"If somebody faked my art, I couldn't identify it."

Andy Warhol

When Andy Warhol passed away, he left behind a single, eleven-page will. He also left more than 4,000 paintings, 5,000 drawings, 66,000 photographs, 100 films, 4,000 hours of video, and 20,000 prints. The sheer magnitude of his oeuvre, combined with the varied and incomplete nature of much of his work, makes authenticating a Warhol an arduous task.

To an investor or a collector, though, it is a necessary one. Warhol prints and paintings have the dubious distinction of being among the most forged art in the world. Each of their characteristics—their rising value, their relatively cheap production, their simple style, their motley appearances, their wide-ranging provenance, and their high volume—make them conducive to forging and appealing to forgers.

Their value alone makes them an attractive target. Andy’s work has steadily appreciated since his death in 1987, with much of that value being realized in the past twenty years. In the early 2000’s, a single print from the Queen Elizabeth portfolio could be had for under $10,000; now, it would bring more than $500,000. A fake would only cost several hundred dollars to produce.

The way in which the prints were produced lends itself to forgery: screenprinting on paper or canvas is relatively easy, especially for someone who is already an artist; if someone can create a screen, they can make a template for churning out prints in the same way Andy and his team did.

Even the subject matter of the prints exacerbates the complicated nature of authentication. Warhol consistently appropriated images from magazines and newspapers. His Death and Disaster series was based on images pulled directly from the headlines—and occasionally the headlines themselves. As that source material is in the public domain, anyone can find it, match the colors and paint application technique, trace where the colors will go, and screenprint their own “Warhol.”

Most famous artists create only a few hundred paintings in their career, and each one is carefully recorded. While Andy’s works have since been catalogued, many were executed in large editions that were unsigned or not numbered. His prolificacy, unparalleled in the history of United States art, makes determining what is genuinely a Warhol more difficult—and creating an imitation Warhol easier.

But it’s that duplicability and prolificacy that is at the core of Andy’s art. He wanted to be a machine. Across every domain—style, source materials, production, volume—Warhol’s art was created to be replicated. Deeper than the canvas or paper itself, the ease and speed with which the image can be made, as if by a machine, is what makes a Warhol authentic.

The Warhol Authentication Board

In 1995, the Andy Warhol Foundation established the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board. The reason was two-fold: first, they needed to placate concerns that the Warhol market was beginning to drop in quality as prices rose; second, an internal inquiry found that Warhol’s former manager, Fred Hughes, had authenticated several ersatz Warhols. Without a clear, defined market, and confident buyers, the value of the foundation’s own holdings would drop.

"We decided that we wanted our money to go to artists and not lawyers."

The Andy Warhol Foundation

Over the years, the new board became so powerful that without its authentication, a piece of art simply did not exist in the Andy Warhol universe. With its authoritative stamp, however, a piece would be deemed forever a Warhol. Even so, the board struggled to consistently segregate real works from fakes. Several works it authenticated had to later be “reclassified” as posthumous works, according to a report from the board itself.

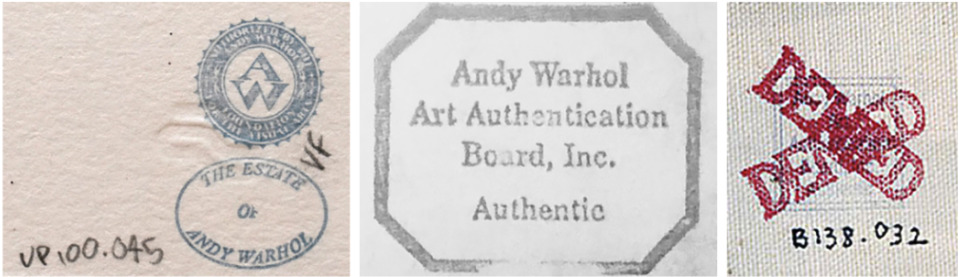

For example, an unsigned, unnumbered Marilyn print placed for sale by Sotheby’s in 2008 had three distinct marks on the reverse:

- A first “out of edition” mark, meaning the print was an original but had not been approved by Warhol.

- A second red x “denied” mark, added by the Warhol Authentication Board based on its decision not to authenticate works Warhol was not aware of.

- A third and final stamp indicating authentication—also from the Warhol Authentication Board.

In 2011, after evaluating about 6,000 pieces in its fifteen years of operations and following numerous lawsuits and controversial decisions, the Warhol Authentication Board was dissolved in order to concentrate its energy and funds on supporting emerging artists, as Andy intended.

Authentication Stamps

Using the Catalogue Raisonné for Authentication

Absent the Warhol Authentication Board, the most authoritative source for authentication is the Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné for Prints 1962–1987. The Catalogue Raisonné (“critical catalog”) lists every known Warhol print along with its characteristics, including the title, number of prints (if it is a portfolio), type of paper, physical size, edition size, number of artist proofs, number of printer’s proofs, number of trial proofs, signature type and location (if any), printer, and publisher.

Aside from the published works section, the catalogue remains incomplete. So, if a piece of art is not found in the catalogue, it does not necessarily indicate that it is a fake Warhol. If it is in the catalogue, the total edition number and the type of print should be matched with what is indicated on the print. Then, the entry can be used to verify the placement of Andy’s signature, the paper type, the dimensions of the print, and the date the print was created.

The catalogue, however can only be used to match in essence. There is no substitute for a print being examined in-person. Fortunately, the nuances of screenprinting—including the image, screens, color matching, paper matching, ink layering, embossment, and signature—make fakes relatively easy for an expert to spot. There are six primary factors used to aid in authentication:

- Signature

- Paper

- Aesthetics

- Provenance

- Embossments and Stamps

- Ink Layering

"I turned towards the idea of a rubber stamp signature because I wanted to get away from style. I feel an artist's signature is part of style, and I don't believe in style. I don't want my art to have a style"

Andy Warhol

Warhol's Signature Style

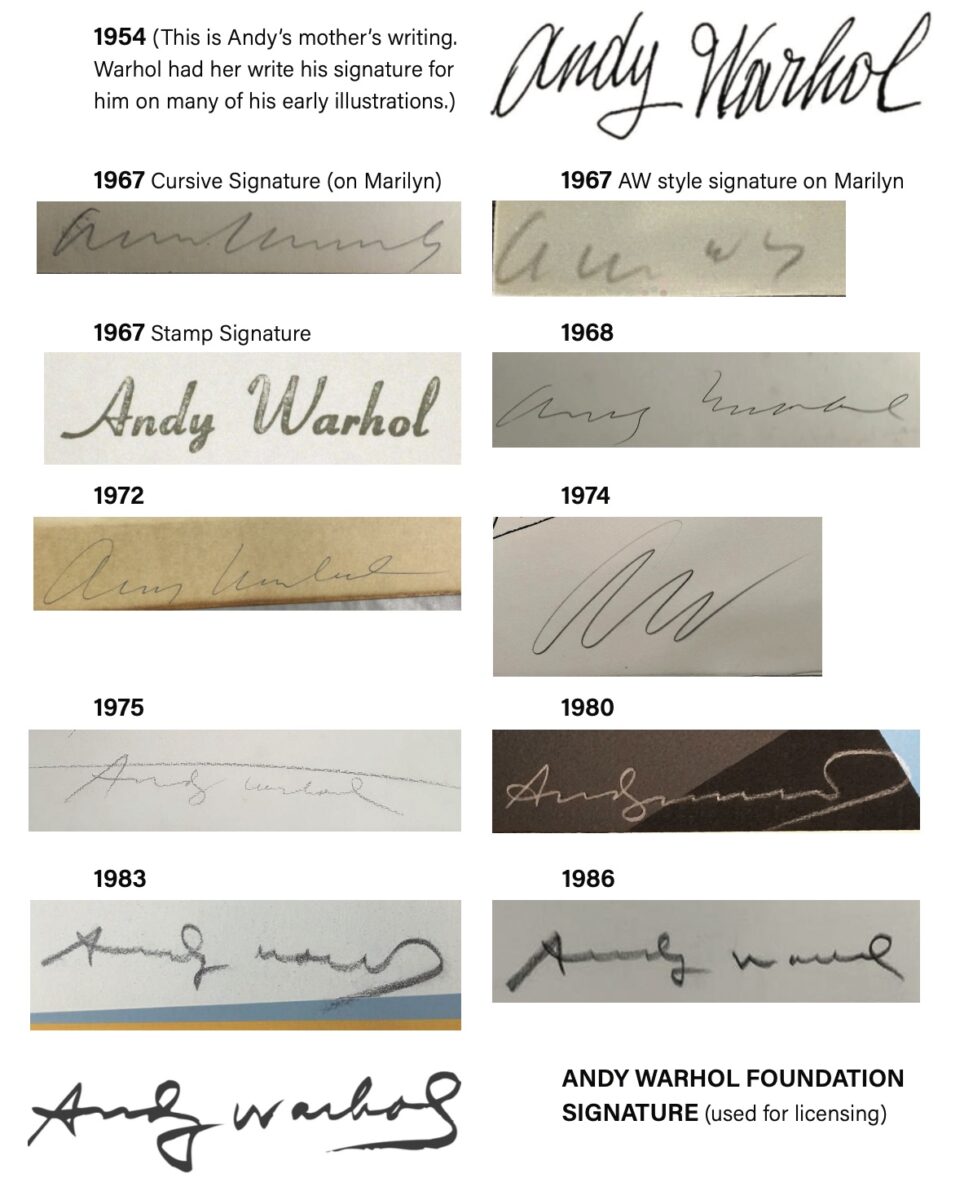

For prints or paintings that are signed, the signature can be an excellent determinant of authenticity. Unlike most artists, Warhol’s signature morphed several times over the decades of his career.

In 1954, he used a handwritten signature; by 1967, he was using a rubber stamp. By the ‘80s, his signature had progressed from cursive to a stamp to a scribble to a barely-legible scrawl. His final signature, used from approximately 1986 until his death, was Warhol’s most legible hand-written signature. Even in the consistency of his change, he was inconsistent: when using a rubber stamp, he would occasionally revert to a hand-written signature, and he signed some Marilyns “A.W.”, some “Andy Warhol” in cursive, and some “A. Warhol.”

The mere presence of a Warhol signature does not mean that it is a genuine Warhol. Screenprints are prone to fading. If the signature looks crisp or fresh, it could signify a forgery. Even a genuine signature might not indicate a bona fide Andy Warhol print. A statement from the Warhol Authentication Board made it clear that “the existence of the signature. . .does not mean that the picture is indeed by Warhol.”

QUESTION TO ASK: If the piece is signed, does the signature correspond to the documented signature Warhol used at that time?

Warhol's Signatures

The Human Touch

For all his bluster about wanting to be an artistic machine, Warhol’s editioned work was filled with idiosyncrasies and variations.

"I haven't been able to make every image clear and simple and the same as the first one."

Andy Warhol

The amount of ink squeegeed through the silkscreen resulted in unique prints each time—each with their own personality. The accent lines that transition from one color to another would change from print to print.

Andy did not regard his own work. He would make a mistake on a print, then sell it anyway. Forgers, in their attempt to copy exactly, will create prints that look too clean and perfect. While checking for accuracy in the print, also look for subtlety, complexity, and nuance, especially as it relates to other prints from the same edition.

QUESTION TO ASK: Does this piece look as if it were made mechanically, or does it have a human touch?

Premier Provenance

Art often comes accompanied by documentation, known as provenance, that confirms the chain of ownership since it was created. The provenance might also include authenticity, exhibition history, auction records, and conservation reports. Excellent provenance indicates a genuine work of art; no provenance indicates dubious genuineness.

Even here, Warhol unwittingly foils authentication attempts. He would often trade his art for services, including the printing itself. Assistants or friends would ask for a discarded canvas, and Andy would sign and give it to them. People who were in close contact with Warhol may claim to have a print directly from the artist himself—an unbeatable provenance. But if it is outside of the edition, it needs to have an estate stamp, authentication stamp, or a verifiable signature to be considered genuine.

A few provenance attributes can make it more desirable:

- Previous ownership by a highly reputable gallery

- Exhibition at a reputable museum

- Evidence of being auctioned through a well-known auction house

Each of these indicate that the art has likely been inspected by the expert eyes of fine art specialists and verified as genuine. Additionally, a certificate of authenticity or receipts from previous sales can add confidence in authenticity if there are any inconsistencies in other areas.

QUESTION TO ASK: Is the provenance in excellent order? Does it possibly indicate that previous owners conducted due diligence on the authenticity of the print?

Printer Paper

The Catalogue Raisonné lists the paper that each screenprint was made on. While it may not be possible for a collector to detect the type of paper, certain simple conclusions can be drawn. For example, Campbell’s Soup prints were printed on thin, inexpensive paper with a wax coating—a definitive artistic statement regarding mass production.

Aside from comparing the paper with a sample of the same paper, a visual inspection of most prints should also be checked for natural signs of aging, oxidization, and discoloration such as stains, foxing, or mold.

QUESTION TO ASK: Does the print appear too clean and new? Does the weight and texture of the paper comport with information in the Catalogue Raisonné?

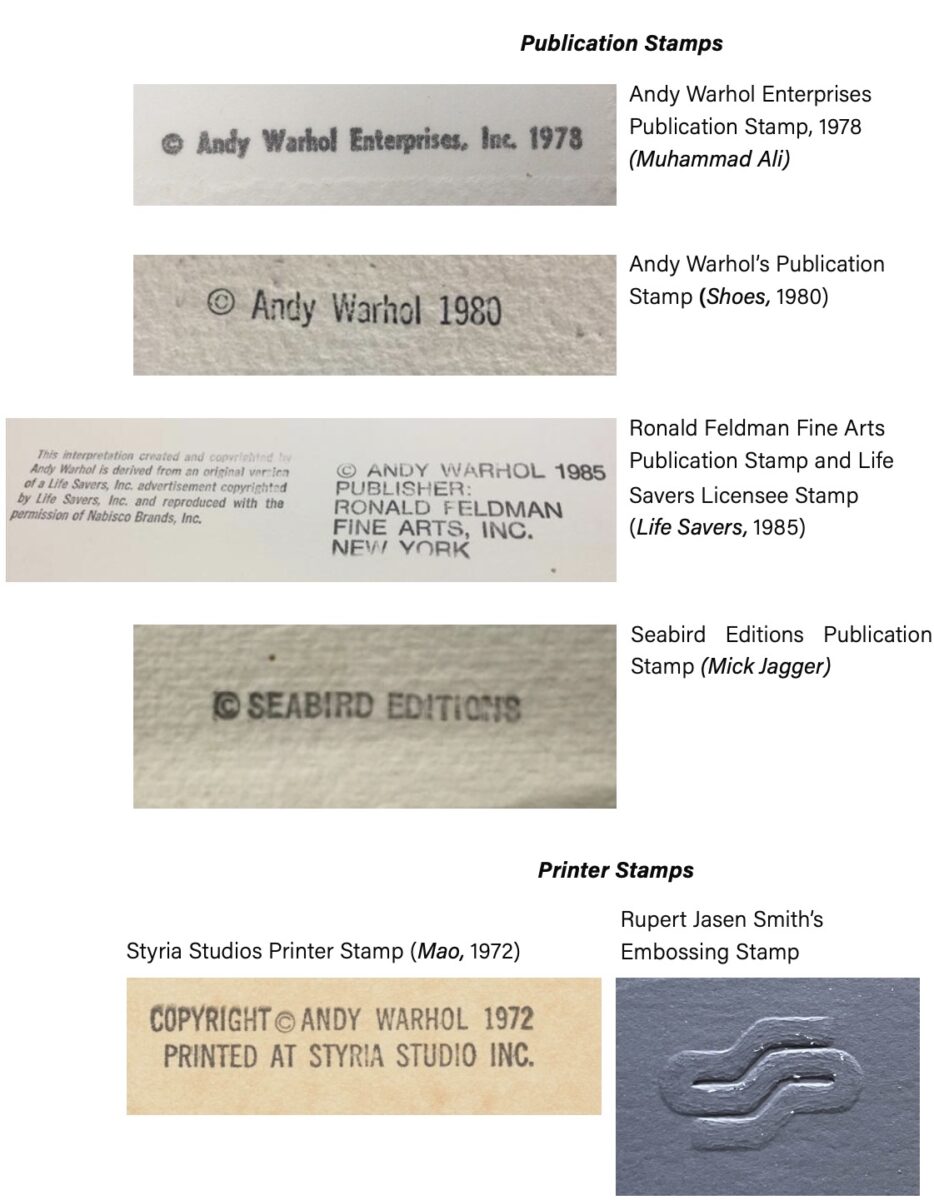

Embossments and Stamps

Publication and Printer Stamps

Embossments (“blind stamps”) were primarily used by printers and publishers of Warhol’s work. For example, works by Rupert Jasen Smith, Warhol’s “master printer” from 1977 until Warhol’s death, bear his “S” embossment. Embossments may also signify publishers such as Andy Warhol Enterprises, which used an embossed stamp of Warhol’s full name—as with Kiss.

Ink stamps were used by licensees and publishers of Warhol’s work. The Estate of Andy Warhol and The Andy Warhol Foundation have unique ink stamps used to certify the authenticity of a work. Walt Disney Productions, a licensee, stamped the back of Warhol’s Mickey Mouse prints.

Some printers did not stamp or emboss their name on the verso of any prints after publishing; for example, neither Alexander Heinrici (Mick Jagger, Ladies and Gentlemen) nor Aetna Silkscreen Products, Inc., (Marilyn, Flowers) stamped the back of Warhol prints.

Ink Layering

When creating prints, Warhol used multiple silkscreen layers. This means that there are no discrete boundaries between colors; rather, each color represents its own layer built on a base layer of a single color. Because of this, original Warhol prints exhibit a subtle third dimension—a unique layer for each color—that a forged print lacks. Observing the ink layers is key to authenticating a Warhol, but is difficult for the untrained eye.

Know your Gallery

Authenticating a Warhol print can appear to be a Byzantine, if impossible, process. The best ways to avoid buying a fake Warhol are to know the artist and his work, to examine the print itself, and to know the seller. Buying art from obscure auction sites rarely results in a bargain.

A gallery that deals heavily or exclusively in Andy’s work will provide the greatest assurance that the art is genuine. Their interest, like that of the Andy Warhol Foundation, is to keep authenticity at the core of buying art, keeping his work valuable for generations to come.