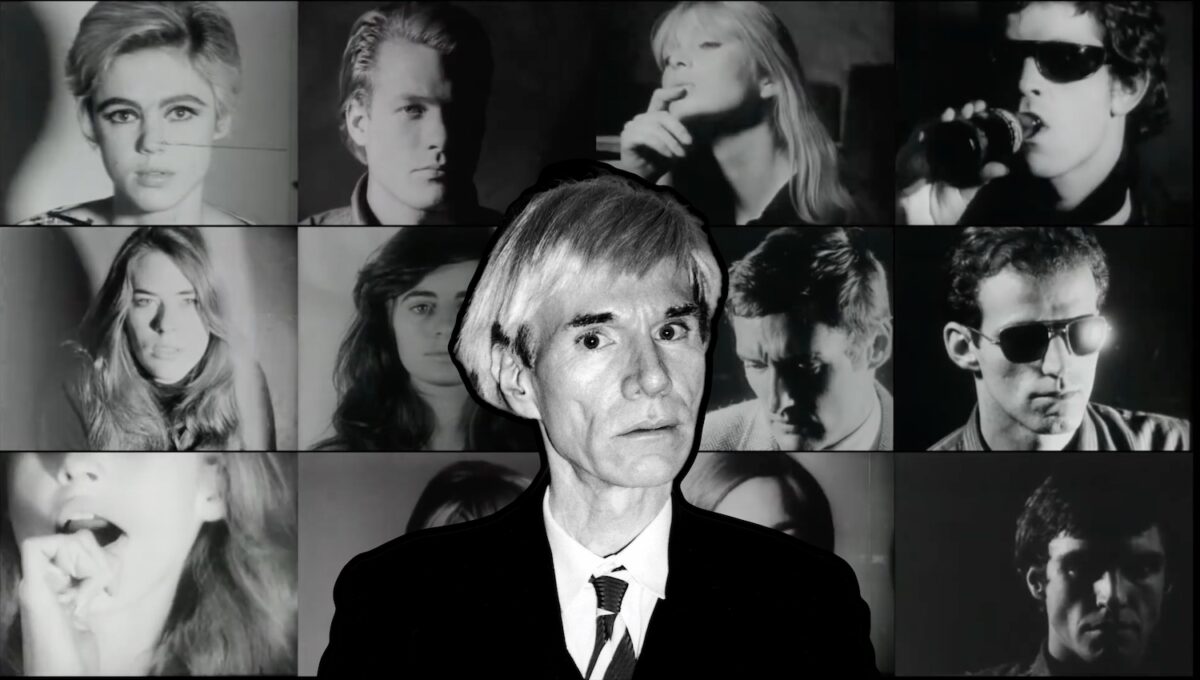

Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests, conducted between 1963 and 1966, stand out as a defining contribution to the avant-garde cinema movement. Warhol created nearly 500 of these enigmatic short films, which feature the notable faces of figures like Dennis Hopper, Bob Dylan, his muse Edie Sedgewick, and The Velvet Underground’s Nico and Lou Reed, as well as the not-so-famous misfits, visionaries, and rebels who frequented his Factory studio. He dubbed these eclectic personalities “Superstars,” regardless of their fame outside the studio walls. At that time, these subjects were mere newcomers to Warhol’s Silver Factory Studio, completely unaware that these original “selfies” would explore where identity can be fashioned—even fabricated—and foreshadow the idea of fame in the digital landscape as we know it.

Although we are living in the age of YouTube and instant digital access to streaming services, the majority of the Screen Tests remain out of reach for the general viewing public. They have been preserved and carefully stored through the team efforts of the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Yet their resulting elusiveness only amplifies their allure and significance in our media-saturated world.

For this reason, it feels destined when these rarely viewed films resurface in timely exhibitions, and most recently at Christie’s in Los Angeles, coinciding with Frieze Week, from February 27 to March 14. The location was fitting: Where better to hold a vigil for the unapologetic celebrity enthusiast’s films than the ‘City of Stars’ itself? Unlike traditional movie theater displays, Christie’s presented the Screen Tests in a dramatically immersive environment, projecting them floor-to-ceiling on each wall of the gallery space, offering viewers an enveloping experience of Warhol’s vision. Alex Marshall, Christie’s Senior Specialist in Post-War and Contemporary Art, remarked in the exhibition’s press release, “Across all mediums—painting, photography, prints, and films—Andy Warhol was inarguably a master of portraiture.” And it’s true—Warhol’s Screen Tests are the most intimate form of portraiture you can get.

The recent, rare exhibition of these living portraits by Christie’s and the Warhol Museum invites us to do more than revisit them; they raise questions about the lasting impact of Warhol’s experimental work against the backdrop of contemporary visual culture. What is it about Warhol’s Screen Tests that are so captivating? How have they managed to continue garnering interest in the present day? Why did Warhol make them in the first place, and what can be said about them now, amongst our current landscape of varied visual art and social media? Here we’ll try to unpack the enduring significance of Warhol’s work along with its profound commentary on the nature of celebrity, identity, and the voyeuristic lens through which we view them.

Warhol's Screen Tests: What Were They?

“Sit still.”

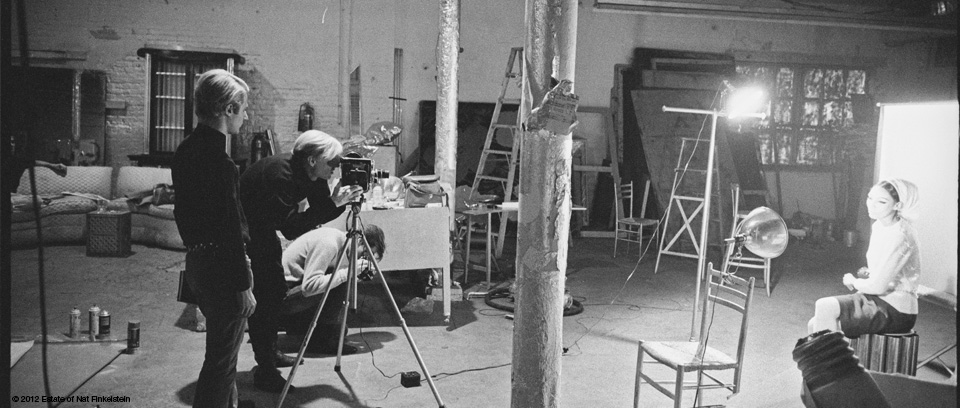

This simple directive from Warhol under the bright studio lights, prompted his subjects to remain motionless, allowing for a rudimentary portrayal of their state. It was an invitation into vulnerability, freedom from the affectation of their curated public facades.

The screen tests worked like this: Warhol’s subject came to sit in front of a 16mm Bolex camera shooting at 24 frames per second (fps), later slowed to a projection speed of 16 fps, putting most of the clips to approximately 4 minutes. As a result, the screen tests have the quality of being stuck in a time loop full of people who spellbind the viewer, and who are immortalized in Warhol’s gaze. These films—rendered in stark black and white using Kodak Tri-X film, and devoid of sound—were a jarring foil to his loud, Pop Art concoctions.

Unlike Hollywood’s conventional screen tests, which are intended to assess the chemistry of the actor with a scripted character or another actor, Warhol’s direction (or lack thereof) stripped away these elements to assess a subject’s chemistry with the camera itself. By placing limitations on movement and sound, he focused on the raw, unmediated presence of the individual before the camera. This approach turned the camera into a silent observer, capable of capturing the subtlest microexpressions, only just detectable due to the reduced pace of the projection.

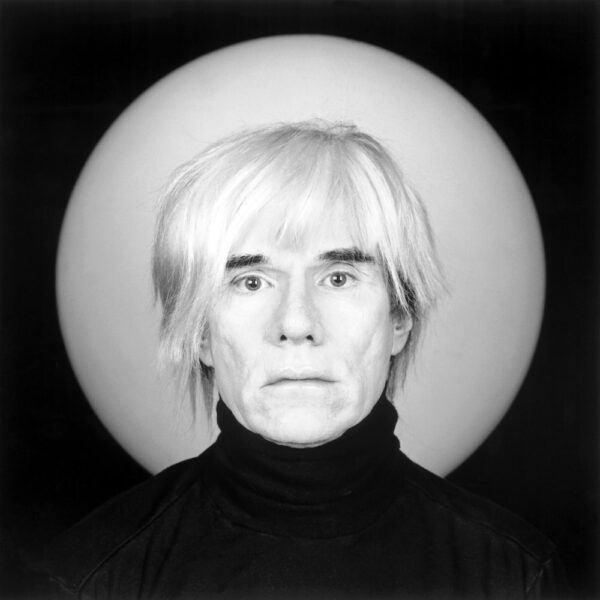

In this slowed-down, introspective space, the Screen Tests transcend mere visual records, becoming something more elusive to define. Warhol identified this quality as “aura,” which he elaborated on in his book, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again), “When you just see somebody on the street, they can really have an aura. But when they open their mouth, there goes the aura. ‘Aura’ must be until you open your mouth.” It’s no surprise, then, that Warhol’s Screen Tests are silent, suggesting that the true essence of a person is most palpable in their silent, unguarded presence.

By rendering these tests in silence, Warhol not only preserved the “aura” of his subjects but also radically diverged from the traditional objectives of portraiture and cinema. Where classic portraits and films seek to capture or convey a narrative and the star quality of the actor’s performance, this “aura” embodies a different form of glamour. It isn’t the colorful, stylish, party kind that Studio 54 held, or the diamond-ring, pink gown Marilyn Monroe kind that makes you want to revisit Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. By stripping away all performative social tendencies of his subjects, the “aura” strand of glamour comes in a raw form, as an innate star quality that shows itself in stillness. The Screen Tests made their subjects into “Superstars”—the living, breathing art pieces who embodied Warhol’s avant-garde vision to challenge American ideas of fame.

Warhol also believed that “‘aura’ is something that only somebody else can see, and they only see as much of it as they want to. It’s all in the other person’s eyes.” Knowing that the perception of identity is subjective, Warhol manipulated the conventions of film to place his subjects at the center of his gaze and allow viewers to quietly and viscerally experience the aura through his eyes. In doing so, his minimalist approach, focusing purely on the individual’s interaction with the camera, anticipated future movements in both art and film that would similarly seek to strip down to the essence of their subjects. Watching them challenges viewers to reconsider the nature of celebrity, the act of observation, and the relationship between the viewer and the viewed.

Warhol's Gaze: A Mirror to Society

Warhol’s penetrating gaze upon society observed the dual roles we inhabit as both victims and perpetrators of commodification, and his boundary-pushing experimentation with art mirrored this view exactly. His works, such as Campbell’s Soup Cans and Brillo Boxes were point-blank appropriations of products that were already popular, yet they became some of the most coveted, high-selling works to this day, obliterating the divide between commercial and fine art. Warhol understood the power of consumerism: the compulsion to embrace the superficiality of commodities, flipping this on its head to challenge the boundaries of art.

This critical lens, Warhol’s gaze, extended with particular intensity to the realm of celebrity. His portraits and films crystallize famous individuals as emblems of our collective interests in fame, money, sex, and beauty; the depictions are striking for their ability to elevate their image to the status of cultural icons and make them aspirational avatars on every front. And we, society, buy into our fantastical perceptions of pop culture. How could we not? So did Warhol, which is why he used Screen Tests to strip it all away, effectively challenging common perceptions of celebrity entirely. These representations, far from being passive depictions, acted as a mirror to society’s obsessions; projections of pop culture that make us question our role in the cycles of consumption and idolatry that define contemporary life, making his exploration of commodification and celebrity as relevant today as it was in his own era.

Warhol’s “Factory” proved itself worthy of its industrial moniker over the course of his meteoric career, but this is especially true of his Screen Tests. His methods mimicked the fast turnover of postwar industrialism, and his spidey-sense for trendspotting enabled him to manufacture his own trends by channeling the power of a consumer-driven society. The so-called “beauties” who walked through his Silver Factory doors for a screen test became subjects to Warhol’s discerning, culture-attuned gaze. Their Screen Tests were initiation rites that would propel them from partygoers and socialites to starlets and supernovas, repackaging their popularity as a source for cultural fascination, obsession, consumption. Those who were chosen represented Warhol’s vision for the future of media and art—Warhol’s celebrities, anointed by his Midas’ Touch.

Within these Screen Tests, a raw vulnerability is palpable—from the subtle twitch of Edie’s mouth, to the over-oscillation of Lou Reed’s Adam’s apple after he takes a sip of Coke. There’s a sensual layer to the attempt at honesty, akin to the first moment someone bears it all. This vulnerability is most striking in the haunting stillness of Ann Buchanan, whose Screen Test is a powerful exposition of Warhol’s directive to “sit still,” taking it to an almost unbearable extreme. Buchanan sits motionless, barely blinking, her gaze penetrating the viewer as a single tear rolls down her cheek, embodying a profound emotional depth that transcends the frame. This moment, perhaps more than any other, captures the essence of vulnerability and the complexity of human emotion under Warhol’s unyielding gaze. Unlike Edie Sedgwick or Lou Reed, whose fame reached beyond the confines of the Silver Factory, Buchanan’s notoriety is almost solely tied to this poignant screen test, suggesting an inadvertent layer of cruelty in Warhol’s command. Her presence on camera—so raw and unguarded—challenges the viewer to confront the emotional weight of observation, making her Screen Test a deeply affecting illustration of beauty and sorrow intertwined, and a poignant commentary on the fabrication of fame.

The Screen Test Legacy: Echoes of Warhol's Vision in the Digital Age

All of these details are made visible only with the slowing of the projection, creating a voyeuristic perspective that intensifies the longer the subject fights the urge to move. This voyeuristic quality echoes throughout Warhol’s films, notably in Sleep and Kiss, both of which he strips down to the bare bones of cinema and people doing regular, ordinary people things as if watched through a window (or in Kiss’s case, a microscope that captures the mechanics of kissing without leaving anything to the imagination). These evocative portrayals, with their focus on the intimately mundane, predate the sensory immersion of our modern-day ASMR channels.

Warhol understood performance as a social construct because he was a performer. His curated style and careful responses are unmissable even in his few on-camera interviews and affirmed by nearly anyone who’d ever met him, which might be why voyeurism is so ingrained in his works. Warhol’s obsession with watching the veneer of perfection break was so great that he invented artistic practices like his Screen Tests to chip away at it himself. The fascination with the facade versus the authentic self underpins Warhol’s pioneering role in the exploration of voyeurism as an artistic lens.

As a society, we are much closer to Warhol’s form of voyeurism than we would like to think. Warhol’s experimentation in this naked, unembellished cinematic style forged the path for today’s “Instagram dumps” and reality TV shows. The habit of scrolling through social media, engaging in what’s known as “creeping,” is a widely accepted spectator sport, motivated by a compelling urge to compare ourselves against the constructed identities of others. Yet, where Warhol’s minimalistic experiment sought the essence beneath the exterior, the modern media milieu is wrought with overstimulation and the impossible challenge of discerning the lines between genuine and performed acts. Current media walks the tightrope between authenticity and performance, fully aware of its influence and potential impact all the same. The Screen Tests in their simplicity and directness invite us into a reflective examination under Warhol’s gaze, acting as a societal mirror that probes the nuanced play of identity in a world increasingly dominated by the curated showcases of social media, offering a critical perspective on the constructs that define and dominate our perceptions of self and others in the digital age.

Warhol recognized the transformative potential of film for crafting moving portraits, offering an immediacy and specificity that was impossible to truly harness by any other means. For those invited to the mythic Silver Factory for their close-up, it symbolized Warhol’s personal admiration for them—or at least their potential for fame. For some, a Screen Test at Warhol’s studio was the beginning of their big break. For others, it was their first and last project. But whatever the outcome, Warhol’s moving portraits went beyond just capturing the physical likenesses of their subjects. He realized their complexities and magnified their energy, emotion, and inner life by simply placing their subtle, nonverbal mannerisms in the spotlight. Much like his iconic canvases of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley, Warhol’s films serve as mirror reflections for the drama, glamor, and mortality of his subjects. Yet, his Screen Tests leave you with a distinctly different impression of being watched back… and you’re dared to look away.

Today, millions of internet-permanent, moving portraits are uploaded to platforms like TikTok and Instagram, with millions of wide eyes ready to receive them. Some of these are glam-makeup tutorials, skits, or dances, while others are educational, or entirely unexplainable in their content. Even before this new kind of moving portrait, the “selfie” dominated social media timelines. The proliferation of so many images, so intimate in their visual content and the nature of their production—shot on personal devices by, and inside the bedrooms of, the subjects themselves—is both an evolved form of Warhol’s Screen Tests and a far cry from them. If the artifacts of selfie culture and social media posts represent hand-picked, manicured moments from the lives of their subjects, who post them in pursuit of designing their public persona, Warhol’s Screen Tests strip away artifice, presenting individuals in unvarnished truth, free from the constraints of self-curation. Warhol’s gaze refuses to mask blemishes, omit imperfections, or cut the bloopers, constructing public persona in a way that is independent of the subject’s own ideals. His command to “sit still,” annihilates any remnants of performance and manufactured self-imagery, seeking to present the self exactly as it is.

In the hyper-digital age, Warhol’s Screen Tests are an uncanny time capsule that reflects the future he predicted. More than ever, society is fascinated with identity, wielding advanced tools to control perception, often to a fault. Now, with the mere accumulation of likes and reposts, celebrity status can be achieved overnight, and virality in hours. The recent showcase of Warhol’s work at Christie’s Los Angeles acts as a crucial revival of his visionary insights, rekindling an awareness of his profound impact on perceptions of fame, identity, and the art of portraiture. This exhibition not only reintroduced Warhol’s genius to a new generation but also invites us to reflect on our individual and collective roles in the construction and recognition of stardom, urging a deeper engagement with the legacies we choose to celebrate and perpetuate.

Exchanging the pristine gleam of his subjects for a hauntingly natural quality, Warhol’s Screen Tests inarguably make up some of the most authentic moving portraits that exist in modern art. Warhol captured the essence of his time before phones and cameras became parasitic and gave way to a hyperconscious sense of self-presentation. They do not simply document a moment with a subject before a camera; they invite a deeper engagement with the concept of presence itself, marking a significant innovation in the understanding and representation of people in art. Warhol’s inquiry into what constitutes true star quality—beyond the superficial trappings of fame—the makeup, the clothes, the readiness to smile and blow a kiss—invites us to consider the foundational elements of celebrity in a new light. Perhaps for Warhol, it was the negation of these things that makes a star; the ability to endure the silver screen vulnerably, without performing for the camera.