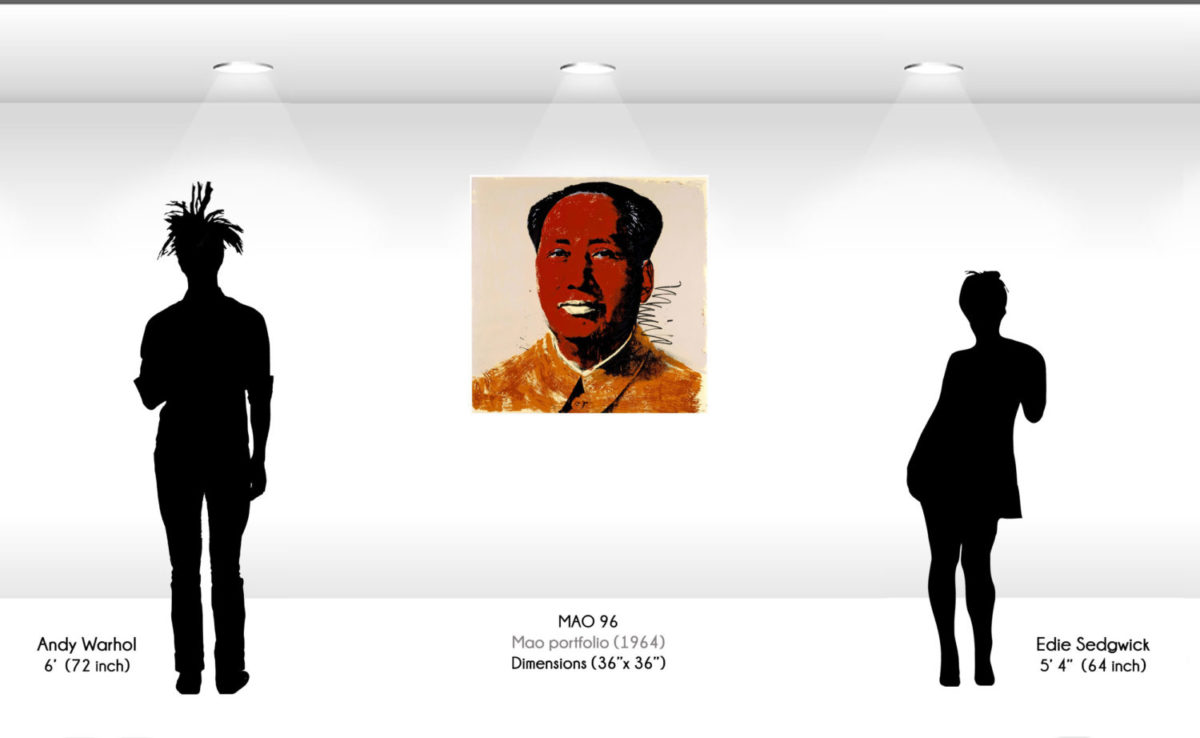

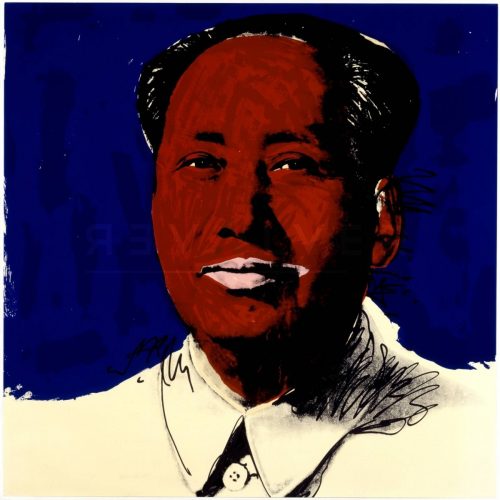

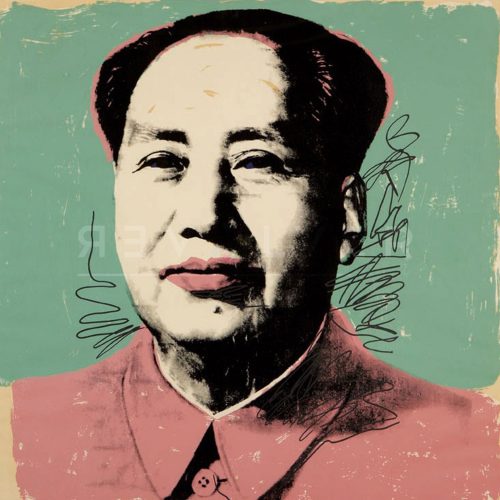

Mao 96 is a screen print by Andy Warhol included in his Mao series from 1972. It is sometimes simplified as the “red Mao” in reference to the subject’s face. Considered alongside Warhol’s usual manipulations of celebrity portraits, consumer items, or his infamous superstars, Mao is an interesting interception of his traditional subject matter. It is perhaps Warhol’s most controversial series, considered as such by many people in both the West and the East. He published the series in 1972, soon after president Nixon returned from his trip to China.

Andy Warhol was a man of contrasts. Obsessed with fame yet shy in person, willing to film and depict sexual themes yet purporting to be celibate, from a poor background yet enthusiastically celebratory of wealth, it’s fitting that one of his most well-known reflections is an oxymoron: “I am a deeply superficial person.” But Warhol’s deepest and most thought-provoking contradictions are perhaps most interestingly expressed in his controversial depictions of communist leaders, such as in Mao 96. In these prints from 1972, Warhol, a man fascinated by capitalism, wealth, and consumerism, took the signature style of commodified representation with which he approached such figures as Mick Jagger and Marilyn Monroe and applied them to the images of capitalist culture’s most ardent and powerful opponents.

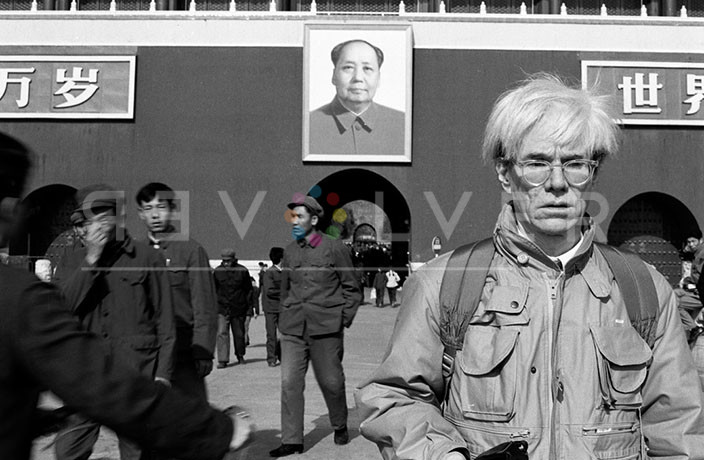

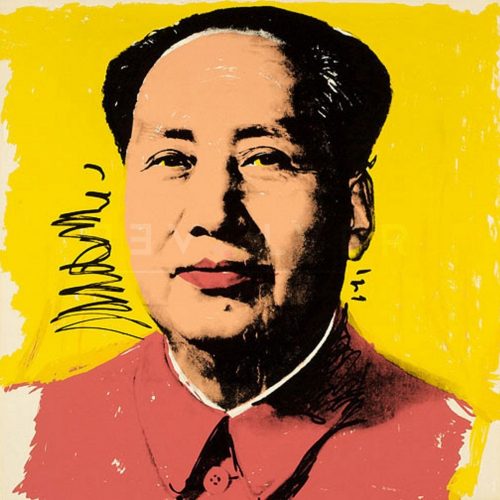

Warhol viewed himself as an entrepreneur as much as an artist. So why did he produce prints of the ideological enemies of individual entrepreneurship? Before he even published the Mao series, Warhol said of communist China, “they don’t believe in creativity. The only picture they ever have is of Mao Zedong”. Warhol, whose work famously covered groceries, symbols, and celebrities, must have found this austerity of imagery in China bizarre. Yet, in Mao 96, Warhol not only depicts the Chinese leader, but he does so with imagery directly borrowed from the very Chinese propaganda he decried earlier.

Warhol’s portraits generally reflect a fascination with celebrity, insofar as celebrity is the commodification of identity. The irony of giving a communist leader this treatment may be intentional. By giving Mao Zedong the celebrity print treatment, Warhol’s philosophy absorbs even its ideological opponents. But Warhol’s depiction of Mao may run even deeper. Warhol described the “only picture” of Mao Zedong as “like a silkscreen”. Indeed, Warhol used a Chinese picture as the basis for this print. In the series, Warhol bridges the gap between Chinese propaganda and silkscreen. Perhaps this demonstrates not only Warhol’s contradictions, but the irony of Mao himself. Mao’s ideology completely contradicts Warhol’s. However, his government mass-produces an image of him that translates easily to Warhol’s oeuvre–as a celebrity, no less.

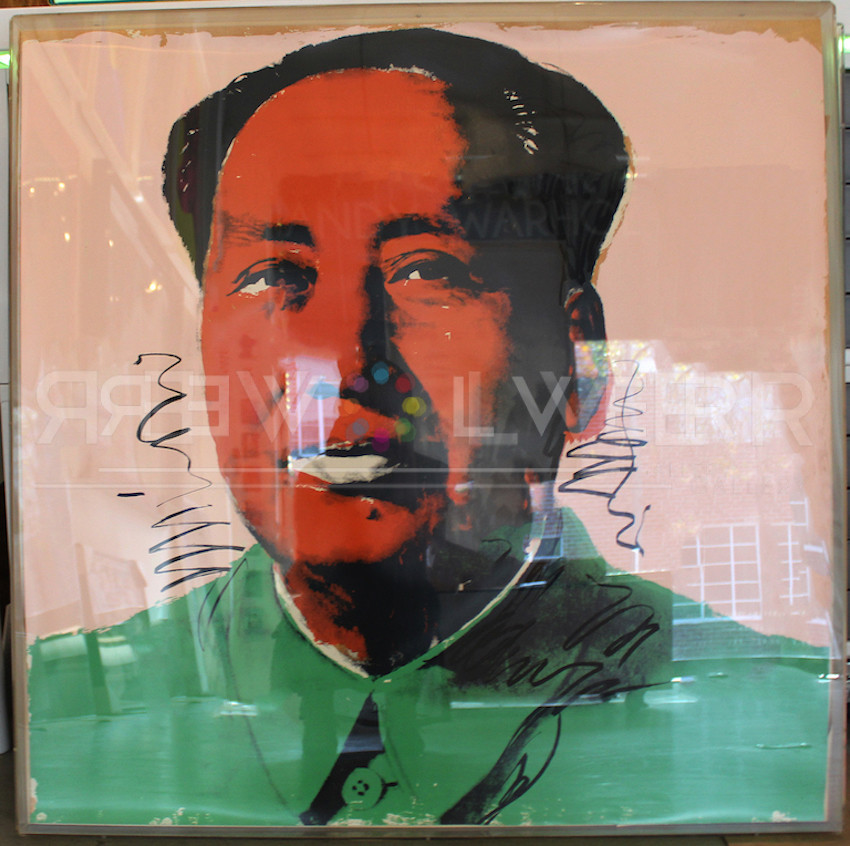

Of course, Warhol’s unorthodox use of color separates his silkscreens from the socialist realism of Mao’s original propaganda picture, and Mao 96 is certainly no exception. Unusually, Warhol understated the background, and realistically shaded the jacket. But Mao’s deep red face sets this print apart. The colorless lips make the red shading appear as a layer of makeup, giving Mao an otherworldly look. The red itself has undeniable connotations with communism, suggesting that Warhol’s ability to incorporate Mao’s ideology into his unmistakably commodified depiction. Ultimately, Mao 96 diversifies Warhol’s catalogue, and appears as one of his most interesting works.