Velvet Underground to play without Warhol’s entourage for the first time in May at the Boston Tea Party. Ronnie Cutrone, pop artist and dancer for the E.P.I recounts the moment he knew Warhol’s ambitious combination of the arts would be no more:

“When we played at the Scene I remember Gerard, Mary and I were dancing and the audience came on stage with us and totally took over. Mary and I looked at each other and had this look on our faces. It was half desperation-half relief that finally everybody was part of it… Everybody became part of The E.P.I. It was a bit sad, because we couldn’t keep our glory on stage, but we were liberated to be as sick as we were acting! From that standpoint it was interesting socially that it happened that way.”