For Andy Warhol, the boundary between art and self was intriguingly blurred. His artistic expression extended beyond the canvas, manifesting intimately in his most personal medium, which was neither silkscreened nor brushed with saturated colors. Rather, it lay closer to the skin—a series of ever-evolving wigs, transitioning from blonde to silver—becoming integral to his enigmatic persona.

Initially borne out of dissatisfaction with his looks, Warhol compensated for the premature balding that ran in his family by concealing it, but over time his hairpieces became a vital tool in his workshop of ceaseless self-reinvention. Much like his art, they were both a mask and a statement; a protective layer and a medium of expression. Warhol, the artist, author, filmmaker, producer and publisher, epitomized his multifaceted identity through his series of wigs. As artifacts, they offer us a tangible connection to the artist who famously declared his love for the superficial, yet whose art consistently delved into the depths of mass cultural mythology and reflected upon commodified images.

The collection at Revolver Gallery now includes a significant piece of this narrative: Warhol’s “Death Wig,” — the last he wore. This wig, emblematic of Warhol’s final years, weaves a story of fame, identity, and an artist’s contemplation of mortality. It was one of his most glamorous and meticulously styled hairpieces, offering a rare glimpse into the man behind the iconic persona, delicately balancing his public image with his private truth.

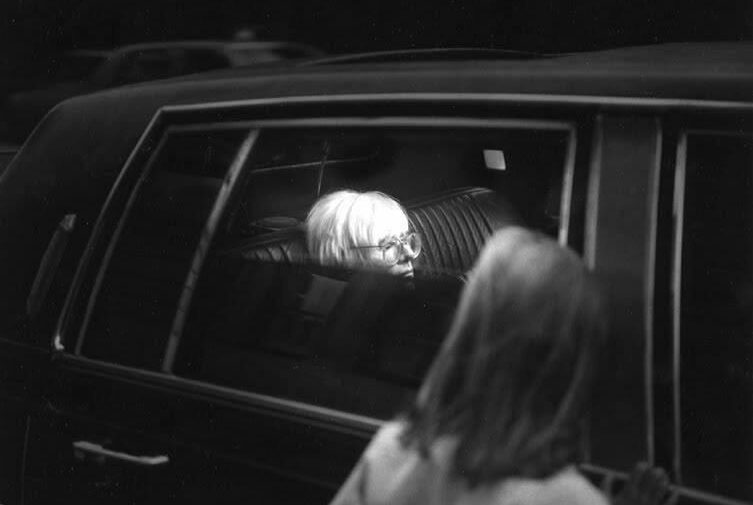

As an artist and celebrity who meticulously managed his image, Warhol’s use of wigs was a masterful play on image and perception. His choice of wig colors—initially a tawny brown, then blonde, later incorporating white, gray, and silver, with darker hair at the back—mirrored his exploration of identity through his art; the interplay between the seen and unseen, the real and the enhanced.

From the vibrant atmosphere of the Silver Factory to his reflective later years, Warhol’s wigs were as much a part of his public image as they were a symbol of his personal struggles, intertwining with themes of celebrity, authenticity, and the human condition. Join us as we unravel the silver strands of Warhol’s self-crafted image by delving into the dynamic interplay between Warhol’s changing use of wigs and his artistic journey.

Before and After: Warhol’s Hair Loss and Ideal Self-Image

In his early twenties, Andy Warhol confronted a personal challenge that would manifest poignantly in his art: the onset of thinning and graying hair. This physical transformation not only impacted Warhol’s self-image but also influenced his artistic direction.

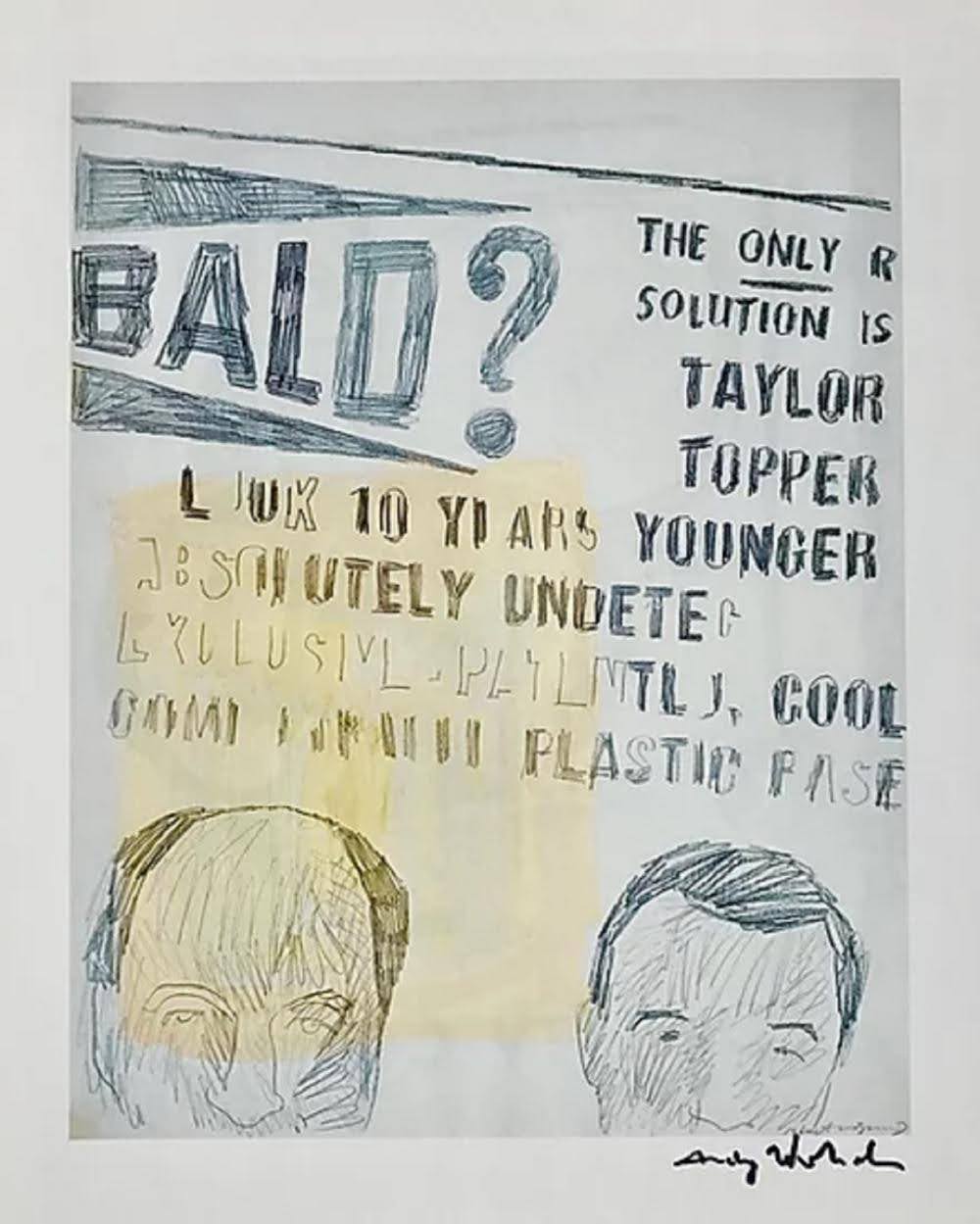

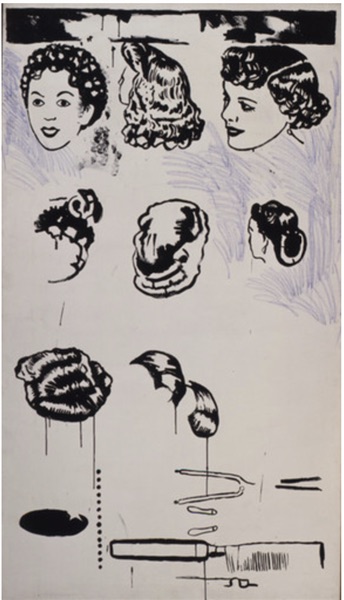

Bradford Collins’ analysis in a 2001 issue of American Art identifies Warhol’s early black and white works as a reflection of his struggles with self-image. Drawing inspiration from classified ads, Warhol created Pop Art drawings and paintings like Wigs (1961) and Bald? (1960) that directly addressed these concerns. In these works, Warhol delved into his vulnerabilities, using hair and hairpieces as symbols to explore societal anxieties surrounding his personal image. These pieces not only reflected Warhol’s search for remedies to his thinning hair but also marked the beginning of his journey in using personal experiences as a lens to examine broader cultural themes.

Bald? captures the anxiety surrounding hair loss with a stark, advertisement-like layout. Its use of text and image—commercial in style—addresses a concern that was intimately familiar to Warhol. At the bottom, two sketched heads are depicted, one with a visible scalp suggesting baldness, and the other with hair, perhaps illustrating the “before and after” effects of the product. The sketch style is loose and unrefined, giving an intimate, hand-drawn quality that contrasts with the commercial nature of the text. This artwork aligns with Warhol’s personal experience of hair loss, mirroring the insecurity and search for solutions that often accompany such changes.

The piece is confrontational in its questioning, with “BALD?” written boldly at the top, while the offered solution, “TAYLOR TOPPER,” suggests a commercial remedy that Warhol himself might have sought. Indeed, a distributor of Taylor Topper hairpieces was located in New York City, not too far from Paul Bochicchio’s wig workshop.

Wigs, with its repetitive imagery of idealized female beauty and disembodied hairpieces, comments on the facade of appearances. The variety of hairstyles represented in the artwork not only reflects the commercial aspect of beauty but also resonates with Warhol’s own use of wigs as a transformative tool. The plurality of the “wigs” featured in this artwork unsuspectingly foreshadow the plurality of wigs and wig styles that Warhol would use as a public figure. Perhaps a nod to the gay community, feminine wigs were also the essential accessory for drag queens to affect their transformation. By adopting wigs in his personal life, Warhol could manipulate his own image, an act that echoes through the serial repetition and variations of wigs in this artwork, emphasizing the notion of hair as both a personal and commercial accessory.

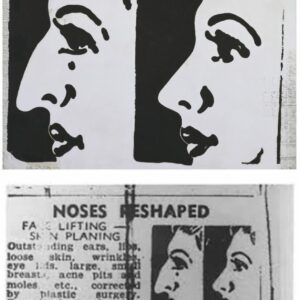

Bottom: The National Enquirer, circa 1960.

Before and After was part of Warhol’s first showing of Pop Art paintings, which served as the backdrop for New York department store Bonwit Teller’s window display in April 1961. The source that Warhol drew from was a recurring National Enquirer ad, showing two profile silhouettes. The artwork alludes to the cosmetic changes that Warhol underwent in his own life, such as the “skin planing” procedure he hoped would make his nose more attractive. The artwork’s title suggests the transformative narrative often seen in cosmetic surgery advertisements, highlighting the dichotomy between natural and enhanced beauty.

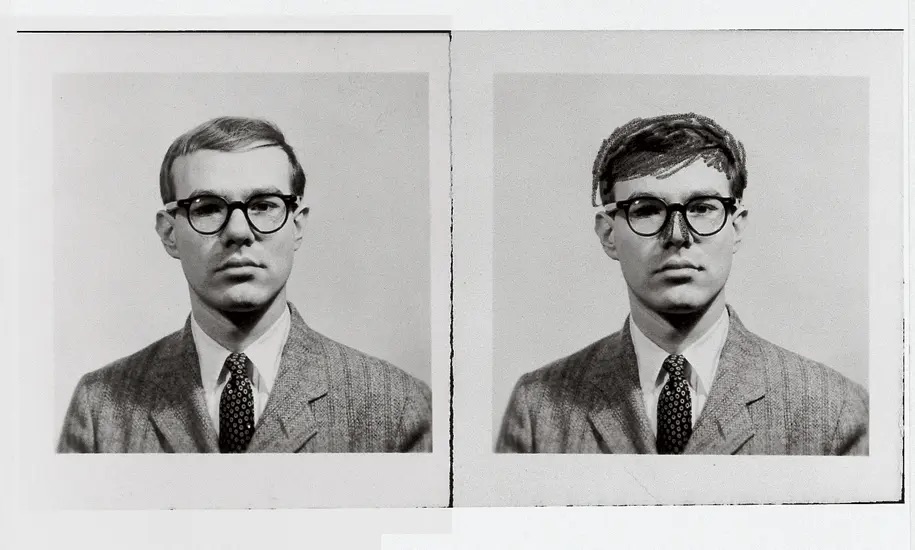

In the context of these artworks, Warhol’s 1956 Passport Photograph with Altered Nose acts as a self-portrait that captures Warhol’s exploration of his insecurities and the tension between his authentic self and the self-improvement ideals of the time. It is both a personal document and an artistic statement, blurring the line between his life and art. Warhol’s manipulation of his image in the passport photo manifests the themes of self-improvement and identity that pervade the aforementioned works, making the photo a poignant autobiographical piece that complements and enriches the narrative of those artworks.

The modified passport photo presents a diptych of the artist, capturing a literal “Before and After” scenario. On the left, we see Warhol unaltered, presenting himself in a straightforward, documentary style typical of passport photographs. His expression is neutral, his attire formal, and his large glasses the most distinctive feature. In the image on the right, Warhol’s appearance is altered, with a hand-drawn addition of hair across the forehead, altering the shape and height of his hairline, as well as the outline of his nose. These modifications suggest an ideal self-image or the desire to conform to certain beauty standards, much like the type of enhancement advertised in beauty and hair loss solutions.

The dual nature of the passport photos—juxtaposing the ‘real’ against the ‘ideal’—foreshadows the commercial aesthetic and conceptual underpinnings of Warhol’s art from this period. It underscores the performative nature of identity and the powerful role of imagery in shaping our perceptions of self and others. Just as Warhol’s early Pop Art drawings and paintings engage with the commercial and superficial aspects of beauty, his modified self-portrait interrogates the authenticity of image and the complex relationship between one’s self-concept and the pursuit of societal beauty ideals. Bald?, Wigs, and Before and After examine the transformation of identity through commercial hair loss solutions and cosmetic surgery, just as this passport photo manipulation reflects Warhol’s own engagement with self-image enhancement.

The alterations in the photo were not only a direct nod to Warhol’s ideal self-image, they reflected the decisive steps which he took in that year to realize it. In 1956, he underwent “planing” surgery on his nose, hoping it would transform his life and appearance, and purchased his first wig. While the results of the nose surgery left Warhol somewhat disillusioned, the wig brought the artist closer to the ideal self-image he had hoped for. Could he have anticipated at the time that this practical hair loss solution would evolve into an iconic part of his legacy?

Warhol’s wigs, which he ordered from hairpiece maker Paul Bochicchio, became an essential part of his identity, both in daily life and in his public persona as an artist. The wigs were made from human hair imported from Italy, suggesting a preference for quality and authenticity in his self-styling. The label inside his wigs, “AN Original by Paul | HAIRPIECE | 147 W. 42 ST. N.Y.,” speaks to the personalized and crafted nature of these objects, which were more than mere accessories; they were integral to Warhol’s self-expression. He kept several at his studio, indicative of the importance of maintaining and curating his image. The fact that Warhol had them glued onto his head points to a commitment to a constructed appearance that was as enduring as it was transformative

The Silver Era: Warhol's Wig Becomes Iconic

In the 1960s, Andy Warhol’s artistic identity underwent a significant transformation, symbolically intertwined with the color silver. Initially, Warhol’s wigs varied in shades from light brown to platinum blonde, but as he embraced the color silver, his wigs also transitioned to a silver-gray hue. This choice wasn’t just aesthetic; it cleverly obscured the aging process, creating an ageless persona, as Warhol had always been “silver-haired” in the public eye.

During this period, Warhol’s association with silver permeated not only his appearance but his artistic works and environment. In January of 1964, Warhol moved his art studio to 231 East 47th Street. This site would soon become his first “Factory,” home to his “superstars.” It became a silver-coated realm under the direction of Billy Name, who Warhol instructed to decorate with “silver” coverings: mirrors, metallic paint, and aluminum foil. This transformation mirrored Warhol’s fascination with the metallic color as a symbol of the future, space exploration, and a nod to the glamorous past of the Hollywood silver screen. Silver represented a convergence of past and future, a theme that Warhol masterfully interwove into his art.

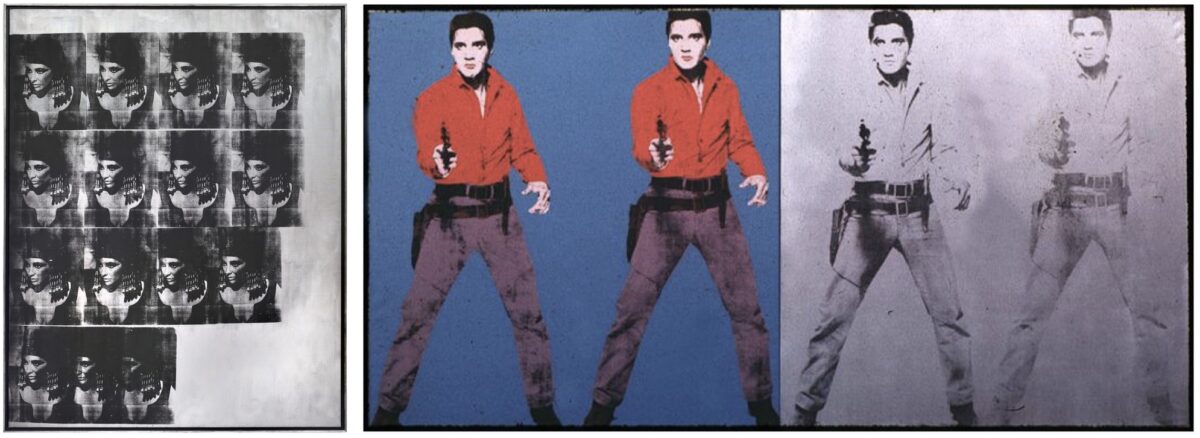

Warhol emphasized silver in his works, notably in portraits of movie stars like Silver Liz as Cleopatra (1963) and in the second panel of his Elvis I and II (1964). These pieces featured repeated silkscreen images of Hollywood icons set against silver-painted backgrounds, combining Warhol’s interest in celebrity culture with his thematic color. This choice was inspired by the silver-coated movie screens of early cinema, which used reflective metallic paint to enhance the projection quality. Warhol mirrored this technique by coating his canvases with silver paint, thereby linking his art to cinematic history. Elizabeth Taylor, depicted in Silver Liz as Cleopatra, personified the allure and tragedy of 20th-century Hollywood, encapsulating Warhol’s fascination with fame and its fleeting nature. Apart from his depictions of celebrities, Warhol used silver backgrounds in numerous artworks during that period, as it reflected his engagement with the complex interplay of mass media and modern life’s most compelling forces.

Warhol’s fondness for silver extended to his “superstar” companions as it did to his creations. He frequently made public appearances with Edie Sedgwick, who mirrored his style by dyeing her hair to match his silver wig, together forming an emblematic Pop Art duo that visually encapsulated Warhol’s artistic themes. In a characteristic play of misdirection, Warhol quipped in a 1966 interview that it was he who was imitating Edie, a statement reflecting his playful engagement with identity and perception: “Edie’s hair was dyed silver, and therefore I copied my hair because I wanted to look like Edie because I always wanted to look like a girl.”

That same year, as the artist announced that he would be giving up painting for film, Warhol’s Silver Clouds installation at Leo Castelli Gallery epitomized his silver phase. These floating metallic balloons offered an interactive experience, continuing Warhol’s exploration of silver as an artistic element.

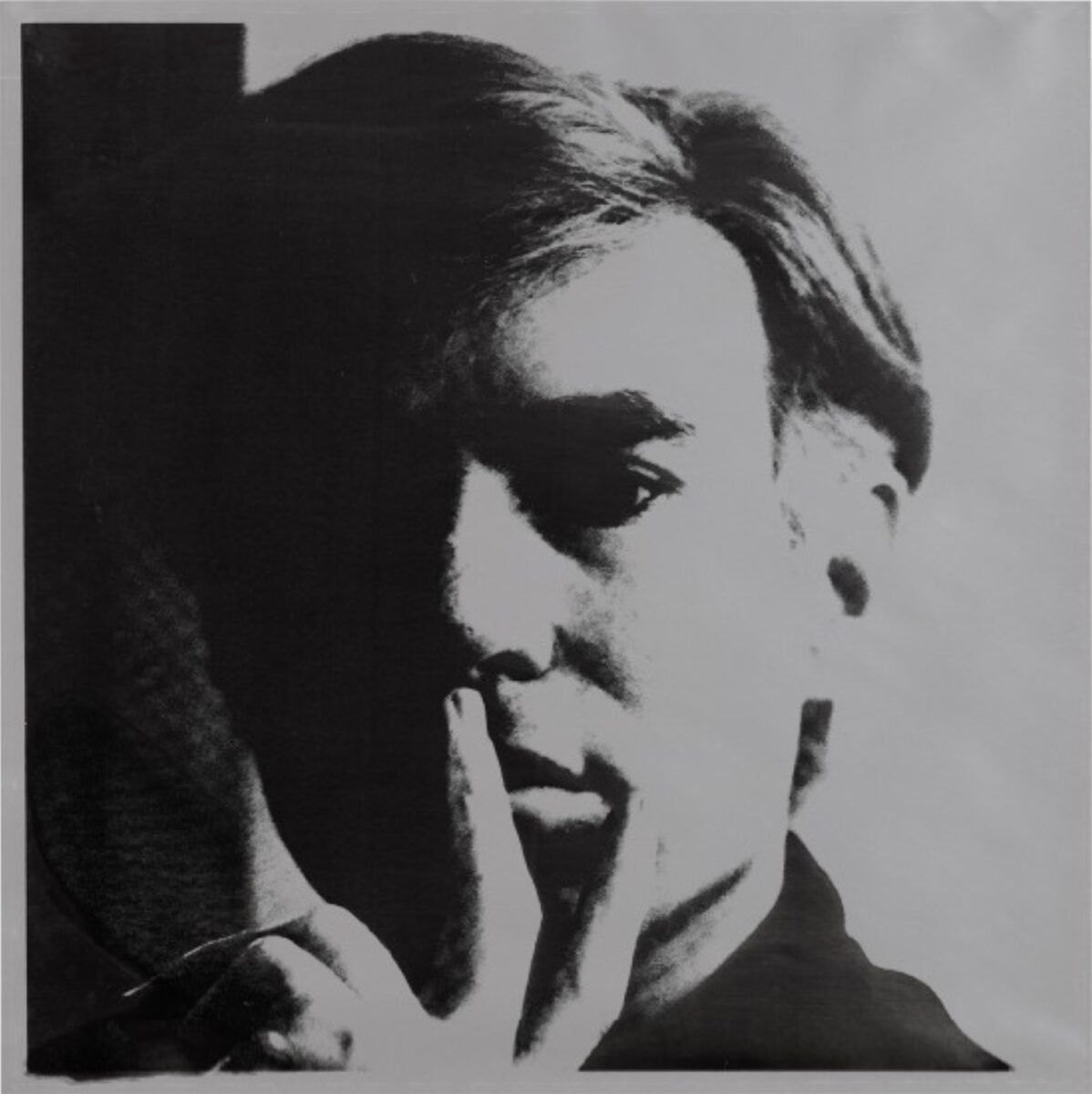

Warhol’s Self-Portrait 16, published to coincide with this exhibition, showcased his art of self-representation. Printed with black ink on silver-coated paper, it featured half of Warhol’s face in contemplation, marrying the introspective with the iconic. This self-portrait, where half of his features were obscured in shadow, ensured immediate recognition; a testament to his status as an artist and a celebrity. His self-portraits, especially those from the late 1970s and 1980s, gained popularity, driven by his experimentation with various cameras and printing methods. These works often featured the silver wig, not just as a personal accessory, but as a symbol of his artistic persona, reflecting his unique identity within both the art world and his iconic stature in popular culture.

The silver wig became so synonymous with Warhol that it even stood in for him on occasion. In a notable instance in 1967, Warhol enlisted an actor named Allen Midgette to impersonate him for an event at the Rochester Institute of Technology. Midgette, who painted his hair silver and donned Warhol’s signature attire, convincingly mimicked Warhol’s look, fooling audiences on several college tours into believing they were in the presence of the artist himself. The ruse continued until 1968 when it was finally exposed. This stunt, which blurred the lines between hoax and high art, provocatively underscored the theme of constructed identity that was central to Warhol’s persona and work.

Adding to the irony, in a 1969 interview, Joseph Gemlis, refers to Midgette as “someone else in a wig who pretended to be you” while describing Warhol in the introduction having “straight, platinum-dyed hair.” This mix-up, where Gemlis inadvertently reversed the reality of Midgette’s real hair, which was painted and powdered for the events, with Warhol’s artificial wig, further emphasizes the profound impact of Warhol’s self-created image on public perception.

The “Silver Era” of Warhol’s career, marked by the iconic silver wig and Silver Factory, represented far more than a stylistic choice. It was a period where Warhol’s identity and artistry converged and evolved, reflecting his engagement with themes of modernity, glamour, and transience. The silver wig, with its metonymic resonance, not only bestowed upon Warhol an ageless quality but also lent him an otherworldly aura, further merging his identity with the themes of his art. Its transformation from a personal solution to an iconic statement was complete when Warhol’s playful manipulations of identity and public perception – from Edie Sedgwick’s silver-dyed hair to Allen Midgette’s impersonation – could blur the lines between reality and artifice. Warhol’s exploration of silver, in both his art and his appearance, thus stands as a testament to his unique ability to blend life and art into a cohesive, intriguing whole.

Celebrity and Camouflage: Warhol’s Mask of Fame

After solidifying his status as a celebrated artist and cultural icon in the late 1960s, Andy Warhol entered a transformative period marked not only by complexity and introspection but also by a distinct shift towards celebrity culture and a more entrepreneurial approach to his art.

The shooting incident in 1968 by Valerie Solanas, which nearly claimed his life, ushered in a period of profound change. Recovering from his wounds, Warhol emerged with a renewed perspective, cultivating relationships with wealthy patrons for portrait commissions, adapting and evolving in the ever-changing art landscape.

Throughout the 1970s, Warhol’s presence became a fixture at various New York City nightspots, such as Max’s Kansas City and Studio 54. Known for his quiet, observant demeanor, his Polaroid camera became an extension of his artistic process, capturing moments that often made their way into his artworks, further blurring the lines between his social life and professional practice.

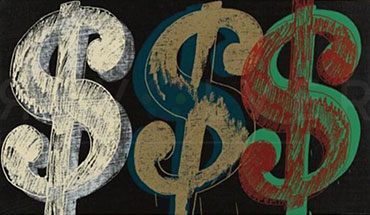

In the 1980s, Warhol experienced a resurgence in both critical and financial success, partly fueled by his connections with younger artists who were leading the robust art market of the era. His friendships with figures like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Julian Schnabel, Keith Haring and David Salle, key players in the Neo-Expressionist movement, brought new energy to his work. However, this period also saw Warhol facing criticism for being perceived as a “business artist,” a label that underscored the commercial aspect of his art practice.

Amidst this backdrop, Warhol’s wigs transcended their initial purpose as fashion accessories and their subsequent function as a symbol of the artist. They served as integral armor for his public and private personas. Their evolution mirrored his own metamorphosis: from an emerging artist grappling with personal insecurities to a cultural icon adept at navigating the intricate dance of fame, identity, and artistic expression. These wigs, now a steadfast part of his identity, served as a mask, a protective layer against the world’s gaze and its unpredictable consequences.

Warhol’s biographer Wayne Koestenbaum explained that “Home was where he glued himself back together: he used the word glued to describe his process of self-repair, which involved literally gluing the wig to his pate.” The practice of ‘getting glued,’ became a metaphor for Warhol’s process of self-preservation, literally and figuratively adhering the wig to his persona. During this time, Warhol, sometimes referred to as Drella – a fusion of Dracula and Cinderella – toyed with concepts of identity and perception, never publicly admitting his reliance on wigs.

Warhol integrated his wigs deeply into his life and work, and treated them as extensions of his body, regularly trimming them as one would with natural hair. This practice extended to visiting the hair salon, where Warhol would have his wig cut, only to appear the following month with a new, longer wig from Paul Bochicchio, playfully suggesting natural hair growth. This ritual was part of Warhol’s complex relationship with his public image, blurring the lines between reality and perception.

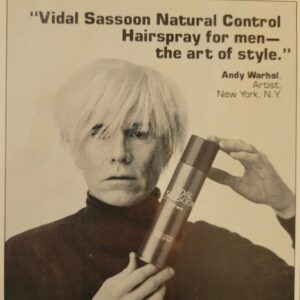

Andy Warhol’s involvement in a Vidal Sassoon advertising campaign that ran from 1984 to 1986 marked a playful twist in his relationship with his wigs. The campaign, known for its tongue-in-cheek approach, featured celebrities known for their distinctive hairstyles, including the bald actor Geoffrey Holder who humorously expressed his wish to use Sassoon products if he had hair. The ironic inclusion of Warhol, whose own hair loss was hidden beneath his iconic wigs, not only highlighted the role his “hair” played in his public persona but also the interplay of reality and artifice central to his life and work.

In becoming the face of a haircare brand, Warhol, once a seeker of commercially available hair loss solutions, subverted his past insecurities while blurring the line between his genuine challenges and his constructed image.

This playful engagement with his image in the Vidal Sassoon campaign was just one of the many significant events that added depth to Warhol’s relationship with his wigs during this phase. A particularly notable incident occurred on October 30, 1985. While Warhol was signing copies of his newly published book America in the Soho area of Manhattan, an unexpected event unfolded.

In a startling moment, a woman abruptly pulled the wig off Warhol’s head and tossed it to a friend, who then fled the store. Warhol vividly recounted this experience in his diaries, expressing his shock and the physical pain of the incident:

"I guess I can't put off talking about it any longer. Okay, let's get it over with. Wednesday. The day my biggest nightmare came true... I'd been signing America books for an hour or so when this girl in line handed me hers to sign and then she - did what she did... I don't know what held me back from pushing her over the balcony. She was so pretty and well-dressed. I guess I called her a bitch or something and asked how she could do it. But it's okay, I don't care - if a picture gets published, it does. There were so many people with cameras. Maybe it'll be on the cover of Details, I don't know... It was so shocking. It hurt. Physically... And I had just gotten another magic crystal which is supposed to protect me and keep things like this from happening..."

This event not only exemplified the public’s fascination with Warhol’s persona but also underscored the vulnerability and the -aspect of his carefully maintained public image. Perhaps the instigator thought this action would give her the 15 minutes of fame that Warhol prophesied for everyone, but her name is not known to this day. Warhol was understandably upset, but didn’t let the assault get the better of him and declined to press charges. The Calvin Klein coat that Warhol was wearing that day had a hood which he used to cover his head while he continued to sign books. This infamous wig-snatching incident further cemented the wig as a symbol of vulnerability and resilience.

Later in his career, Warhol’s framing of one of his wigs as a gift to Jean-Michel Basquiat symbolized a passing of artistic legacy and the intertwining of personal and artistic narratives. Warhol envisioned integrating his wigs into his art, planning sculptures that would use the wigs as a medium, though he completed only the one he gifted to the younger artist. This act blurred the lines between Warhol’s personal artifacts and his artistic creations, underscoring his life as a living, breathing work of art.

The 1970s and 1980s were transformative for Warhol, a time when he consolidated his status as an iconic figure in the art world and popular culture. His wigs, a constant throughout these decades, mirrored this journey, evolving from mere cosmetic accessories to profound symbols of his identity, artistry, and the complex interplay of public persona and private reality. Yet, overlapping this phase of consolidation and fame was a shadow, a turning point that would deeply influence Warhol’s artistic focus and personal outlook.

Contemplating Mortality: Warhol’s Skulls and “Fright Wig” Portraits

In the wake of his near-fatal shooting on June 3, 1968, Warhol’s public demeanor grew more reserved, with an increased focus on the business aspects of his art. This shift was accompanied by a heightened fear of hospitals and illness, influencing his later reluctance to seek medical treatment. This avoidance likely contributed to the complications following his gallbladder surgery in 1987, which led to his untimely death.

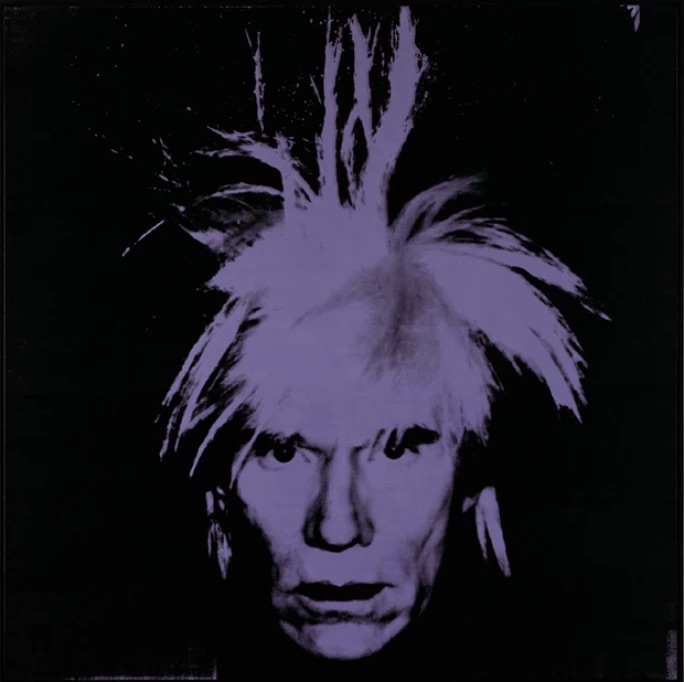

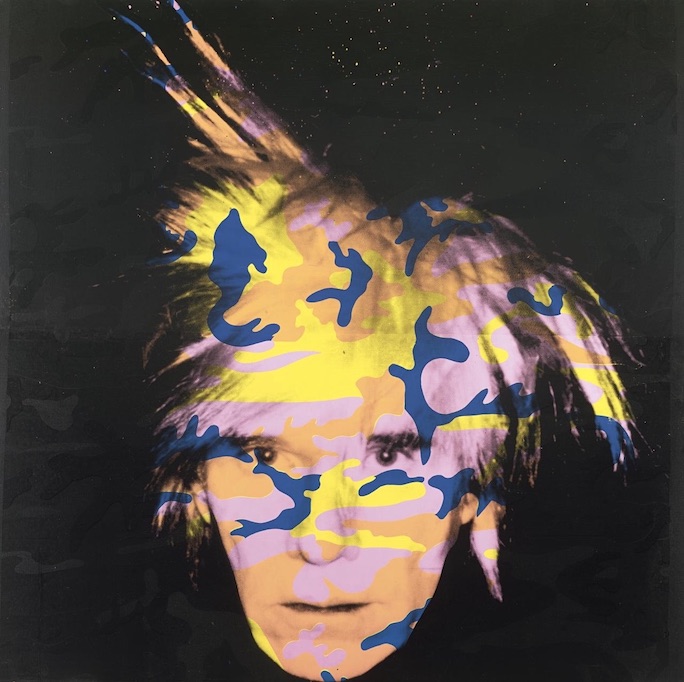

After the attack, Andy Warhol’s artistic trajectory also veered into a profound exploration of mortality and legacy. Warhol’s entire oeuvre, particularly the “Death and Disaster” series, had always flirted with the concept of mortality, but after the shooting his work took on a new depth and turned this contemplation inward. This period of introspection and vulnerability culminated in 1986 with his “Fright Wig” self-portraits; a series diverging sharply from his earlier celebrity-centric works to focus more poignantly on the artist himself.

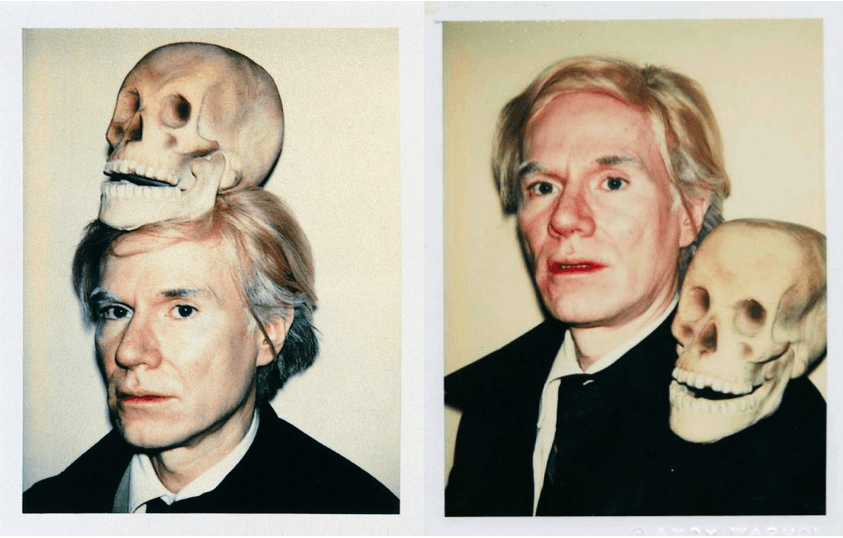

A decade after the shooting, in 1978, Warhol created a haunting series of portraits based on photographs where he juxtaposed a skull with his own image. In these striking compositions, the skull is placed atop or beside his wig, creating a vivid contrast between the symbol of death and his living self. This use of a skull, a long-standing emblem of human mortality and transience in art history, was notably prefigured in Warhol’s 1976 Skulls series, a collection steeped in the “vanitas” tradition of art. The incorporation of this motif in his later self-portraits poignantly captures the fragile boundary between life and death, as well as the interplay between Warhol’s carefully curated public image and his private vulnerabilities.

In a striking photograph from this series, a skull is perched atop Warhol’s head, sitting just above his wig. This placement creates a compelling visual metaphor, with the wig acting as a delicate barrier separating life and death. The skull, symbolizing mortality, appears almost as a crown atop the living artist, blurring the line between the living Warhol and the ever-present shadow of death. Another particularly evocative photo shows the skull resting on Warhol’s shoulder, with his wig swept back to reveal his forehead. This rare exposure of his forehead, typically concealed by his wig, invites a contemplative comparison with the skull’s form. The juxtaposition not only underscores the theme of mortality but also subtly reveals a more vulnerable side of Warhol, often hidden behind his iconic persona.

These photographic explorations of mortality set the stage for Warhol’s later self-portraiture, where his representation of self took on a more introspective and poignant tone. Throughout his career, Warhol managed his public image through many self-portraits, in which his own elevation to the status of pop culture icon reached peerage with those of the glamorous subjects he depicted. This practice of self-reflection reached a profound culmination shortly before his unexpected death in 1986 with the creation of the “Fright Wig” portraits.

These last self-portraits focus entirely on the artist’s face and the strands of hair in his silver wig exploding from the monochromatic background. Among these were two distinct series: one comprising six panels, each characterized by unique coloration, while another set of works integrated the camouflage patterns that Warhol was exploring at the time. The incorporation of camouflage patterns in some of the paintings adds layers of meaning, suggesting themes of defense and concealment. In these portraits, Warhol seems to be shielding himself, using the camouflage as a metaphorical armor against the vulnerabilities of life and the inevitability of death. Warhol is seen peering out from beneath a dramatically oversized wig, his face a ghostly visage against the dark backgrounds. The disembodied frontal pose and sunken cheeks evoke a skull-like image and comparisons to a death mask. The seemingly electrified “Fright Wig” itself becomes a striking symbol of Warhol’s performance of identity, an emblem of the artist’s complex relationship with his public persona and private fears.

The eerie, almost spectral quality of these “Fright Wig” portraits was a profound reflection of Warhol’s contemplation of his own mortality, a theme that had become more pronounced since the shooting. Hung at eye level in galleries, the “Fright Wig” portraits compelled viewers to engage directly with Warhol’s visage, confronting them with their own perceptions of aging and mortality. Created near the end of Warhol’s life, these portraits are a poignant testament to his enduring fascination with life, art, and the inevitability of death. In these works, Warhol seems to be asking the viewer to reflect on his legacy and his own life’s fragility, making these portraits some of the most introspective and powerful pieces of his career. They underscore a journey that began with a violent act, altering Warhol’s perspective and, consequently, the course of his artistic exploration.

The Afterlife of Warhol’s Wigs

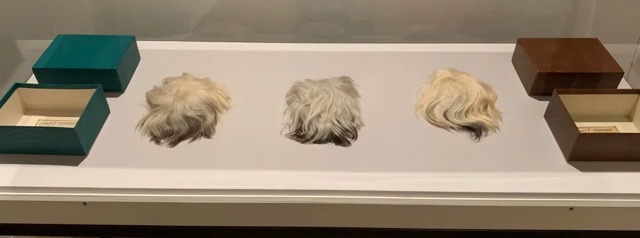

In the wake of Andy Warhol’s passing in 1987, his executors uncovered a trove of personal artifacts, among which were hundreds of his wigs. Stored in boxes and paper envelopes, these wigs bore the marks of their use — the smell of sweat and the stains of glue — tangible remnants of Warhol’s daily life. Their discovery not only shed light on Warhol’s meticulous curation of his image but also underscored the personal value these items held for him.

The posthumous journey of these wigs has been nothing short of extraordinary, paralleling Warhol’s own rise to fame. At notable auctions, collectors have eagerly vied for pieces of Warhol memorabilia, with his wigs fetching impressive sums. For instance, in July 2006, one of Warhol’s wigs was sold at Christie’s for $10,800, far exceeding its estimated value. This fervent interest in owning a piece of Warhol’s personal history speaks volumes about his enduring influence and the symbolic power of these artifacts.

Warhol’s silver wig has evolved beyond the confines of the art world, emerging as a cultural symbol frequently seen in popular Halloween costumes. This evolution from a personal accessory to an iconic emblem captures the public’s intrigue with Warhol, epitomizing the artist’s unique mystique and eccentricity. On the screen and stage, actors like Crispin Glover, David Bowie, Guy Pearce, Bill Hader and Paul Bettany have transformed into Warhol, themselves bearing little physical resemblance to the artist. Yet, donning the quintessential silver wig, they embody Warhol’s persona, illustrating the power and recognition of this simple yet significant artifact.

The Tate Modern’s Andy Warhol retrospective in 2020 further cemented the significance of these wigs in understanding Warhol’s art and persona. The exhibition’s catalogue listed several wigs, highlighting their varied colors and materials, and offering visitors a direct connection to Warhol’s personal world. This display underscored the wigs’ role not just as personal items but as integral components of Warhol’s artistic expression and identity.

The afterlife of Warhol’s wigs is a testament to his lasting legacy. These hairpieces, once part of his daily routine, have become artifacts of immense value and interest, offering insights into the complex interplay of Warhol’s public image, private life, and artistic practice. The silver wig is so synonymous with the artist that putting one on invites its wearer to be a living avatar of Andy somehow. They continue to captivate the imagination, inviting us to explore the many layers of one of the 20th century’s most influential artists.

Now, one of these artifacts lives at Revolver Gallery. It’s a poignant piece of Warhol’s legacy; a silent witness to the enduring influence of an artist who redefined the boundaries between personal identity and artistic expression. From the early years of self-doubt and his active engagement with self-improvement ads, to the iconic Silver Factory era, his wig styles mirrored and then became synonymous with his artistic identity. Once Warhol was firmly established as an art world icon, he used his wigs as armor, consolidating his image, navigating fame and personal trials with resilience and flair. With the haunting “Fright Wig” self-portraits, Warhol’s hairpieces proved to be more than adornment, but integral to his persona and artistry. The afterlife of Warhol’s wigs, from their posthumous discovery to their revered status in auctions, exhibitions and popular culture, further cements their significance in understanding the enigmatic artist.

At Revolver Gallery, the acquisition of Warhol’s last wig – the “death wig” – is not merely an addition to our collection; it’s a continuation of the narrative that Warhol himself crafted so meticulously throughout his life. This wig, a symbol of Warhol’s final chapter, invites viewers to reflect on the fragility and profundity of an artist who was as much a creator of his own mythos as he was of his art.

Sources:

— ‘Andy Warhol’s Wig – a defining art object’, Hair is for Pulling—Blogspot, 10 October 2011, <https://hairisforpulling.blogspot.com/2011/10/andy-warhols-wig-defining-art-object.html>

— ‘Meditations of Andy Warhol’s Fright Wig,’ Artvisor, 21 July 2022, <https://www.artvisor.com/meditations-on-andy-warhols-fright-wig/>

— Bradford R. Collins “Dick Tracy and the Case of Warhol’s Closet: A Psychoanalytic Detective Story” American Art, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Autumn, 2001), pp. 54-79 (26 pages) <https://www.jstor.org/stable/3109404>

— Sydney Contreras “Andy Warhol: Person vs. Persona”, Revolver Gallery, 31 August 2021 <https://revolverwarholgallery.com/all-about-andy-warhol-person-vs-persona/>

— Kenneth Goldsmith (Ed.), I’ll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews, 1962-1987 (Carroll & Graf Publishers, New York: 2004).

— Blake Gopnik, Warhol (HarperCollins Publishers Inc., New York: 2020).

— Cynthia Green ‘Silver Wigs, Floppy Hair and Ray Bans–Andy Warhol’s Self-Image’ The Voice of Fashion, 27 September 2019, <https://www.thevoiceoffashion.com/intersections/famous-wardrobes-then-and-now/silver-wigs-floppy-hair-and-ray-bansandy-warhols-selfimage–3156>

— Tate Modern Exhibition Guide — Andy Warhol

<https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/andy-warhol/exhibition-guide>

— “Louis Armstrong’s Tape Recorder/One-Cent Magenta/Andy Warhol’s Wigs.” History’s Lost and Found, created by the History Channel, Atlas Media Corporation, 1999.