Andy Warhol was an artist of appropriation. Known for calling our attention to unexpected images and objects, he had a knack for making ordinary things appear obscure and intriguing. Although his celebrity portraiture and emphasis on recognizable signs and symbols characterize a large portion of his work, Andy was inspired by a variety of subjects in his screenprinting, painting, and photography. Oftentimes, his artworks are made recognizable not only by their flamboyance, but by the attention devoted to the singularity of their subjects.

The diversity of his inspiration led Warhol to dabble a fair amount in still life (or encounters with subjects similar to those often found in still life paintings). Although he sometimes chose traditional subjects, a Warhol “still life” is marked by the artist’s propensity to experiment with the form and definition of the subjects that occupy his prints.

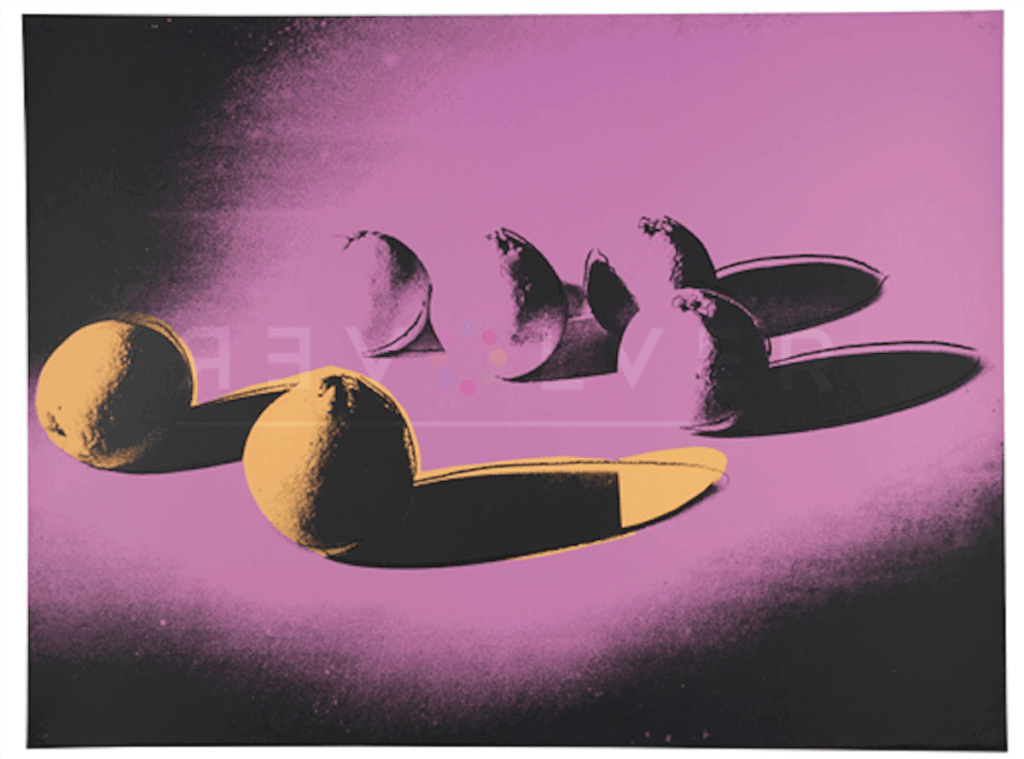

A still life is a painting of several objects: usually fruit, flowers, and other commonplace, inanimate items, rather natural or synthetic. Warhol’s Space Fruit series comes to mind most immediately. But in a more general sense, many of Andy’s prints evoke the placid nature of the still life genre, insofar as they present idle objects in a state of mere existence.

Consider the Campbell’s Soup Can, one of Andy’s most famous works. The picture of the soup can, though intentionally lacking the slightest contextual detail, slides towards the realm of Still Life, as a quaint object captured by the artist, perhaps on the counter in one’s kitchen or on a shelf in the pantry. An ordinary household object presented with no frills, no extraneous detail to obscure its nature. If the Campbell’s cans are Andy’s most “pure” versions of still life, then this opens up many more of his works for consideration, allowing us to ponder the relationship between still life and Warhol’s pop art, as well as how the genre may inform his own work.

Object Photography

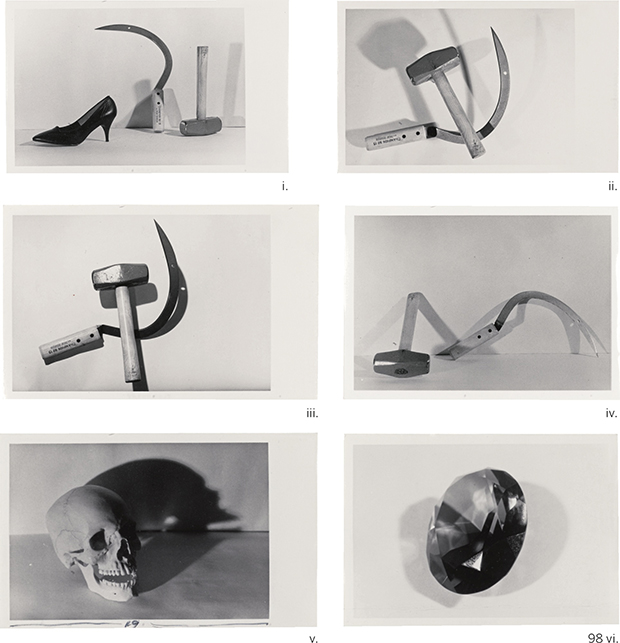

The Hammer and Sickle, Skulls, Shoes, and Gems series all deserve a spot in the Warhol still life canon. Being photographed by Warhol (or one of his assistants, like Ronnie Cutrone), portfolios like these show Warhol using still life photography as a means to create Pop Art.

By capturing the essence of an object in a photograph, then enlarging it, silkscreening it, and splitting it up into layers to be meddled with unnatural color and contour, Warhol alienates the objects from their proper context entirely. Still, the final product appears to maintain the precise essence of the original subject, perhaps even illuminating it through this process of obscuration: does an object become more pure, more comprehensible, once it is freed from the context that holds it in place?

In Warhol’s Space Fruit: Still Lifes series, nature becomes explicitly alienated from its origins. Quite literally items of consumption, Andy’s “space fruits” are centered as bizarre, alien species through this over-styling of fruits, which are now suspended in colored space. Indeed, these fruits are already mass-produced by farms and farmers across the country and the whole world, so Andy’s radical re-imaginations of their appearance serves as a new “spin” on well-known, common commodities. By making them “space fruit”, Andy not only casts them in a new light– he makes them new for consumers, increasing their appeal and intrigue. They become hot new items, reinventions for the purpose of consumption.

Nature

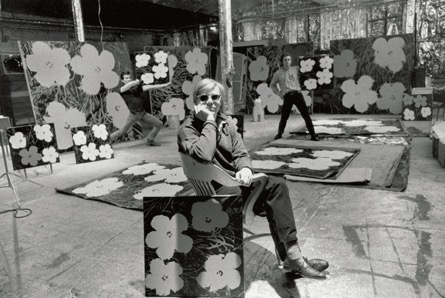

One of Andy’s most well-known print and painting projects, Flowers, could be inspected through the “still life” lens as well. The flowers, painted in full with bright and pastel colors, lay on more sharply-defined yet duller beds of grass, each long blade delineated underneath the flowers. Knowing that Andy used Patricia Caufield’s photograph as the source-image for the series, the framing of the four flowers in the prints certainly echoes the common sensibilities of photography, where a single object can dominate the view as a way to center and glorify it. (Still Lifes, too, often appear like photographs, as snap-shots of life.)

In Flowers, nature takes up the entirety of the print, yet we are treated to a mere caricature of a single aspect of nature: the flowers. They are beautiful, yet clearly not real. But in a world where fake flowers are given out and sold alongside freshly-picked bouquets and seasonally-planted specimens, what is “real” becomes less relevant. Andy’s depiction of these flowers further romanticizes one of nature’s most revered creations, emphasizing and distorting their visual appeal with Pop Art colors, while also putting their true value and purpose into perspective for the viewer.

Andy’s Kiku series draws further attention to the beauty of flowers as the subject, choosing this time to represent them purely as colorful outlines. This again draws attention to the visual appeal of the flowers while moving away from realistic reproduction. In doing so he subordinates nature to the style and purposes of pop art, recreating these representations of nature’s beauty in a simplistic, commercial manner.

One might ask: as a commercial artist, does Warhol’s use of still life blur the line between the traditional genre and commercial photography?

In a more interesting example, Warhol’s Gems series took products of natural processes, precious stones, and stylistically recreated them in prints. In a way, this had the effect of dulling the natural beauty the gems were known for, by transposing them to screen and detailing them in ways reminiscent of but not exactly as the gems behave in real-life. Here, Andy’s manner of depiction serves as an equalizer– though the gems may have high market value and aesthetically-lauded, they too become just further stylings of pop art sensibilities. They are reduced to caricature, captured in a recognizable yet tragically two-dimensional way, reduced to lines and colors resembling reflections and mere facets.

This effect of equalization is hardly more pronounced than in the Electric Chair series. With such a grim subject, it is hard to construe the subject as anything less or more than what it is. Andy’s variants of the print do much to preserve the anxiety and misfortune associated with the chair, but his bold re-coloring reminds the audience that perspective is variable.

There is but a chair, sitting in the middle of a room, with its cord trailing out of the frame. Though the shadows indicate a sinister, somber mood, Andy’s re-colorings of the entire image bring attention to the scene and not the object.

By doing so, the chair becomes inseparable from its context (unlike the previously considered soup cans and Space Fruits). But, true to the roots of Warhol’s Pop Art method, context is turned on its head when the image of the electric chair is displayed in an art gallery. After alienating it from the newspaper and the television screen, where images of death and disaster regularly circulate, audiences can digest the electric chair again, almost for the first time. Its existence as an object of death becomes subject to further contemplation, and we are re-sensitized to its inherent violence after confronting it in an unexpected setting.

Though several of Andy Warhol’s still life adjacent works may not portray the genre’s more archetypal subjects, still life contributes massively to Warhol’s style, technique, and sensibility. From flowers, to trucks and communist symbols, Andy’s use of still life strikes a healthy balance between common, ordinary items and objects of deeper contemplation like skulls and weapons, bringing newer, fresher attention to them by way of his pop art manipulations.

Warhol’s co-opting of the still life form makes many of his artworks possible, and is responsible for the deep conceptual mood of his art. The artist’s method of portrayal followed by manipulation allows him to elevate certain objects to encourage deeper appreciation, while debasing others to invite a critical gaze. Rather than starting from scratch on a blank canvas, Warhol uses object photography or an appropriation of a readymade and still image to achieve this end.

The result is a form of Pop Art that re-opens the world and allows us to see objects—rather mundane, beautiful, or terrifying—in a different way. By blending the glorification of the still life form and the idiosyncratic re-envisioning inherent to Pop Art ideals, Warhol’s art becomes increasingly meaningful, and his legacy is made glaringly apparent.