Justice Jackson | January 2018

Andy Warhol has appeared in countless Hollywood films over the past few decades. Well, maybe not the artist himself, but there have been many representations of him. From Crispin Glover in The Doors (1991) to Bill Hader in Men in Black 3 (2012), Warhol has lived on in Hollywood films for decades. However, what you may not have known is that far before any of these films were ever conceived, Warhol was busy making his own, many of which most people have never seen, let alone ever heard of. They drifted far into the realm of the avant-garde, but had much to say about traditional filmmaking.

Warhol’s films were not the type you would watch with popcorn in your local theater. In fact, they were so far into the avant-garde that they are considered anti-film. In the early 60’s, Warhol created films such as: Eat (1963), Kiss (1963), Haircut (1963), and Sleep (1964); Sleep, for example, is five hours and twenty-one minutes of his friend John Giorno sleeping. It would have minute changes every once in a while, things to remind you that it is indeed a film. Some of these would be actions from Warhol, like a camera zoom, but many of these changes would come from the person that Warhol was recording, like Giorno’s movements while asleep. In this way, it is as if Warhol was giving all the control to the actors and allowing them to dictate the way the film would play out. This is an interesting notion, as in a typical film the director is the one with the most control and the actor has possibly the least, but it was just one of many ways Warhol subverted the medium through his work with film.

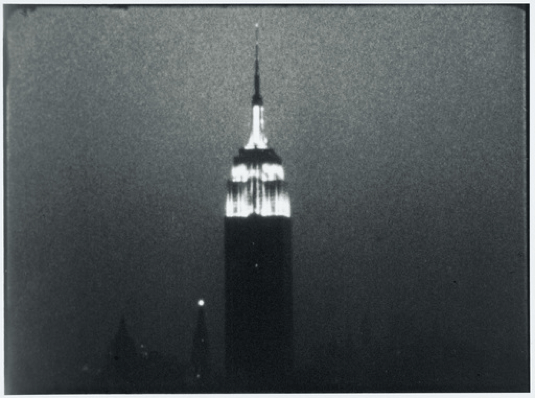

Another Warhol film, Empire (1965), has a runtime slightly over eight hours and consists of nothing but a shot of the Empire State Building. Next to Sleep, Empire may be the least like an actual film in that there is rarely any movement ever, especially as the definition of film is that it is a “motion picture.” Also like Sleep, there are very few things throughout that show that it is even a film. Things such as a flashing light or the change from day to night are the only things that reference that time is passing. The film was also slowed down to run at sixteen frames per second, instead of the typical twenty-four. The film being eight hours also emphasizes the idea of the passing of time, as eight hours is usually the typical length of a work day. Interestingly enough, the film is of the tallest building in one of the busiest cities, if not the busiest, in the United States– a place where nobody ever witnesses the passage of time. In this way, the film can also serve as a commentary on the city itself, or life in general.

One of the other facets of Warhol’s filmography is his screen tests. Warhol made nearly 500 of these, filming the various people that came through The Factory, from close friends to various celebrities like Dennis Hopper and Edie Sedgwick. These screen tests channeled his obsession with celebrity by putting others in the spotlight and gaze of the camera. He treated those he screen tested the same way he treated those that he filmed: he gave them full control to do and say what they wanted, while he let the camera roll in a stationary position. In a way, this is one of the first instances of reality television, as those in front of the camera were given the power to dictate what happens. For some, it was an obviously embarrassing and nerve-racking experience, but for others, it made them feel like the stars they would become.

Warhol’s films, as a whole, revolve around the idea of putting the spotlight on what to most would be considered the mundane. Being able to capture these things on film is almost like making them celebrities in and of themselves. Warhol treated a building and a person sleeping in the same way that Hollywood treats explosions and fast cars. Film has the power to immortalize and capture a moment in time, and if done right, to immortalize them forever.

https://daily.jstor.org/glamour-the-gaze-and-warhols-screen-tests/

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0912238/

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/video-wonder-andy-warhols-5hour-film-of-a-man-sleeping

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/89507

http://nymag.com/nymetro/arts/art/10422/

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2001/aug/21/artsfeatures.warhol