Aurora Garrison | February 2018

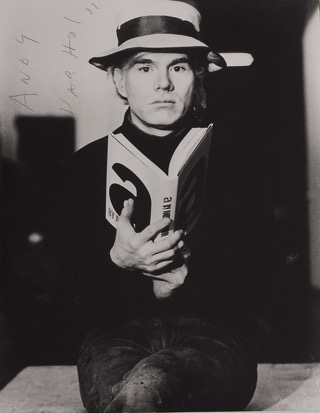

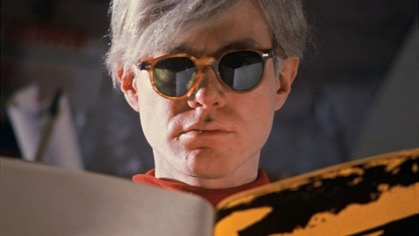

Despite rumors to the contrary, Warhol was an avid reader and his literary tastes ranged from movie star biographies to books on astronomy, plastic surgery and cookbooks. As far as Warhol was concerned, the medium of writing was worth exploring as it is mass produced to the public and widely accessible and attainable. Warhol, in addition to being well read, was an accomplished author of several books, including a novel.

Warhol’s “novel“, entitled A: a novel (1968), is over 450 pages of transcribed conversations taped in and around Warhol’s Factory in 1960s Manhattan. When it was published, the book was called “pornography” by the New York Times Book Review.

Warhol’s novel is by no means an easy read. Its jagged transcriptions document scores of amphetamine-fueled conversations weighed down by incoherent, distorted dialogue. However, after one becomes familiar with the novel and its narcotized rantings, some surprisingly poetic and haunting statements emerge from its pages, revealing Warhol the artist, author and icon – and his literary process.

Warhol muses on the beginnings of his novel in the mid-Sixties: “I think it all started because I was trying to do a book. A friend had written me a note saying that everybody we knew was writing a book, so that made me want to go out and keep up and do one too.” Warhol gives this explanation as to why he wrote A: a novel, a book on his life and the culture of the Sixties.

Warhol’s novel is essentially a stream-of-consciousness, which boils down to journal entries transcribed from 24 one-hour tapes. It is a roman à clef, meaning a novel with a hidden key, a novel about real life, concealed by a façade of fiction. The fictitious names in Warhol’s novel represent real people from his Factory days in the mid-60’s, and the hidden “key” within the story is the relationship between the nonfiction and the fiction.

Pittsburgh.

But, Warhol did not create A: a novel alone, he needed what he referred to as his “wife”. Famously, Warhol admitted “I have no memory. Every day is a new day because I don’t remember the day before.”

“That’s why I got married—to my tape recorder,” Warhol quipped, in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (1975), “Every minute is like the first minute of my life. I try to remember but I can’t.”

Unprecedentedly, Warhol records the exploits of one of his Factory pals Ondine [Robert Olivo, a Warhol superstar] for 24 hours in New York. The opus of the novel is contained in four recorded sessions: in August 1965, the first 12-hour session is made. Then, three more sessions totaling 12 additional hours are recorded in the summer of 1967, with the final session completed in May 1967.

Warhol effectively kidnaps the literary form of a novel and transforms it into a living record, his living record. The artist had his revolutionary literary approach dialed in: “So I bought a tape recorder and I taped the most interesting person I knew at the time, Ondine, for a whole day,” Warhol recalls in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol.

What follows in A: a novel is just now being re-read and researched as the popularity of Warhol soars and artists and philosophers seek the holy grail of Warhol’s essence as an artist, peeling away the enigma of the icon and the man. A: a novel is a good touchstone to the mad-capped genius of Warhol.

Written from an insider’s perspective, A: a novel can be confusing and frustratingly obscure if the reader is not acquainted with the nicknames, the icons, and the goings-on that populated The Factory. For example, the novel’s character “Drella” is Warhol himself. He is nicknamed by Lou Reed as “Drella” because Reed felt the name fit both sides of Warhol’s persona, equaling a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde combination of the two sides of Andy Warhol: Cinderella and Dracula.

In addition to his novel, Warhol also left an equally amazing legacy of his thoughts, fears, art and life in his book, The Andy Warhol Diaries (1989).

The Andy Warhol Diaries record his life over a 12-year span from November 24, 1976 to February 17, 1987, just 5 days before his death on February 22, 1987, 28 years ago.

The Diaries capture Warhol’s uncensored views on life and art, recording some of his most quotable remarks: “Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art…making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art,” and “Before I was shot, I always thought that I was more half-there than all-there – I always suspected that I was watching TV instead of living life,” Andy Warhol, The Andy Warhol Diaries.

In addition to The Diaries, Warhol wrote his book on philosophy, a cultural history on the Sixties, entitled The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) (1975). The Philosophy of Andy Warhol is loaded with his personal insights – each chapter lists a topic, such as Fame, Time or Money, under which he has numerous musings and reflections. Apart from the chapters’ subjects, the book is mostly an unstructured, stream of thought, not unlike his novel.

There is a flatness and absurdity in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol. For the most part Warhol conceals himself, but then something of his inner psyche is revealed. For example, he says he does not want to be wasteful yet wants to produce a million copies of the same image. As the artist unveils a perverse contradiction between quantity and waste, a major theme in his art is brought to light. The major theme of systematic repetition, when a hyper-resonant motif, for a widely known object, like the dollar sign for money, already interpreted through the media is printed by the masses and called art, it loses its value and becomes a copy of itself.

Andy Warhol has cheated death once in 1968 after surviving a violent attack and gunshot wounds; yet he survived then, as he survives now. Decades after his death, Warhol lives on through his artistic and literary legacies. And what survives is the mysticism of Warhol the man, Warhol the artist and Warhol the writer.

Powerfully and insightfully, Warhol recognizes – with the eye and mind of an artist – the importance of his portraits and colorful depictions of soup cans and household cleaning products that captured the commercial era of the 60s and the emerging Pop Art movement.

In his own words: “People need to be made more aware of the need to work at learning how to live because life is so quick and sometimes it goes away too quickly.” It was ultimately Warhol’s artistic vision that led him to see the world anew, taking images from our everyday life and elevating them to art.