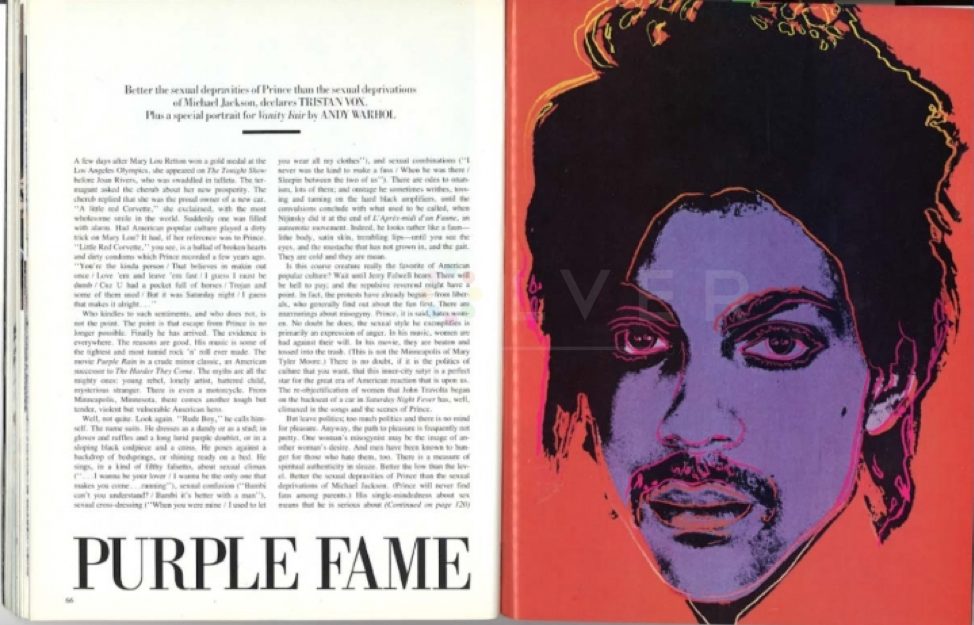

Andy Warhol is venerated for his pop art, particularly his vibrant depictions of iconic celebrities. However, his reproduction of other photographers’ images has always been a topic of great contest for the artist. Though Warhol died over thirty years ago, the Andy Warhol Foundation continues to battle for image rights. In 2017, the Andy Warhol Foundation launched a preemptive lawsuit against photographer Lynn Goldsmith, who captured photos of the late musician Prince in 1981 for Newsweek. Though Goldsmith’s photographs were never published, Andy Warhol was commissioned by Vanity Fair in 1984 to produce a pop art recreation of one of the images, after licensing it for $400. Warhol continued to use the image for his portfolio of Prince paintings, taking his own spin on the vulnerable black and white photo of the artist. Though Warhol’s reproductions became an iconic part of his portfolio, Goldsmith alleges that she had not known about Warhol’s reproduction of her photograph until it was published in a 2016 Vanity Fair article following Prince’s death.

Though Goldsmith did not initially intend to seek legal action, she filed a countersuit after the peremptory challenge from the foundation, stating: “I know that some people think that I started this, and I’m trying to make money. That’s ridiculous––the Warhol Foundation sued me first for my own copyrighted photograph.” However, rather than having a standard trial, the parties requested a summary judgement, in which the judge makes a unilateral ruling on a case based on statements from the defense and prosecution.

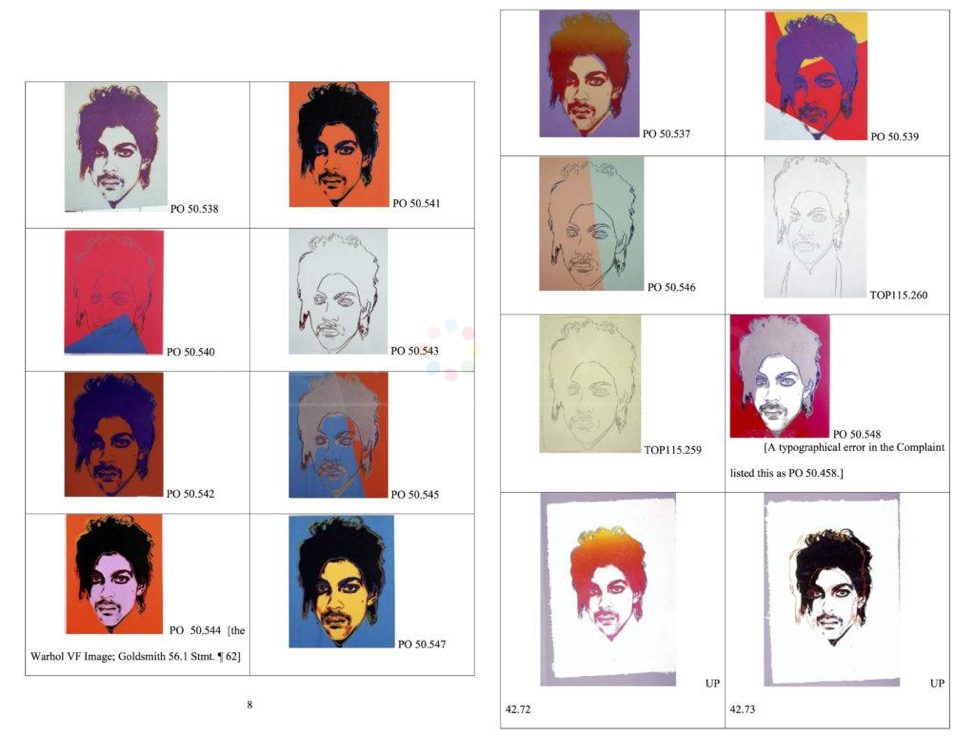

John G. Koetl, the presiding New York State District Judge for the case, ruled in favor of the Andy Warhol Foundation. Koetl argued that though Warhol used Goldsmith’s photograph as a reference image, he “removed nearly all the photograph’s protectible [sic] elements.” Thus, Warhol did not violate the photograph’s copyright. Koetl explained his judgement through the perceived transformation of the image from Goldsmith to Warhol: “The Prince Series works can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure….The humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith’s photograph is gone. Moreover, each Prince series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince — in the same way that Warhol’s famous representations of Marilyn Monroe and Mao are recognizable as ‘Warhols,’ not as realistic photographs of those persons.”

Judge Koetl’s ruling also reflects Vanity Fair’s lawful use of the image. Goldsmith recalls the magazine requesting to license the photo “for an artist to reference to create an illustration,” for which they provided both payment and photo credit. However, Goldsmith still believes that Andy Warhol himself violated her copyright by continuing reproductions through his Prince portfolio.

Warhol was known to use popular images for the sources of his paintings, for which he found himself in several settlement deals out of court. Such settlements included the image for his Flowers series, which was taken from Patricia Caufield; his Jacqueline Kennedy images, originally from Fred Ward; and Warhol’s Birmingham Race Riot, which was sourced from Civil Rights photographer Charles Moore. After the recurring disputes, Warhol vowed to start using his own photographs to use for the basis of his works, such as those he took of Mick Jagger and Muhammad Ali. However, Warhol made an exception to the new rule after Vanity Fair’s license of Goldsmith’s photo.

Despite the judge ruling in favor of the foundation, Goldsmith stated that she plans to pursue an appeal, which will be submitted to an appellate court for definitive ruling. Goldsmith’s lawyer commented on the results of the case in an email. “Obviously we and our client are disappointed with the fair use finding, which continues the gradual erosion of photographers’ rights in favor of famous artists who affix their names to what would otherwise be a derivative work of the photographer and claim fair use by making cosmetic changes,” Lawyer Barry Werbin writes, hoping that an appeal “will be successful and pull in the reigns of transformative use where photography is concerned.”