By: Taylor Moran

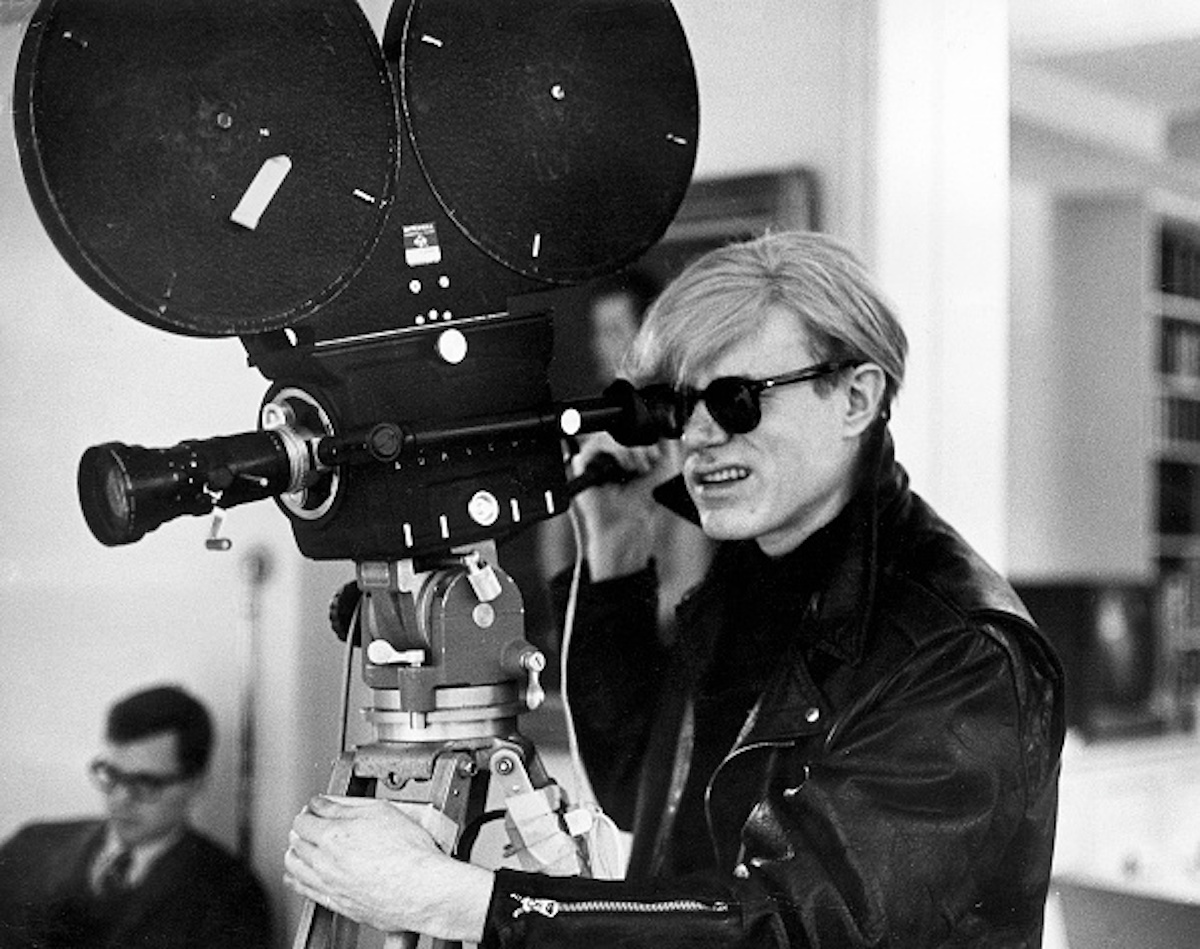

Have you ever had the voyeuristic desire to be a fly on the wall? Watching a Warhol film might get you there. From 1963 to 1968 alone, Andy Warhol created over 600 experimental films tailored to his role as a social observer. Always in search of his next muse, he spent his life in a state of fascination; it was only a matter of time before he turned to film as an extension of his art. From Kiss to Empire to Tub Girls the camera acts as the fly, usually set in one spot and left alone to see what happens next. Sometimes dubbed “anti-films”, they were known for their refusal to heed to any prescribed idea of what a movie is supposed to be.

In the world of narrative cinema that we are so accustomed to, drama unfolds constantly. Time not used to drive a story forward is typically viewed as time wasted. With so much happening onscreen, it is easy for us to forget ourselves. We temporarily leave real life behind and suspend belief. Not so in Warhol’s films. “When nothing happens,” Warhol once said, “you have a chance to think about everything.” He wasn’t so interested in acting, or at least not in the way we are used to it. He wasn’t interested in a loss of reality either. Warhol wanted to turn the mirror back on his audience, to challenge them to sit in discomfort and let their thoughts wander.

Instead of speeding things up and moving from scene to scene, he did the opposite. Warhol would often drag out one shot for as long as possible or repeat the same footage multiple times. In many of his movies, Warhol filmed at 24 frames per second and projected it at 16, thus giving it a slower effect. Imperfections were often kept in, conventions ignored. However, it can’t be denied that when the camera was on Warhol’s superstars were aware of its presence. His films were not so much a presentation of total reality, but an immersive experience that made his audience much more aware of it. He turned reality into an art form, the banal into the beatific, simply by letting the true nature of his stars shine through.

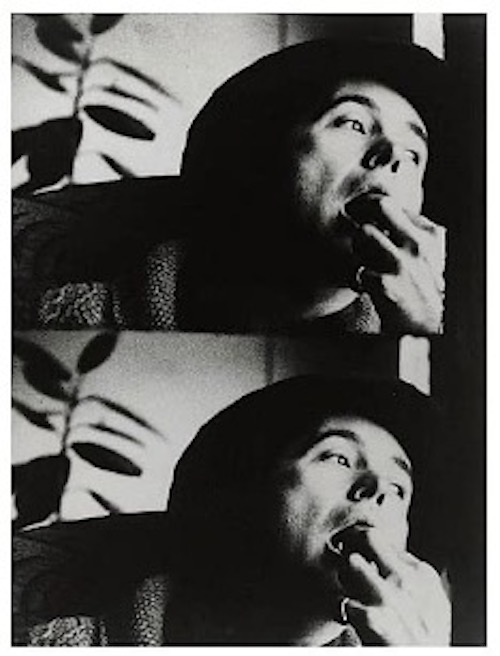

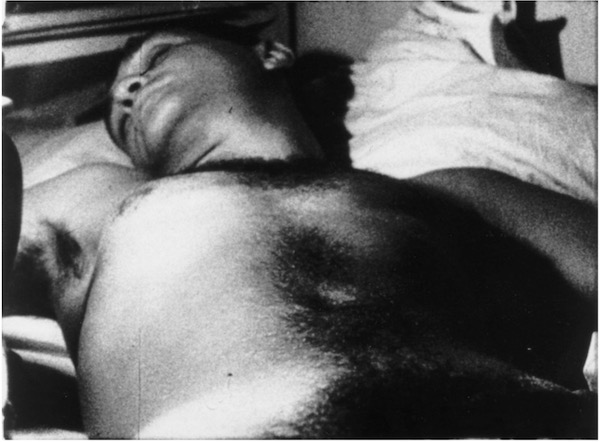

In May of 1963, Warhol bought a 16mm Bolex camera and asked his lover John Giorno if he wanted to be a movie star. “Of course,” Giorno replied. “I want to be just like Marilyn Monroe.” The experiment—which later became Warhol’s first film, Sleep—would set the conceptual tone for his future films. During five hours of looped footage the camera studies Giorno dozing from several different angles, just as Warhol sometimes did when he watched him sleep at night (Giorno claimed that during this period Warhol took speed and couldn’t sleep himself). Like with Blowjob and Eat, we observe one subject for a certain length of time doing one simple thing. There is almost something scientific about it, as if through film Warhol aimed to create a living study of his subjects.

It’s likely he wanted to accomplish just that. In The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again),Warhol has a conversation about film with someone named “B”:

“B: I wanted to make a film that showed how sad and lyrical it is for these two old ladies to be living in those rooms full of newspapers and cats.

A: You shouldn’t make it sad. You should just say, ‘This is how people today are doing things.’”

In Sleep, Warhol laid bare his fascination with human mechanisms. Despite how detached and clinical it might seem, there is a naked tenderness at the heart of his films. He liked watching people be people and for him, that was enough.

Warhol shot Poor Little Rich Girl with Edie Sedgwick two years later in 1965. Having been a Shirley Temple fan as a kid, he took the title from one of her movies. In the 1936 original, a young girl is sent to boarding school by her father but ends up running away with a troupe of vaudeville performers. The parallel between Temple’s character and Sedgwick’s life must have been kismet to Warhol. After being sent to a boarding school (and later a psychiatric institution) by her authoritative father, Edie moved to New York City with trust fund money she received from her grandmother. There she met Warhol and joined his “troupe” at the Factory. It was a quick love affair: Poor Little Rich Girl was filmed only one year after their meeting. Separating Sedgwick’s life from her onscreen performance wasn’t something Warhol wanted to do, however—she was already a character in her own right. For him, the real thing was more interesting.

After the film was developed, Warhol realized the footage was totally out of focus. Rather than toss it, he decided to keep the first half-hour as is and reshoot the rest. In that first 30 minutes a hazy Edie Sedgwick wakes up and wanders around the room smoking cigarettes, putting on makeup and doing leg exercises. She talks on the phone, orders orange juice and coffee. The Very Best of the Everly Brothers plays in the background. While sitting at her vanity getting ready, she sings along to “Crying in the Rain”: Only heartaches remain, I’ll do my crying in the rain…The simplicity of the moment allows its intimacy to show through. Even if Edie is a poor little rich girl, her experience—its loneliness, its endearing sameness—is universal.

When she comes into focus later on, Edie talks to a man in the room who has just woken up. He remains off-camera throughout, which keeps our focus on Edie’s face. They have a conversation about dreams and she shares one she has about walking down a set of never-ending marble stairs. These meandering discussions show why Warhol was so enamored with Sedgwick: on film everything she says and does rings true. There is an animated liveliness about her, a spontaneity that Warhol must have adored. Whereas most directors in show biz love a professional who can deliver, he favored amateur performers like her because they never did the same thing twice. And there was nothing phony about them.

All of Warhol’s earlier work rose to its crescendo with Chelsea Girls, which he shot in 1966 with Paul Morrissey. It was the first of Warhol’s films to gain mainstream recognition; in December of that year it was screened at the Cinema Rendezvous, an uptown New York theater that normally showed family movies. One year later it was banned in Boston for obscenity. This only excited Andy since it meant the film would garner more attention.

Like his other films, there was no narrative and no sense that the characters were there to put on an act. Only this time instead of focusing on 1-2 subjects, he used a split screen to showcase several inhabitants of the Chelsea Hotel interacting simultaneously. While Pope Ondine and Ingrid Superstar talk aimlessly (“Crying is really something you should do regularly…what can I say to make you cry, Ingrid?”), Nico plays with her son Ari and cuts her bangs. Brigid Berlin prepares a needle. In one room a group of girls, including Hannah Hanoi and International Velvet, huddle around arguing back and forth. Patrick Fleming and Ed Hood laze around in bed smoking cigarettes. In the last hour of the film the whole cast is lit in vivid, flashing colors on one side of the screen while Eric Emerson spiels in a mesmerizing voice on the other (“I wish I was a drop of sweat being licked by someone…and then taken into their body”)

Over the course of three hours we get the sense that we’re watching two enclosures in a menagerie. The actors are free to roam and do as they please, but there is something cage-like about the frame. It harkens back to Warhol’s screen tests when actors were forced to sit in one spot and confront the camera. Here, they are ushered together and forced to confront each other. Ultimately the inhabitants of the Chelsea are left to their own devices to entertain themselves. So they do what people do: eat, talk and try to get to know one another. Warhol wanted to capture that, the real things that happened when people got together.

“What I was actually trying to do in my early movies,” Warhol explained, “was show how people can meet other people and what they can do and what they can say to each other. That was the whole idea: two people getting acquainted. And then when you saw it and you saw the sheer simplicity of it, you learned what it was all about. Those movies showed you how some people act and react with other people. They were like actual sociological ‘for instance’s’. They were like documentaries…”

Chelsea Girls was perhaps Warhol’s greatest “sociological for instance”. It was like a documentary because Warhol’s actors were able to be themselves on screen, in their natural habitat. It was not actually a documentary; while Warhol did film scenes at the Chelsea Hotel and a few of the stars lived there, much of the film was shot at the Factory and various apartments across the city. However, the intention was to make something real. “The idea was they were all characters that were around and could have been staying in the same hotel,” Warhol said. Even within the few fictional elements of his films, Warhol aimed for authenticity—not so much for purist reasons, but because that was what interested him. He presented reality the way he saw it. So when we see the way Warhol looked at the world in his 1960’s films, we see the oft-overlooked beauty of real life—the hours spent passing time together in boredom, doing things that people do.