And it paints quite a picture…

By Reagan Carraway

What is art’s true purpose? The question has been up for debate for goodness-knows-how-long, but four-time Oscar nominated writer Anthony McCarten’s The Collaboration seems to definitively answer the question.

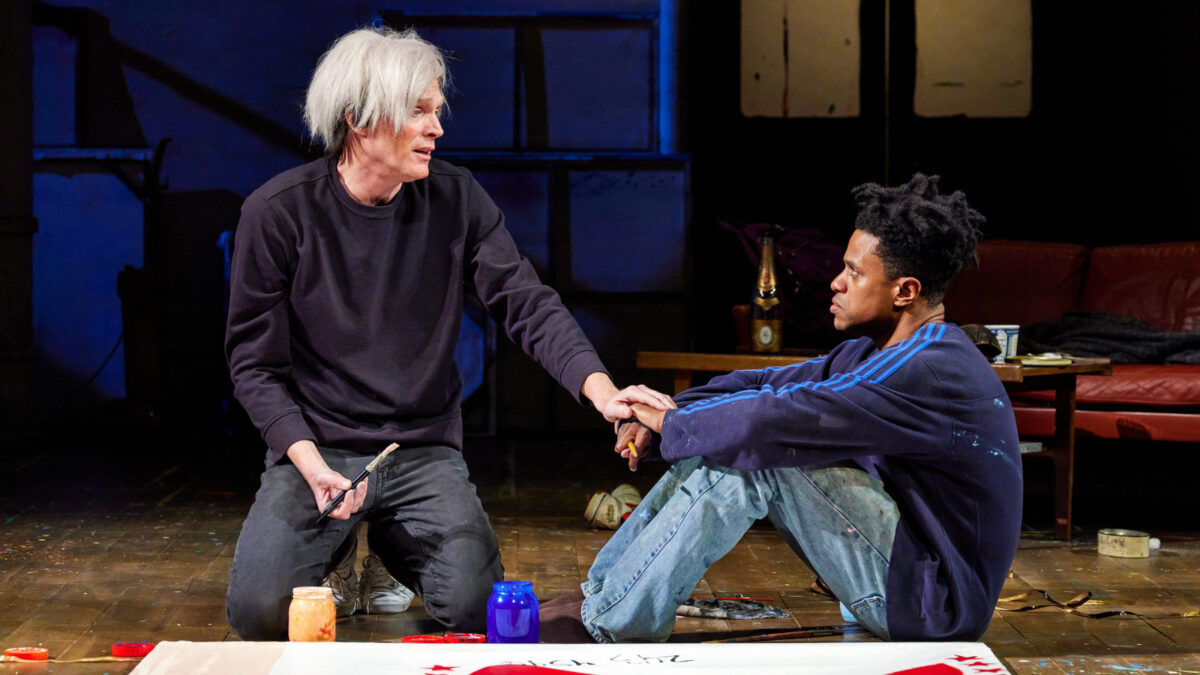

The play, which took the Samuel J. Friedman stage this holiday season, breathes life back into modern artists Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat to tell a story of their real-life artistic collaboration of 1984. Starring Paul Bettany (Wandavision) as Warhol and Jeremy Pope (Choir Boy) as Basquiat, it navigates the complicated evolution of their strangers-to-friends situationship and the in-betweens of ego, grief, addiction, race, religion… and coming back to life.

At open, the audience is dropped directly into the gallery of Swiss art dealer and mutual agent of Basquiat and Warhol, Bruno Bischofberger. He is pulling at strings to facilitate a painting partnership between the two artists to create a gross net the likes of which have never been seen, despite their biases against the other’s style and philosophy: Warhol is an ever-loving commercial artist whose love of painting was lost long ago, and Basquiat is a painter of great purpose who is adamant that commercial art fuels corporate evil. The first few scenes are a liberal summary of actual events when Basquiat and Warhol initially met in a casual lunch setting with Bischofberger. Erik Jensen’s comedic mastery as Bischofberger manages to shape the play-by-play dialogue, no doubt illuminated by Kwame Kwei-Armah’s direction which acts like a captain to McCarten’s ship. “Painters are like boxers. They both smear their blood on the canvas,” Bischofberger says in a line attempting to pay homage to the 1985 ad featuring Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol in boxing gloves for their Shafrazi gallery exhibition. It’s a fitting set-up for what turns into a two-hour verbal boxing match between the two opponents, and it’s true – blood and paint are smeared.

The Collaboration’s genetic makeup is at-large a conglomeration of quotes from The Andy Warhol Diaries and as much that’s known of the relationship with some creative interpretation to spare. But it doesn’t matter. From its pre-show, The Collaboration is a multimedia production that would make Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable proud, opening with a live DJ and a light projection show that dives into a story in such a way that, even for those who know it, feels totally unpredictable. Intermission presents a fast-forward abetted by stunning black-and-white montages projected onto the walls of the theater: Bettany and Pope as the artists ride a bike, paint, laugh, and rollerblade together. Decorated with little more than a piece of furniture and the art in progress, the set build holds a barren glory that gives vintage warehouse glamour and is easily transformational between the play’s three locations. Costumes and WAM hit the nail on the head for specificity (and nothing is more delightful than seeing Warhol in a white leather jacket with Basquiat’s face on it). Bettany films Pope with a vintage video camera as Pope paints in real time– his first look into the lens is nothing short of breathtaking (two seats down, a woman whispers “goosebumps”). It is projected onto the walls, eyes and an angelic smile revealing a striking vulnerability and boyishness in Basquiat that makes the sprint to an end laced with drug relapses, breakdowns, soul-whipping honesty, death, and hugs that encompass all that love is, absolutely earth-shattering. The Collaboration is nothing short of a visual masterpiece and we should expect nothing less from a play about two of the most prominent artists to date.

The first time we see Bettany as Warhol, applause erupts. He wears something directly out of a vintage Warhol photo, camera hanging ‘round his neck. At the end of the scene a FLASH of his camera at the audience and we’re suspended in a moment of wondering whether this photo will join the collection of his immortalized polaroids. His chic roboticism, calculative movement, and selective speech keep a steady heartbeat to the play but his vacancy shows us what he tells us later: he is fundamentally afraid of truly living. Pope’s Basquiat is beautiful and youthful, and enters in a cloud of smoke. He exists as a burning force of energy, a fusion of idealism, intelligence, anger, endearing boyishness, and a crippling fear of impermanence that remind us he has seen too much at his young age. Pope’s physical and vocal musicality beautifully contrast Bettany’s clinically Warholian polite-isms as they in their respective characters butt heads in pace (with sensual undertones reflective of the long-standing curiosity of the full complexion of the artists’ relationship). To top it, the actors are in sync, and their mutual trust is evident not only in their seamless transition into the second act’s dense material, but in their affectionate embrace during their standing ovation.

The second act engenders a feeling of being swallowed by quicksand: slow and forceful and lands you in a very dark place. Without the poignance of a heart-wrenching scene in which Basquiat and Warhol stand half-naked in solidarity, bearing scars—Warhol from a 1968 assassination attempt and Basquiat from being hit by a car as a young child—it may be impossible to make it through the act without suffocating from sadness.

Pulling off an entrance that would challenge any actor, Krysta Rodriguez enters as Maya, Basquiat’s on-again-off-again girlfriend. This feels like the last time we’ll laugh without crying, though it is a dark comedy she and Bettany play in, and her already brief time onstage is cut short by a horrific tragedy that would kill something in Basquiat and plunge him deeper into his heroin addiction and an obsession with painting a work with enough “magic” to save his loved ones from death. When Warhol’s filming “steals the spirit of the painting” and its power fails to undo the tragedy, their friendship nearly crumbles in an argument that digs into the ugly parts of both artists, played with nuance and care by both Pope and Bettany. A moment of truth salvages the relationship for now, but the impending mortality of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol hangs in the rafters of the theatre, making an already tear-jerking ending that much heavier.

“Next time you die, Andy, I’m going to bring you back to life.”

“But you already brought me back to life, Jean.”

This last exchange is the heart of the play. One man afraid to live, the other to die, both with seemingly impossible differences, who came together for a collaboration that was initially a bust. Their journey together brought them back to life, if only for a little while, and 30 years after their deaths, their lives and art have done the same for countless others. That is art’s purpose.