By Mason Rogers

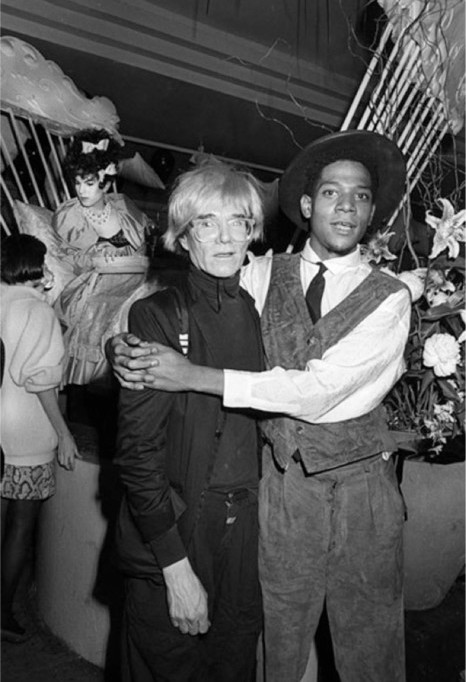

By the early 1980’s, Andy Warhol was already one of the biggest figures in the art world. The success of his vibrant factory-style paintings had endowed him with the recognition of giants, and with an international name that conjured a unique tradition of artwork. Jean-Michel Basquiat, however, had just made his breakthrough into the public eye. After years spent as a fairly isolated graffiti artist, he was hungry for validation and stood as a neophyte entering a cultural landscape that was the antipode of his upbringing in 1960s Brooklyn. Selling t-shirts and postcards on busy city streets, he had not yet received the recognition that would catapult his name towards the echelon of prestige where Warhol resided. Neither one predicted that their future friendship would snowball into one of the most admired couplings postmodern art has ever seen.

Jean-Michel becomes Basquiat

In the summer of 1978, Jean-Michel Basquiat left his family home in Brooklyn and headed for Lower Manhattan. At the time, the area erupted with creatives, and quickly became romanticized as the promised land for all artistic expression. Illustrators, poets, film makers, and all artists alike took pilgrimage to the scene in search of a dazzling backdrop to varnish their careers and gift themselves with starry-eyed inspiration and bountiful connections.

When Basquiat arrived, he was seventeen years old and poor. He recalls his lifestyle in an interview with Tamra Davis from 1985: “I used to look for money at the Mudd Club on the floor… Walking around for days and days without sleeping.” Under the alias “SAMO,” he vandalized buildings with provocative epigrams throughout Manhattan. The work often incited contemplation or surprise. It mainly invoked a vague awareness of the bleak reality and structural violence faced by black working-class America, while encouraging an avant-garde approach to life in general and a critical attitude towards society at large. His willpower and dedication to his art paid off, as he caught public attention with his graffiti and gradually penetrated the SoHo art scene.

Basquiat quickly gained recognition amongst local SoHo magazines and nightclubs. His solo career took off in 1980, when he began participating in gallery shows and his paintings were admired by fellow artists and critics alike. In 1981, he sold his first painting to Debbie Harry, lead vocalist for the punk-rock act Blondie, for $200.

Still, Basquiat’s career and personality were waiting patiently at the launchpad. Meanwhile, Andy Warhol was saturated with opulence, receiving commissions from prestigious socialites and celebrities from all venues of the entertainment industry. It wasn’t until 1982 that the two artists met and sparked a friendship that would ignite unmatched talent at both ends, forming an astoundingly unique synthesis of rags, riches, and postmodern art power.

Warhol Meets the Radiant Child

When their relationship began, Andy regarded Basquiat with nonchalance, and perceived him as little more than a hopeful kid who tried hard to make a name for himself in the New York art scene. However, if we study their relationship more closely, we see that the pop-art master held quiet notes of admiration for the grunge-laden 21-year-old from the moment they met.

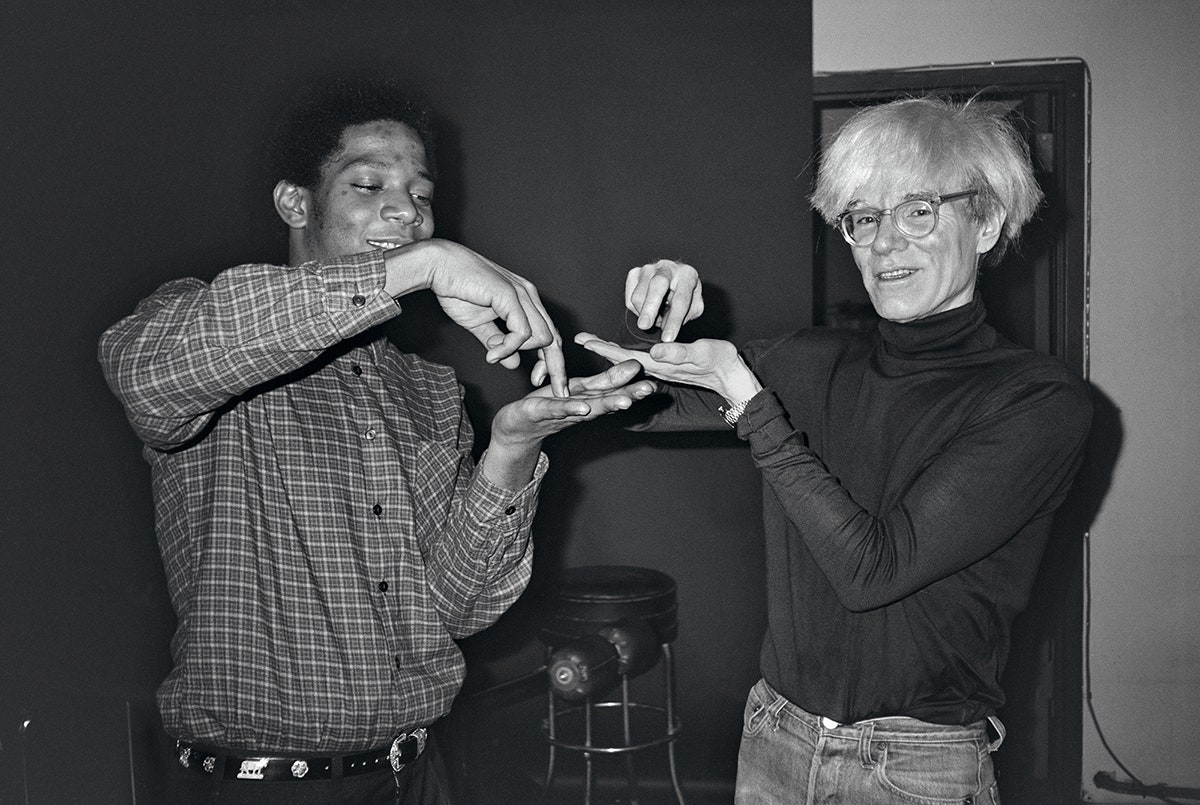

Though many believe Basquiat first met Andy when he encountered him at a restaurant and attempted to sell him postcards—as attested to in Julian Schnabel’s 1996 biopic Basquiat—the gallerist and collector Bruno Bischofberger claims to have formally introduced them to each other when he invited them to lunch in late 1982.

Revolver Gallery owner Ron Rivlin had the privilege of speaking with Bruno Bischofberger about his experience with collaborations between artists he represented, and his memories detail the convergence of Warhol’s and Basquiat’s lives. During the expansion of the post-modern art movement, Bischofberger became interested in the idea of collaborations for various reasons; one of them being the paintings that visiting artists would create in tandem with his 3-year old daughter at his home in Switzerland. The young Basquiat, being one of those artists, seemed a perfect fit for collaborative projects, especially when he expressed to Bischofberger that what he found most influential was the work of 3-to-4 year-old children.

As Andy’s main dealer since 1968, Bischofberger had agreements with him involving collaborations with fellow artists: mainly proposals to invite them to the Factory and for material which he saw interesting for Interview Magazine. He trusted Bischofberger’s discretion, and let him bring new creatives to the Factory where portraits were taken and the two artists would trade works, even though Andy was aware that his pieces would be worth significantly more. But when Bischofberger mentioned his interest in Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy was surprised, asking him “do you really think that Basquiat is such an important artist?” According to Bischofberger, Andy’s initial skepticism towards Basquiat’s character was glaring: “Warhol was not familiar with Basquiat’s new work and told me that he remembered having met the artist on one or two occasions, on both of which Warhol had felt him to be too forward.” Basquiat, however, was resolutely eager to work with Warhol in any capacity, and Andy reluctantly allowed Basquiat’s company at the Factory. Andy’s first mention of him in his diaries comes from that meeting, in an entry dated October 4th, 1982:

“Down to meet Bruno Bischofberger (cab $7.50). He brought Jean Michel Basquiat with him. He’s the kid who used the name “Samo” when he used to sit on the sidewalk in Greenwich Village and paint T-shirts, and I’d give him $10 here and there and send him up to Serendipity to try to sell the T-shirts there. He was just one of those kids who drove me crazy.

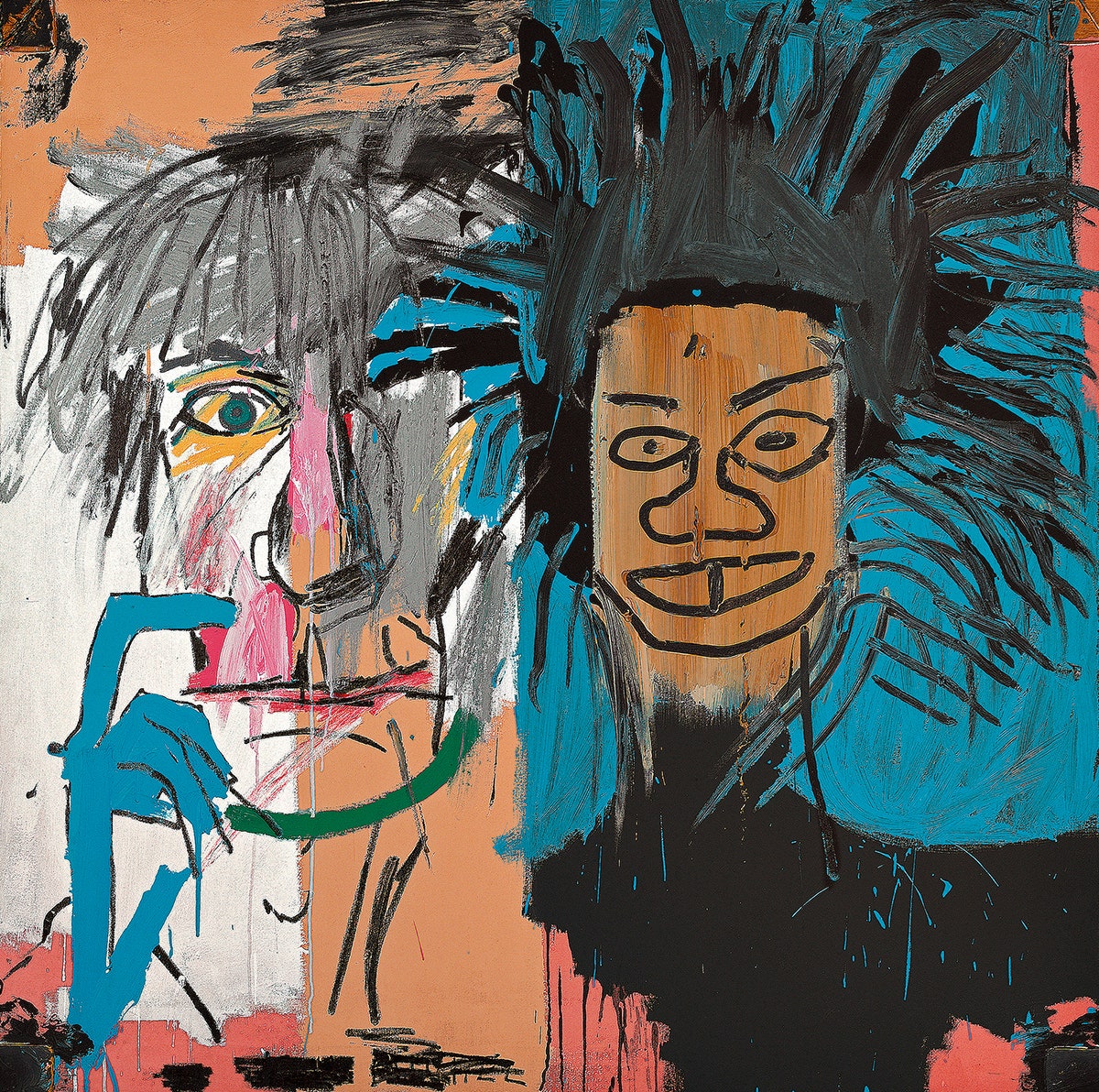

Andy took the customary portraits on his Polaroid, and Basquiat asked if Bischofberger would photograph the two artists together. Once it was done, Basquiat rushed out, declining Bischofberger’s plea for him to stick around for lunch. Less than two hours later, Basquiat’s assistant showed up to the lunch buffet with a large painting of the two artists together in his typical primitive style. The encounter that day turned out to be the perfect chance for the younger artist to make an impression on the elder. Bischofberger remarks on the scene: “He just went home and after this little polaroid of Andy and him, he painted this painting very fast, a really great masterpiece.” The event is also recollected in Andy’s diary where he writes, “he went home and within two hours a painting was back, still wet, of him and me together… He told me his assistant painted it.” And as Bischofberger recalls: “Oh, I’m so jealous!” Andy exclaims, “He’s faster than me!”

From that day onward, Andy’s diary is littered with mentions of the young artist: his girlfriends, the state of his apartment, the couple working out together, photo shoots, Andy’s opinions of his habits, and playful compliments: calling him “cute” and “adorable.” He was hooked, and the symbiotic relationship between the two gave an edge to both artists’ creative and social lives. For Andy, Basquiat was a source of the innovation and unprocessed artistic energy that he needed to inspire the future of his career. And things couldn’t have been better for the bohemian rookie. Basquiat sought fame and access to a larger empire of art; Warhol’s blessing had a colossal effect on his reputation and his ego. Andy was the master of the game that Basquiat wanted so desperately to play, and his stake in Warhol’s career is owed partially to the risky exit he made on that day in 1982. As their friendship blossomed, the artists painted more portraits of each other and began collaborating intensely.

The Collaboration

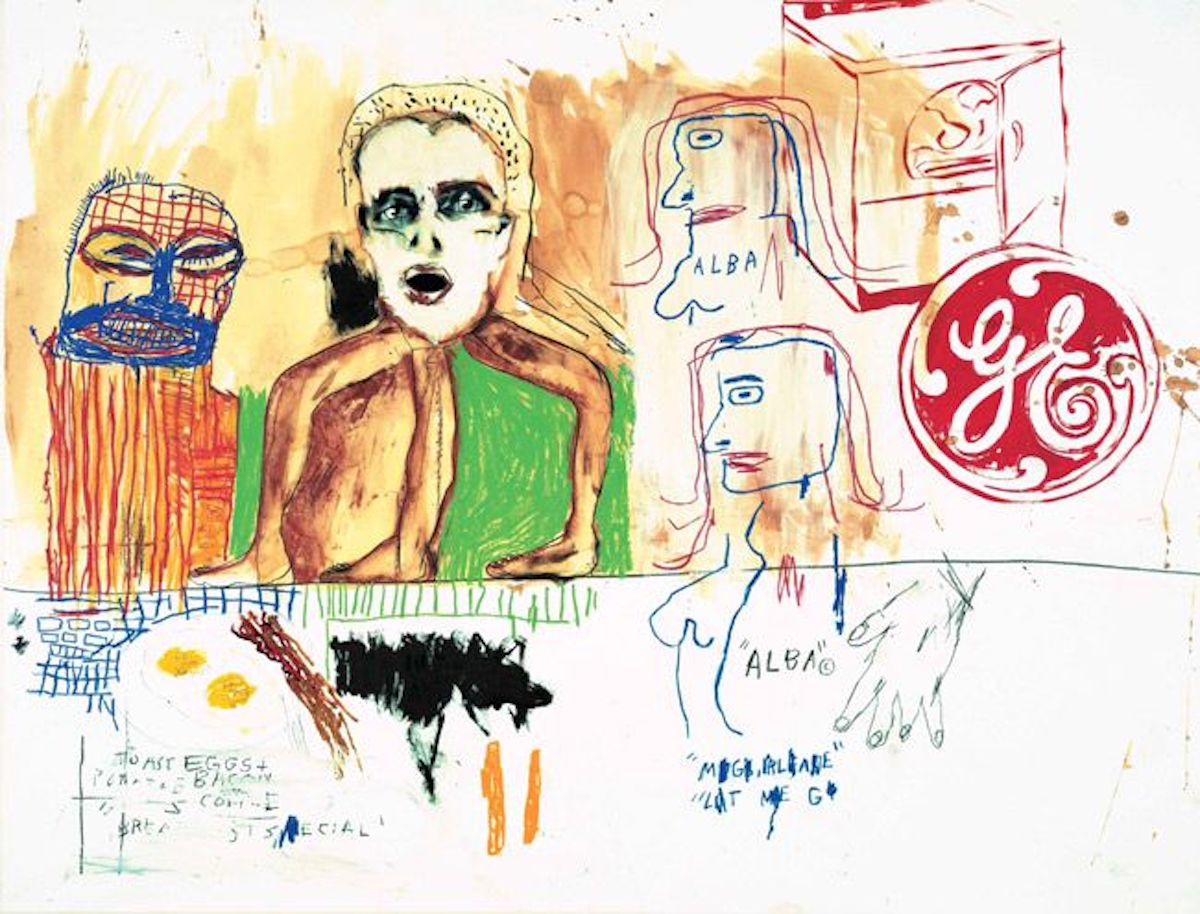

It is a little known fact that the Warhol and Basquiat collaboration paintings were not commissioned, and were initially kept a secret from Bischofberger. Originally, he expressed interest in a collaborative triad between Warhol, Basquiat, and Francesco Clemente, who both artists knew and admired. Bischofberger’s assignment was simple: each artist was to start painting individually on five separate canvases with oil or acrylic, leaving room for the “mental and physical space” of the other painters, to whom the canvas would be passed in succession. Bischofberger insisted on this method: if the artists worked independently and without communicating desires for the final product, the pieces would explode with spontaneous energy and capture the essence of each artist on a single canvas in a myriad of stylistic arrangements. Andy used his silkscreen technique on all fifteen paintings, and they were shown in Bischofberger’s Zurich gallery in an exhibition called Collaborations – Basquiat Clemente Warhol between September and October 1984. The work was a success, and a publication of the same name soon followed.

“These combined paintings of Jean Michel and me and Clemente that [Bruno] said were “just a curiosity that nobody would want to buy” that he paid $20,000 for like fifteen pictures for, he’s now selling for $40,000 or $60,000 apiece! Yes! And I have a funny feeling that he’s actually giving Clemente more because I can’t see him doing this for this little.” – September 17th, 1984

Andy Warhol, Jean-Miche Basquiat, & Francesco Clemente, Alba’s Breakfast, 1984

Six months after the show, in the Spring of 1985, Bischofberger made one of his routine trips to New York to see Andy. It was then that Andy revealed to him that he and Basquiat had been working privately together on a large collection of paintings: “He seemed a bit embarrassed, presumably because he and Basquiat had not mentioned it earlier to me.” One entry in Andy’s diary admits this, when he writes that, while at his office, “Bruno was there and Jean Michel was hiding our work from Bruno—the ones that just Jean-Michel and I are doing. [He] doesn’t know about these that’re just the two of us.” This entry, being from the Spring of 1984, reveals that the duo excluded Clemente and started a separate project an entire year before ever telling Bischofberger. Andy and Basquiat felt that Bischofberger didn’t have any say in the paintings themselves, but as their representative, he would be entrusted with them. He was both shocked and enthused by the secret paintings and purchased numerous large-scale works from them, planning to exhibit them the following year.

In these secretive paintings, we witness not only the genius of each artist in cohabitation, but the influence and direction both artists delivered to one another throughout their relationship. The beneficial effect both artists had on one another is evident: Basquiat was interested in Warhol’s clout, and Warhol sought young blood to stimulate his expanding oeuvre. Beyond this, the two were intimate companions, using each other as an outlet to express grievances about the demands of the art life while exchanging techniques and habits during day-to-day painting sessions in the Factory.

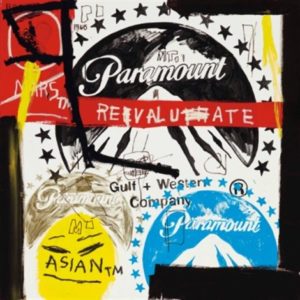

Bischofberger describes Andy’s contribution to the pieces as “a kind of poster style featuring heraldically hand painted enlargements of advertising images, headlines and company logos but partly in painterly free brushstrokes, similar to a part of his early works of 1961 and early 1962.” Basquiat had previously mentioned to Bischofberger that he thought Andy was “a fantastic painter,” and that he was going to try to convince him to start painting by hand again. It seems to have worked for Andy, who writes in a diary entry dated September 1984 that Basquiat got him “into painting differently, so that’s a good thing.” Basquiat took technical inspiration from Andy as well and used silk screening on several of the collaboration pieces, which Andy would then paint over.

The pieces ultimately represent a free-spirited and improvised approach to the idea of cooperation. Each artists’ work was simultaneously obliterated and adorned by the other: marking images out, painting over one’s contributions, supplementing the other’s work with icons and rugged text, and therefore articulating their idiosyncrasies between and on top of each other. For each artist, it was a fruitful exercise, as both Warhol and Basquiat cherished the solace found in one another’s company.

The Downfall

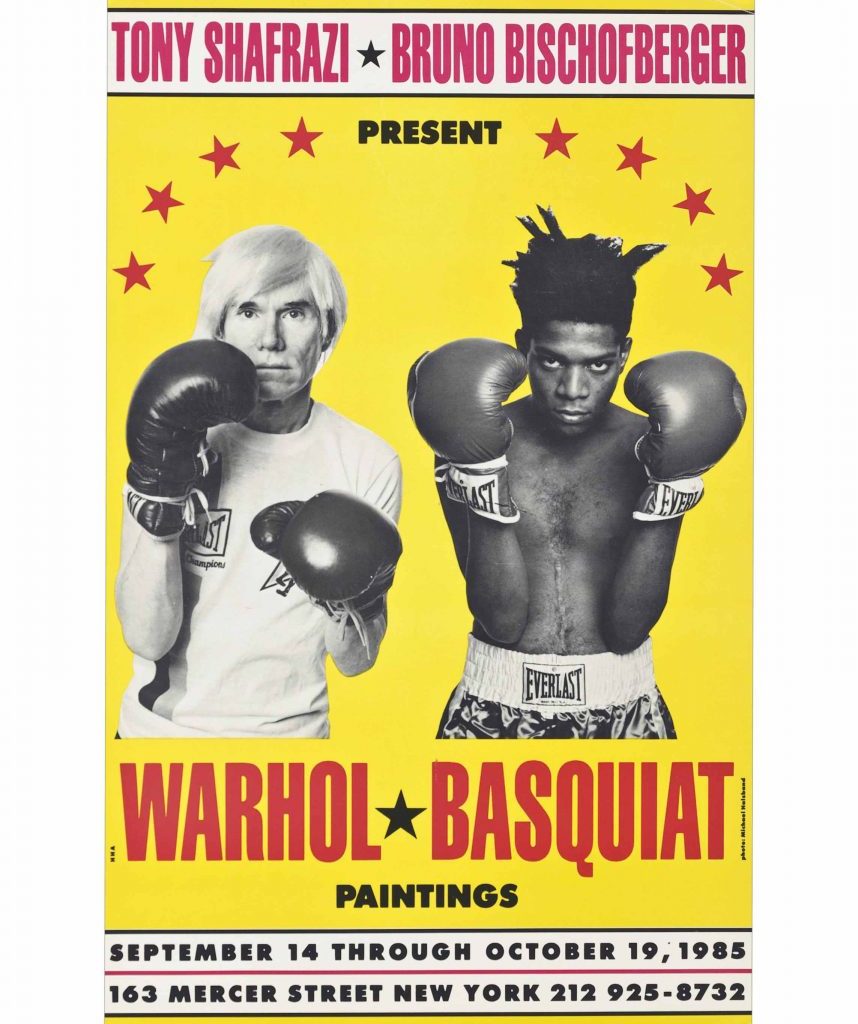

In September 1985, sixteen of the Warhol-Basquiat pieces were shown at the Tony Shafrazi gallery in Lower Manhattan. The creation of these paintings was a passionate and enlightening venture for both artists, but their exhibition, titled “Paintings,” was a complete misfire. Not only did the press vehemently criticize their work, but critics also took fateful jabs at the very meaning of their relationship. According to Bischofberger, art critic Vivien Ranor described the work in The New York Times as “Warhol’s manipulations,” and claimed he was using Basquiat as a “mascot.”

While a bit of bad press and disinterest was nothing new for Warhol, Basquiat was undoubtedly counting on their show to reinforce his selfhood as an artist and mobilize his position in the high art scene. In Andy’s diary, he apologizes to Jean-Michel about the “mascot” remark, and supposedly, he was not mad about it. But the failed exhibition certainly dismantled Basquiat’s ego, and he no longer visited Andy for their regular painting sessions at the Factory. A few months later, Andy writes in his diary: “Jean-Michel hasn’t called me in a month. So I guess it’s really over.” Ultimately, the two never broke up for good and kept in touch through phone calls and occasional visits. Two years later, Andy’s death had a jarring impact on Basquiat’s already unstable emotional wealthfare. He continued to receive critical acclaim and went on to travel the world as one of the few internationally celebrated black artists of his time. Less than two years after Andy’s passing, on August 12, 1988, a heroin overdose ended Basquiat’s life.

The assertion of Basquiat as Andy’s mascot probably relates to the public’s perception of Andy and prior criticisms labeling him as a “business artist,” as well as the apparent decline in his career in the late 1970s. The press likely saw his relationship with Basquiat as a flagrant attempt to co-opt another young artist for the sake of remaining relevant. Still, the breakup was upsetting for Andy, partially because it is likely that he had plans to expand upon their collaborative work. After Andy’s death in 1987, unfinished paintings were sometimes shown by his Estate, some of which Bischofberger believes to be the lonely beginnings of intended collaborations with Basquiat.

The State of the Art Today

Today, it is difficult to imagine how the market value of a Warhol-Basquiat collaboration could have ever been so trivial. As the history of art progresses and the passing of time affords us new insights into the artifacts of the past, cultural material will always become inhabited by new layers of meaning. Regardless of whether we are realizing the faults of our past judgement or simply re-analyzing the phenomena of days long gone, our search for meaning often ends in humble gratitude for the great legacies and works of those before us. This is especially true for the relationship and work of Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Although their collaborations had initially failed, their works now attract global attention and acclaim: their 1984 painting Olympics sold for more than $10 million in 2012.

When we compare the two artists conceptually—Warhol’s project of reproducing the spectacles of celebrity life and quotidian consumption, alongside Basquiat’s neo-expressionist sensibility, originating as an intention to document the cultural scene of the Lower East Side in the 1970s and juxtapose that culture against the unbridled wealth of the bourgeoisie—the two seem like an unlikely duo. The magic of the Warhol and Basquiat collaboration is not found in the cross-pollination of their styles, but emerges from the separate idiosyncrasies of their works, manifested intimately on the landscape of the canvas. What unites the two is perhaps their willingness to imbue the mundane and the symbolism of working-class life with the glamour, prestige, and wealth of 20th century America that they held as sacrosanct. Warhol, with his desire to communicate the perfection and convenience that were manifest in commercial items like Campbell’s Soup cans or Coke, and Basquiat with his mission of expressing his interior life and revealing the paralyzing dichotomies that continue to rule the world today: binaries such as poverty and wealth, and the structural racism of America pitting minorities against a white ruling class. In different ways they were deeply attuned to similar spheres of life, and each one saw what the other’s work neglected. Where Andy saw humble perfection, Basquiat saw the horror that shadowed it.

Warhol and Basquiat did not bring about a synthesis of style culminating in a single great body of work. Rather, their work represents the miraculous collision of two cultural champions who forged massively separate traditions, and unfolds in a revelation of art history’s winding trajectory through time and space.