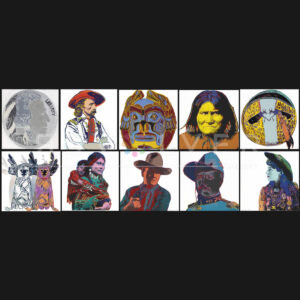

Kachina Dolls 381 by Andy Warhol is one of the ten screenprints featured in the Cowboys and Indians portfolio. Created in 1986, the portfolio explores popular images associated with the American Frontier. Warhol addresses themes and ideas of the Old West with screenprints depicting figures such as Annie Oakley, Teddy Roosevelt, Geronimo, General Custer, along with Native American motifs. Rather than portraying the subjects within their historical context, Warhol uses Pop Art to depict them as they are imagined: in an ahistorical and romanticized manner. Warhol effectively portrays the subject matter of the screenprints in the way Hollywood reconstructed them.

In Kachina Dolls 381, Warhol depicts the ceremonial dolls in Pop Art style, veering away from the realistic components of the objects. Kachina dolls are spiritual objects used in some Native American groups located primarily in the Southwestern part of the United States. The dolls are used by children, and act as a device for religious study. Additionally, the dolls are given to young women by their maternal uncles and used in coming-of-age rituals, such as the Home Dance (Kachina dolls are sometimes referred to as “home dancer dolls”) and the Bean Dance Ceremony. There are many different kinds of Kachinas, and it is difficult to identify precisely what each one represents. This is due to the differing interpretations of the kachina across geographical and cultural boundaries.

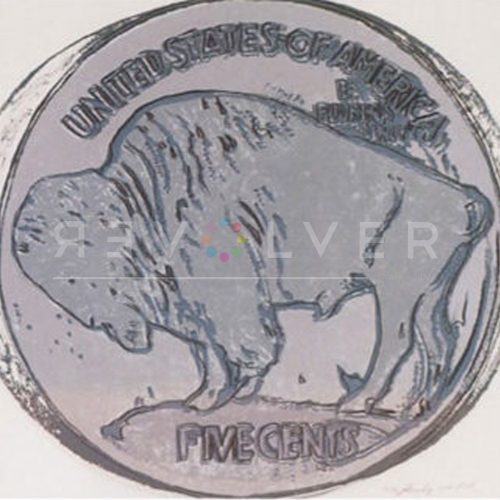

Though it is difficult to identify the dolls featured in Kachina Dolls 381, the screenprint presents them as objects representative of a generalized Native American culture. This screenprint, along with Indian Head Nickel 385, Plains Indian Shield 382, and Northwest Coast Mask 380, differ from others in the portfolio as they present cultural objects, rather than figures.

Though Warhol frequently regards his work and portfolios socially, politically, and emotionally neutral, the Cowboys and Indians portfolio is inherently charged with a major conflict in the history of Western civilization. The dichotomous subjects in Cowboys and Indians also presents each side in a manner similar to the portrayal of them in the media and common thought. Above all, through works like Kachina Dolls 381, Warhol reflects the generalized version of the Wild West, or, the way the American imagination has reconstructed its history, ultimately becoming more relevant than historical reality.

Photo credit: Kachina Doll Polaroid by Andy Warhol, 1985.